Weaver's Week 2021-07-11

(→In other news: ft) |

(→Michael Aspel) |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | Michael hosted film review show ''The Movies'' and interview show ''Personal Cinema'', talent competition [[Ace | + | Michael hosted film review show ''The Movies'' and interview show ''Personal Cinema'', talent competition [[Ace of Clubs]] in 1970, and proved his journalistic credentials on in-depth discussion programme ''An Hour With'' various showbiz veterans. But Michael was known mostly for one commitment. |

=== It's Friday, it's five o'clock === | === It's Friday, it's five o'clock === | ||

Current revision as of 12:17, 11 July 2021

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

The latest in our series of Living Legends, but who is the subject?

If only someone would give us a clue.

Contents |

Michael Aspel

Born in Battersea on 12 January 1933, Michael was the middle child of three – an older sister Pat, and younger brother Alan. His parents were Ted and Vi Aspel. All three were evacuated to Chard in Somerset at the start of the World War. Michael returned to London in 1944, and attended the Emanuel School. Blessed with a good singing voice, he took parts in the school opera. Michael completed his time in the army in the 1950s.

By now, Michael was living in Cardiff, at times he sold advertising space in the Western Mail newspaper, at times he worked in the David Morgan department store. Michael appeared in a number of Children's Hour drama productions, and as a reader of the Morning Story in the Light Programme, then joined the BBC as a staff announcer in 1957. "The BBC took me on because I could do accents." Welsh ones, West Country ones, posh ones.

Michael moved to London as a newsreader in 1960. "Bland and inoffensive", the requirements for BBC newsreaders, who weren't expected to be the star. The news is the star, Town and Around – the local news bulletin for London and the South East – its vehicle. The newsreaders shared a dinner jacket, and Michael had to use clothespegs to make it fit.

Almost inevitably, a newsreader will become a famous face, and take on other work. Might even get a suit of his own. Michael Aspel was no exception, he'd presented some editions of Come Dancing throughout his years in the newsroom. From 1966, radio came calling, and Michael took over the weekly Holiday Spin and Children's Favourites in the Light Programme, then Family Favourites on Radio 1 and Radio 2. He also presented Sixth Sense, a show where sixth-formers researched and gave a presentation on a topic of interest, and that was judged by a resident panel.

Michael was involved in a car accident in April 1968, and this was major news. His recovery was covered on television news, and the hospital received thousands of cards and hundreds of flowers. Shortly after, he left the BBC in 1968 to go freelance, and host The Monday Show. It's not a zillion miles away from The One Show, with Michael as the calm and unflappable host, and the actor Peter Jones playing the ebullient part of Gyles Brandreth. The Monday Show was part of a pair, David Jacobs hosted The Wednesday Show, a little more forward-thinking with a spot for someone new to television. The mixture of chatty interviews and mild pop music didn't catch the public mood, and the show came off air at the end of the year, replaced for 1969 by Quiz Bingo With A Perv.

Michael hosted film review show The Movies and interview show Personal Cinema, talent competition Ace of Clubs in 1970, and proved his journalistic credentials on in-depth discussion programme An Hour With various showbiz veterans. But Michael was known mostly for one commitment.

It's Friday, it's five o'clock

Michael had got his early breaks on plays in the radio Children's Hour, where he voiced the tall and dashing spy James "Rocky" Mountain of the FBI. Listeners were surprised to find that Rocky wasn't played by a larger-than-life hunk, but by this normal man who would blend into the background.

"Kids are such a critical audience," mused Michael before taking over Crackerjack. "There's a lot more slapstick in me than most people imagine." Michael was the third host of Crackerjack, from 1968 to 1974; it was part of the package he got with The Monday Show.

It's the era of Peter Glaze and Don McLean, of an ill-fated reboot in 1972 with Elaine Paige and Little and Large. Unlike his predecessor Leslie Crowther, unlike his successors Stu Francis and Sam & Mark, Michael Aspel was completely the straight man. All the comedy happened around him, he wasn't part of the stand-up routines.

And it's an era completely absent from the BBC archives: they haven't kept a single complete edition of Crackerjack from this era. We would like to draw conclusions between Michael, his predecessor Leslie Crowther, his successor Ed Stewart. But we can't. Sure, we can watch every edition of Panorama from this period, but nobody has ever wanted to watch Panorama even while it's going out. Cuh, eh.

Michael's time on Crackerjack came to a sticky end – he was pushed into a giant custard pie, 12 foot across, and had to be taken to hospital with wrist injuries.

Michael continued to to work on children's television, he hosted Ask Aspel, where viewers would write in and request clips to be repeated. This was in an age when nobody had videos at home, and an infinite box of television would be beyond anyone's wildest dreams. He'd also interview television's great, and the good, and quiz nemesis Basil Brush. Ask Aspel was accessible to children, without ever patronising the young viewer. The idea survived when Michael left in 1981, it became Take Two and continued into the 1990s.

"This is great telly"

Michael Aspel was also associated with the Miss World competition. Until very recently, the BBC and ITV thought it was entirely reasonable to show attractive young women on television, and attempt to judge who was the "most beautiful". These were glitzy and glamorous presentations, organised by the Mecca ballrooms and their charismatic head Eric Morley.

Every year, a different show, yet somehow all the same. Michael Aspel chats with the girls in a variety of languages, and cracking some jokes so weak they would qualify for Mr. Puniverse. The best names in showbiz would be invited along – Joe Loss and his Orchestra, Gary Miller sings, Lionel Blair taps, Bob Hope cracks jokes. The unchanging format – evening wear, national costume, deportment (as judged while wearing a swimsuit), before changing back into formal clothes for the personality round and ultimate crowning. And the winner always looks completely dazed and confused, gobsmacked that something like this could possibly happen to someone like her.

Clockwise from top left: Lionel Blair and his backing band; Bob Hope addressing the audience; Bob Hope looks confused; all of the competitors in national dress.

Clockwise from top left: Lionel Blair and his backing band; Bob Hope addressing the audience; Bob Hope looks confused; all of the competitors in national dress.

To modern eyes, Miss World and its ilk are an unwelcome throwback to a bygone age. The contest centres white femininity, judging all skin tones by standards set by a global minority. It also entrenches distinct gender roles, reinforcing the patriarchal ideas under critique then as now. Michael Aspel defended the competitors, correctly noting that "a good many were rather brighter than the journalists who annually put the show down as a cattle market". Feminist thinkers of the 1960s formed their own opinions, saw through the razmatazz, and reckoned Miss World was a perfect example of what's wrong with society.

Things came to a head in 1970, when members of the Women's Liberation Movement got tickets to the event. The protesters wanted to disrespect the event, not the women, so chose to wait until Hope was doing his "comedy" routine. Even by the standards of the time, he'd been outrageously sexist, beginning his interval act by saying how happy he was to be at "this cattle market tonight", and protesting that he wasn't a dirty old man. Rotten fruit and flour bombs flew at Bob Hope, as security bundled some of the protesters out of the hall.

Clockwise from top left: competitors travel to the Royal Albert Hall; protesters throw paper down; Michael Aspel and Bob Hope; three of the judges.

Clockwise from top left: competitors travel to the Royal Albert Hall; protesters throw paper down; Michael Aspel and Bob Hope; three of the judges.

The event featured on Radio 4's The Reunion in 2010. A television documentary – Beauty Queens and Bedlam – and a feature film – Misbehaviour – were released in 2020. The role of Michael Aspel was played by Charlie Anson.

Michael gave up the beauty pageants a few years later, fearing it was holding his career back. "When I took the job on in the first place, I played it for laughs. I got them, but now the joke has worn thin."

Michael did some stage work – pantomime in Croydon, a touring musical with Sondheim numbers, and straight acting in Lillie, where he met his third wife Liz. Michael kept his private life private, his four marriages were begun and ended without much press interest. He made a rare entry into political questions in 1971, supporting entry of The Four (Denmark, Ireland, Norway, and the UK) to the EEC.

Another co-signatory was Eric Morecambe. It's stretching it to say that "Michael Aspirin" was a regular on Morecambe and Wise, but he did make more appearances than most people: two, in fact. The last was in the spectacular "There is nothing like a dame" routine from 1978, where most of the BBC newsreaders turned triple somersaults and danced the salsa. When's Huw Edwards going to do that?

Michael with his Capital Radio colleague Kenny Everett. We'll talk about Michael's radio career next week.

Michael with his Capital Radio colleague Kenny Everett. We'll talk about Michael's radio career next week.

But if we might return to game shows. The News Game asked celebrities to guess the year from news items. The Movie Quiz was a panel game. He hosted two editions of A Song for Europe, and provided television commentary for two Eurovision Song Contest finals, in 1969 and 1976. The BBC entry won both times. Quest (1) was the BBC's first attempt at a phone-in quiz, from the team behind Mastermind. It was a broadcast pilot, an experiment, and demonstrated that experiments might not always work.

An experiment that did work: Star Games. Thames made its own version of the show for ITV, it was basically Superstars for television personalities. Michael, being cool and unflappable whatever happens, was the host for a show that was more entertaining and less competitive than the BBC show.

The shows had decent stars: one team included Avenger Gareth Hunt, Dave Prowse from Star Wars, Paul Darrow and Jacqueline Pearce from Blake's Seven, and Jenny Lee Wright from The Masterspy. Events included a canoe relay where Dave Prowse fell in, some motorcycling and some archery. There's a six-a-side football match, a running relay, and an obstacle course, because this is a show made for entertainment not sport. There are interviews with the team members, and everyone's raising money for charity – so expect short films about how the money will be used. The episode finishes with a tug o'war, which almost always determines the winner.

Top: Michael Aspel behind the shades, the obstacle course, the motorcross round.

Top: Michael Aspel behind the shades, the obstacle course, the motorcross round.

Middle: the tug o'war, the show logo, Dave Prowse prepares for the canoe round.

Bottom: competitor Ed Stewart, a running man, and Dave Prowse finishes the canoe round.

It's an entertaining programme, made with a wink in its eye. Michael's job as host is to link items together, do the interviews, and keep score. He makes it look easy.

Give us a Clue

Whenever we hear the theme for Give Us a Clue, we expect to see a sausage on a fork. The Thames television show used the same theme music as Grange Hill, the long-running drama set in a London school. But while the drama had Mr. Llewellyn, an affable but slightly ineffective headteacher who was often bested by his panel, Give Us a Clue has Michael Aspel, an affable but slightly ineffective chairman who was often bested by his pupils.

In Michael's case, there was a sensible reason: he was outnumbered eight-to-one. The team captains – Una Stubbs and Lionel Blair – would introduce stars of the time. Our sample 1980 episode features Libby Morris, Anita Harris, and Hilary Pritchard against Nicholas Parsons, Don MacLean, and Arthur English. The gender division is quite deliberate, Give Us a Clue was structured as "girls" versus "boys", a designation that hadn't been used at Arthur English for half a century.

The task is simple. Convey the entertainment on the card to your team-mates by the means of mime alone. An agreed set of "charades" signals is used, to denote the context (a film, a book, a play, a song), the number of words, plurals, and other conventions.

Una Stubbs might tell us that it's a book. It's got eight words. Eight words? Wow, long. First word. The. Fourth word, and Una collapses to the floor in a most theatrical style. Collapse. Plummet. Dive. Drop. Fall. Fall! The something something Fall. Sixth word, the. Seventh word, two syllables. First syllable, churning her arms and walking backwards. Rowing? Rowing! Row! Second syllable, and Una points to the opposite team. Men. Oh!

And that, folks, is how Una Stubbs told The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in less than two minutes. It's worth two points for her team. Had they got it within one minute, they'd have had an extra point. The other team get a guess if your team can't solve the charade in two minutes.

The game is very simple, there's lots of good-natured shouting, and the fun is contagious through the screen. Michael Aspel doesn't have to do very much – keep time and attempt to award reasonably accurate scores. He occasionally chose to gently remind contestants that they might not remember what's on the card correctly, it makes for better television. He also offered bonus points to ensure the match never ended in an embarrassing whitewash for either side.

Give Us a Clue had a long run, appearing from 1979 until 1991. There was some early weirdness, with a member of the public joining the celebrities on the panel. This idea was abandoned after the first series, though Win, Lose or Draw in the late 80s would show the power of that idea.

Michael Aspel had left Give Us a Clue long before then. He was replaced in 1984 by a no-nonsense Northern powerhouse, Mrs. McClusky, just as Grange Hill had the firm-but-fair Michael Parkinson in charge.

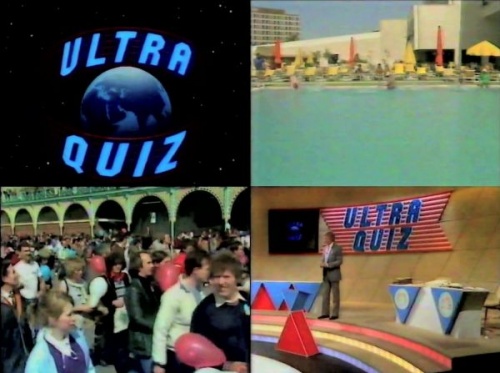

Ultra Quiz

Michael continued to work, and hosted ITV's big-budget high-concept show for summer 1983, Ultra Quiz. Two thousand people gather on Brighton beach, and were given this-or-that questions to answer. Only those who got the right answer could continue in the game. Once they were down to 200, the contestants took a ferry to France, from where only the top 50 continued on their journey around the world. The trip went to the Champagne region, then to Paris, Amsterdam, and Bahrain.

We join the show in Hong Kong, for the semi-final. Michael Aspel is in the very brown studio, with astrologer Russell Grant and computer boffin David Manuel. The contestants aren't safe in Hong Kong: they're joined by Sally James from Tiswas and Jonathan King from Top of the Pops. Eight against two, although only four will be flying back in the competition. The others will have to walk.

The flight from Bahrain was uneventful, apart from the questionnaire handed out by the Ultra Quiz researchers just before they landed. The first contestant descends the plane steps to the tarmac (this was in the days before they invented the skybridge) and Sally writes his score on his hat. The same charade continues for all eight players. Everyone else can see each other's score, but they can't see their own.

Who's got the lowest score? It's Richard, and he's got to go back up the plane steps and straight back to London.

The next two lowest scorers, Ray and Theresa, are going for a ride on the tram up Mount Toya. "One of them won't be coming back," threatens Michael, as though Sally will shove the loser into a 15-foot custard pie. Under the guise of a prediction, Russell Grant says a lot of words, very few of them make sense.

On the film, our players are asked questions by Jonathan King, with Sally James holding a microphone under the right person's nose (this was in the days before they invented microphone backpacks). In the final analysis, Theresa got two of her five questions right, Ray just got one, and he's off the show.

Six contestants remain, and they're taken to a floating restaurant for lunch. Lunch, and a questionnaire. They've been chased by these miniature exam papers all the way, and are filmed later talking about some of the answers they knew – and didn't know. Some of the captions are terrible, obscuring the contestant's face. Other captions are perfect, appearing right over Jonathan King's fizzog.

Who leaves? We cut back to Michael in the studio, and he'll tell us... after the break. Are you watching, Chris Tarrant? Spotting a good idea you can recycle as your own in fifteen years' time? Fair enough if he did. Anyway, the loser – Theresa – leaves the show, but not before she tries to catch a lobster in a freshwater pool.

From left: astrologer Russell Grant and computer boffin David Manuel; Sally James and Jonathan King at the airport; contestants Theresa and Richard flank Sally on the tram.

From left: astrologer Russell Grant and computer boffin David Manuel; Sally James and Jonathan King at the airport; contestants Theresa and Richard flank Sally on the tram.

The final round is held aboard a junk, and it's in three parts, beginning with a set of either-or questions. Then a set of questions to which Sally will read answers, and the contestant should signal when she's reached the right one. To prevent the players from copying each other, they're blindfolded.

Let's just pause to examine all of this. It's the semi-final of a big money quiz. We're on board a boat in Hong Kong harbour, and we've got a faded pop star and a custard-pie fan reading answers to a blindfolded group of contestants. This is absolutely bizarre, but the show is so po-faced that it doesn't even raise a single titter. Not a snigger. From four decades, we see echoes of (Wie is) De Mol, filming the most absurd situations as though they're the most commonplace event.

The round concludes with five questions to each player, drawn at random by pulling Mah Jong tiles from a bag. Lowest total score across the three rounds is out of the programme.

The graphics for the questions were clear, scores and marks appeared as needed. The ones in the studio, less clear.

The graphics for the questions were clear, scores and marks appeared as needed. The ones in the studio, less clear.

By modern standards, Ultra Quiz is efficient, it gets through the quizzing and eliminations in just over half an hour. We get to know something about all of the contestants, and we'd have found out more if we saw the whole series. But we only get to see Hong Kong by osmosis, out of the window of the tram or passing in the background of the boat. If they were going to make Ultra Quiz today, surely they'd let Sally and Jonathan out of their inquisitor mode and give us a little flavour of the city. They ask us all the questions about Hong Kong, but can they show us some of the place?

And, if they were making Ultra Quiz today, they'd do it entirely on location. No need for the filler with Mystic Russ or the Wong Computer. And no need for Michael Aspel to be in the studio.

We're going to leave the story of Michael Aspel here, and come back to it next week. We've seen how he's a safe pair of hands, a superb announcer, calm in a crisis. But what has he done to advance the world of game shows? We'll examine this question further next week, as Michael Aspel finds it's child's play.

Four Score

A few facts about Channel 4:

- Doesn't need any subsidy from taxpayers.

- Turned in a profit last year.

- Proves that top shows don't have to be expensive: Gogglebox is much cheaper than The Crown.

- Real people watch it, not just those poseurs with flicks on the net and their frothy coffees.

- Channel 4 News reaches 11% of the population every week, more than any individual print newspaper.

- Channel 4 News is more trusted than any news outlet other than BBC and ITV.

- Nobody knows where Channel 4's share certificate is, and nobody can prove who owns it.

Matt Deegan, the man behind Fun Kids Radio, notes

- C4 costs the public nothing, but by not being permitted to make programmes (or own the rights to them) it redistributes its billion pounds of advertising revenue each year to 400-odd companies, employing 20,000 people in the independent TV sector. At the same time its remit to provide challenging programming from unheard voices keeps it different from other channels and provides public value. It’s a very clever model – no public cost and plenty of public value.

- Any privatisation would re-direct a decent chunk of its ad money to shareholders and any new owner would want its remit revised so it could make more margin (probably by making its own programmes rather than use independent companies). It may generate a one-off £500m to £1bn for the treasury – but at what public cost?

Channel 4 also has a Global Format Fund, money to stimulate the creation of original new formats from indies within Channel 4's territory, for local and international audiences. Three products of that fund have been announced, and two are game. (The third, Open, is a documentary, exploring open relationships with some open-curious couples.)

Moneybags is coming to Channel 4 daytime. It's hosted by Craig Charles, and made by Youngest North. Contestants face a series of questions with the answers on bags of money that pass along a conveyor belt in front of them. Grab the right answer and you get that bag's value – anything from £1,000 to £100,000. Pick a wrong bag and you could lose everything. Every week a million quid will pass down the conveyor belt – it's up to the players to grab it. Six weeks of hour-long shows.

The Love Trap is for primetime. Joel Dommett is the host, Great Scott Media the production house. It's a format built around the last two minutes of Love Island, where someone is asked are they in it for love, or in it for money? Twelve women try to win the affection of one single man. But only half of the women want to win the singleton's heart, the other half want to win a big cash prize. At the end of each episode when one suspected love trap will be dumped, quite literally, through a trap door. Eight weeks of hour-long shows, which says to us "straight after Bake Off".

In other news

The death of Paul Koulak, the composer for Fort Boyard. Even before Who Wants to be a Millionaire revolutionised game show soundtracks over here, Fort Boyard was enhanced by its music. The atmospheric tunes enhanced each game, bringing out the fear or soundtracking the exertion, without ever overshadowing what the contestant was doing.

The death also of Jono Coleman; we'll have a fuller obituary in the near future.

The Weakest Link is back, with a new host. Romesh Ranganathan will host the celebrity shows, which we guess will air on BBC1 during the winter. A BBC press release quotes Romesh, "It's an honour to be asked to bring what is basically a TV institution back to our screens. Anne was an amazing host and to step into her shoes is an anxiety-inducing privilege. I'm hoping we've found a way to make both the fans of the show happy as well as bringing a new audience to it. If not, accept this as my apology."

Romesh is an interesting choice. We've described him in the past as a "fun sponge", grouchy and negative and sarcastic. All of these are qualities we can appreciate more on The Weakest Link than on a feelgood show like The Wheel. Celebrity editions give a license to be meaner – both in a pantomime style and because we can root with the celeb against the host. On the other hand, the Children in Need edition a few years back was just bad television, and the recent version on NBC and Channel 7 have completely broken the game. We live in hope.

Other shows have drawn their hosts from the BBC's Presenter Bran Tub. Bridge of Spies was first to dip in, and pulled out Ross Kemp. The Tournament drew Alex Scott, but will have to arm-wrestle Football Focus for her services. A Question of Sport drew out what was left: Paddy McGuinness as host. His resident captains will be Sam Quek and Ugo Monye.

Sportsball might come home tonight, but then it's going to stay in bed for a few days nursing its hangover. Instead, Quizzy Mondays make a return, and how! Radio 4's Brain of Brains kicks off a new series, there's new Pointless on BBC1, and Only Connect and University Challenge come back to BBC2.

ITV has Cooking With the Stars on Tuesday, and on Friday night, ITV2 tries to impress with Apocalypse Wow. Channel 4 has Can I Improve My Memory? on (when's it on?) Thursday.

Pictures: BBC, BBC / Mecca Organisation, Thames, Action Time / TVS.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.