Weaver's Week 2009-03-29

Revision as of 12:00, 22 December 2009

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

There's no doubt that some readers will not wish to read anything about Jade Goody. The vast majority of this edition is this column's take on her life, though there is some other news at the end. Normal service resumes next week, with a review of Raven: The Dragon's Eye.

"There's never a dull moment when I'm about."

Jade Cerisa Lorraine Goody was born in Bermondsey on 5 June 1981. She first crossed our radar, and that of six million other people, at about 9.30 on the night of 24 May 2002, when she was the ninth person to enter that year's Big Brother competition. She was loud, she was annoying, she only expected to last a few weeks. After seven days, it was no surprise that she was one of the two contestants atop the viewer poll to evict someone. If the remaining housemates had chosen to remove Jade, rather than Lynne Moncrieff, we would surely have never heard of her again.

Over the coming weeks, Jade learned to quieten down a little, did something (and we may never know what) with PJ Ellis, and – after drinking throughout a long hot afternoon – had a huge blazing row with Adele Roberts. Jade's tactic in this brawl would become her signature: she would attempt to shout louder and cry harder than her opponent, then apologise profusely later. At the end of week five, the contestants heard shouts of "Get Jade out" coming from the assembled crowd. Jade and Adele were amongst four contestants nominated for eviction the following week, and Jade was the early favourite to go.

In the three days that voting was open, something changed. We don't know what changed. It could have been Jade's behaviour in the house, which had already altered since she spent two hours talking with psychologist Brett Kahr the previous week. It could have been the editing of the Channel 4 nightly shows, or the suddenly good press she was receiving on Graham Norton's chatshow immediately afterwards, or the tabloid press taking sides like they do. Whatever it was, Adele left on almost a three-to-one majority, and the group's decision to have a nomination by lot assured Jade a place in the final, where she narrowly finished last.

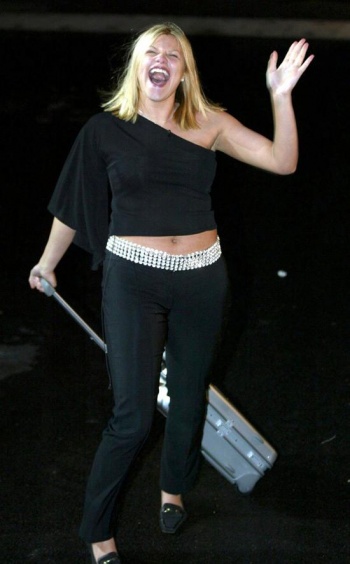

During Jade's time on Big Brother, the traits that had initially annoyed the audience morphed into quirks, shedding light on a quixotic character. She played the role of idiot savant, charming those viewers who did not want their heroes to be Mastermind material, merely the girl next door. It was never going to be enough: Jade's screeching voice and grating manner annoyed as many as it charmed, and such division meant she could not win Big Brother, not when Kate Lawler was a superior girl-next-door model.

Jade had already earned the grudging respect of the tabloid press, turning the headline of 12 July: "The most hated woman in Britain" to the following on 15 July: "We love Jade." She was all over the tabloid press, and the weekly celebrity magazines, for the rest of the year. Jade's first interview after leaving Big Brother was to Heat magazine, and helped to sell 650,000 copies; only Alex Sibley of the other finalists sold their story to a weekly. Big Brother in particular, and celebrity in general, suddenly became a raison d'etre for Heat, a magazine that had spent three years in search of a role.

For early Big Brother contestants, that was normal. What hadn't happened before was that the gossip rags remained interested for months afterwards. This column began to sense something unusual was happening when we were in a bookshop in North America in April 2003, and discussing the latest imported mags. "Who is Jade? What is she famous for?" asked our host. We could answer the first question, but the latter answer eluded us. It would continue to fox us for many years to come, and this piece – as much a biography as an obituary – attempts to discern the reasons for Jade's fame. We cannot honestly answer these questions without discussing her foibles alongside her achievements.

Jade (and it was always Jade, never Miss Goody) settled into a comfortable niche of post-modern reality television, appearing on Celebrity Wife Swap, Celebrity Driving School, Back to Reality, and the Big Brother Panto. Some suggested that her attitude in the last two productions could be seen as bullying. She released a number of fitness videos, the effects of which were only slightly undermined when it emerged she had had liposuction and plastic surgery.

Jade was prepared to meet the public half-way: she understood the value of humility; she took a course in basic literacy in order to read an autocue; and she was happy to laugh at herself and play to her public image as a bit dim and a bit silly. By the middle part of the decade, Jade had become the most visible face of Living TV, making Jade's Salon (about a salon she owned), Just Jade (about her perfume), and Jade's PA (finding a personal assistant). She also found time to promote an autobiography, and to run 80% of the London marathon. Her efforts raised over £500 for charity, a success on the scale of London Jam Week.

For most of us, a private life is just that – private. Not for Jade. She left Danny, her boyfriend of two years, when she went into the Big Brother set, romanced Jeff Brazier in public, bore two children, and split up, all in the glare of publicity. She briefly dated footballer Ryan Amoo, and subsequently took up with Jack Tweed, who served time in prison for assault. The couple were married in February 2009, with the declared intent of increasing Jade's legacy to her sons. All of this was played out in the pages of the weekly gossip magazines, and often on the front of the tabloid press.

Jade had stretched her fifteen minutes of fame into almost five years when she returned to Big Brother in January 2007. The celebrity edition was dying on its feet until she became embroiled in a huge row after making disparaging and racist remarks against fellow contestant Shilpa Shetty. Jade's perfume was pulled by retailers, she was dropped by an anti-bullying charity, and for a few weeks it looked as though she would be replaced in people's hearts by Miss Shetty.

Most celebrities would have gone to ground after such a humiliation. Jade spent a week in a celebrity rehab clinic, then bounced back. She went to India to apologise to a nation, and ensured that the moment was recorded for posterity by film and photo crews. She released a cookery book and accompanying video for amateur chefs, signed for another series on Living TV, agreed to do pantomime, and said she would appear in Big Brother's Indian series.

Her visit was short. Unbeknownst to most of us, Jade had had a medical examination in 1997, where pre-cancerous cells were found. Routine tests in summer 2008 found some abnormalities, and rather than seek early treatment, Jade went about her business as normal. She found out that she had ovarian cancer just two days after entering the Indian Big Brother studio. Though Jade had the best treatment possible, it would not prove sufficient to save her life. It was entirely in character that Jade would make television programmes about her illness, treatment, and demise.

Maybe now we might answer the question we were asked in 2003. What was Jade Goody famous for? Part of the attraction of Jade's story was the completely spontaneous plot. No-one had set out to pick a random person from an unfashionable part of London, make her fabulously rich, follow her around, and see what happens. It just happened that way, without any grand design, without any big debate.

For the press, Jade was a godsend. She was always good copy, and when Big Brother 4 failed to produce much tabloid fodder, Jade's fame became a self-fulfilling prophecy. She was famous because she was always in the papers, and she was always in the papers because she was famous. Like Diana Spencer twenty years earlier, what Jade lacked in formal education was more than made up in press favour. Her inexplicable success paved the way for such nonentities as Jordan and Kerry Katona, and it's salutory to note that all three have been handled by arch-publicist Max Clifford.

Whenever it was possible, Jade was portrayed as the underdog. She was always the favourite to lose Big Brother, never likely to pass her driving test, never set to last two weeks with Charles Ingram and his daughters, a ludicrous vision to attempt the marathon. Sometimes she succeeded, sometimes she failed. Her career was defined by a bunch of negatives – Jade was not the product of a two-parent family, Jade did not receive a good education, Jade bounced from failed relationship to failed relationship.

But Jade was also shown as the survivor. From "Jade the pig" to "Jade the fool", from insult to insult, criticism to criticism, Jade just kept doing what she did. We have no doubt that she was genuinely horrified that her off-the-cuff remarks were interpreted as racism when they were borne of ignorance; truly, she knew no better. Her reaction was to apologise, and to use the star power she had to make a grand gesture of her apology, to rival the grand offence she had caused. In her final weeks, Jade was credited for bringing attention to the risks of cervical cancer, and it appears more women than usual have had examinations.

Some have suggested that Jade's talent was to make other people feel smarter, prettier, better behaved. We don't particularly agree; for our money, Jade's supreme talent was, quite simply, to appear to be herself. While all about were following a script, Jade seemed to do what came instinctively. In the era of cynicism and spinning to the n-th degree, Jade appeared raw and natural.

Jade could sell magazines, but she needed them to sell. Her fame required her to keep a consistently high public profile; if there was ever a time when her star was eclipsed, she would be consigned to history. By April 2004, Jade was a millionaire. By March 2005, she was more recognised than politicians John Straw and Charles Kennedy. And as early as May 2003, she was number four in Channel 4's malevolent Worst Britons list. This didn't worry: all publicity is good publicity.

One commentator said this week that had Jade stood for elected office, she would have won. What caused people to flock round her, to treat her as a hero? It must have been her direct approach, the way she would call a spade a spade. But her bluntness was also a reflection on her times, when those who would claim to rule us are obsessed with presentation and appearance rather than actual policy.

And yet we find ourselves hedging our bets: Jade seemed this, Jade appeared that. The only times the British public had unmediated access to her were during her spells on reality shows – nine weeks on Big Brother in 2002, a week and a half on Back to Reality, the Big Brother Panto, and those twelve days in early 2007. During that time, she continued to play the child, and cause arguments for the sake of having arguments. For the remainder of her time in the public eye, Jade was carefully counselled by a phalanx of advisors, careful to ensure that she didn't let her mouth run too far away with her, didn't make any statement to give ammunition to people who doubted her talents. Her advisers ensured that she didn't let slip the truth, even if it was to her benefit.

Was Jade's success as much a product of her publicist as the woman herself? Jade knew she was a creation of the press, telling The Guardian in 2006, "I put myself in the limelight and I like my job. I know it's a circle and they build you up to knock you down, and I'm happy with that." Others were unsettled that she had been allowed to gain so much influence: while it is right to understand ignorance and intolerance, they argued that Jade revelled in these dubious and eradicable qualities.

From our point of view, Jade's defining characteristic was not that she had been damaged by her upbringing, but that she believed everyone else had been hurt like she had. She saw cynicism where none existed: Sophie Pritchard found her appearance on Big Brother in 2002 was gravely marred by Jade's bitching. Writing in Narinder Kaur's book in 2007, Sophie said that she had been accused of being "too nice" and "fake", and that she heard a chant of "fake, fake, [effin]' fake" as she left. Kate Lawler also found Jade to be "aggressive, rude, argumentative", and recalled how Jade had encouraged others to be nasty to Sophie, just as she would encourage Jo O'Meara and Danielle Lloyd to wind up Shilpa Shetty. The two eventually had a row in the penultimate week of transmission, Kate recalled that Jade had dragged up some slight from many weeks prior.

Maybe that was the key to Jade Goody's popularity: she attracted the broken, people who felt they had been let down by society. Jade stood for the victim, the dispossessed, the disenfranchised, the Little People. Many of her critics – and honesty compels this column to include itself amongst their ranks – were the people who benefitted from stable families, a good education, people who were literate and emotionally mature. Jade's constant presence was a thorn in some sides, a reminder that there is life beyond the leafy suburbs.

Even in death, the media didn't let Jade go quietly. From the start of February, she was almost never off the front pages of one or other tabloid newspaper and weekly gossip rag. Jade's publicists were forcing her into the eyeballs of the British public one last time, hoping they could turn her into the new princess of hearts. Was this emotional pornography? Was this a genuine outpouring of public grief? Could it have been both? For many people, the line was crossed on 17 March, when a pornography baron's gossip magazine said its 666th issue was an "official tribute" containing "Jade's last words". At this early date, the subject of the article was still alive, and obituaries were premature by four days.

It is difficult not to be moved by the human tragedy; once one strips away the trappings of fame, here is a young mother who has died of entirely treatable and preventable diseases. Flowers were left outside the Tweed family mansion in Essex, and a public funeral is planned for next week-end. There were tributes from friends, colleagues, and others hoping to steal a last little bit of the Jade magic for themselves.

International reaction ranged from bemusement to ignorance. The Globe and Mail in Toronto put Jade's picture on Monday's front page; Alex C commented, "I didn't know of her until the sad news of her passing," and Peter S wrote, "Why would this be news in Canada?" German ultra-tabloid Bild put the news at the top of its front page, under the headline "The shrill star fell asleep quietly". The BBC has been criticised for daring to lead its news bulletins with Jade's death for a few hours last Sunday morning, when it was new news and the largest news story on a slow morning.

We'll leave the final word to the unwitting architect of Jade Goody's eighty-two months in the spotlight. Phil Edgar-Jones, the producer of Big Brother in 2002, encapsulated her in a nutshell. "She proved that an ordinary person with no particular talent could connect with people." It wasn't what Jade did, so much as the way she did it.

This Week And Next

Nominations for the BAFTA Television Awards were announced this week. The game show nods went to Stephen Fry (QI) and jointly to Antan Dec (I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here!) in the Entertainment Performance category. Charlie Brooker's Dead Set got a nod in the Drama Serial award, while Features has The Apprentice and Celebrity Masterchef. QI and The X Factor received nods in the Entertainment category, with Numberwang paradoxically nominated in the Comedy award. Anyone would think they made it up as they went along.

Winner of the week was on The Sorcerer's Apprentice, which rather took us by surprise when it had its final last week, and not (as we expected) this week. All six finalists made a strong showing, and Elizabeth was given the top hat of success.

The main part of this week's OFCOM complaints report was taken up with criticism of television sponsorship bits. They're not meant to extol the virtues of the sponsor's product, but many – including those wrapped around Big Brother and The X Factor – were judged to have been at least a bit like adverts. Expect these sponsorship credits to become even more anodyne than before.

Ratings for the week to 15 March showed Dancing on Ice still in the lead with 9.65m. Comic Relief's Friday show led BBC1, followed by Thursday's Apprentice (8.55m) and Saturday's dancing final (8.25m). On Deal or No Deal, 2.55m saw a contestant win £250,000. Come Dine With Me repeats continued to lead in the multi-channel universe. Of greater interest is the decline in ITV2's game show ratings: Pop Idle Us attracted fewer than 400,000 viewers on Thursday night, and Paris Hilton is even less popular. UKTV Watch showed an old Apprentice Comic Relief special on Sunday, seen by 130,000.

It's the University Challenge Boat Race today (3.30, Eurosport 2 and ITV). Who Wants to be a Superhero? concludes on BBC2 at 9am on Saturday; the series is repeated on CBBC from Monday. Great British Menu also returns (BBC2, 6.30 weekdays) and there's a second series of Argumental (Dave, 9.40 Monday).

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers sign up to our Yahoo! Group.