Crisis Command

Contents |

Host

Gavin Hewitt

Co-hosts

Experts: Sir Tim Garden (military), Amanda Platell (communications), Charles Shoebridge (emergency services)

Broadcast

BBC Two, 3 February 2004 to 14 March 2005 (Pilot + 3 episodes in 1 series + 1 unaired)

Additional versions: BBC Four, 5 and 12 September 2004 (2 episodes in 1 series + 2 unaired)

Synopsis

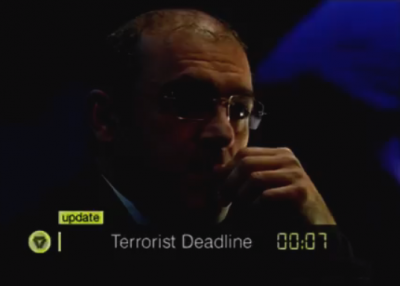

Three contestants, all of them successful in their fields, sit about a triangular table. They all pretend to be cabinet ministers in a government. Three experts are in the room with them: a military man, a spin-doctor, and an intelligence officer. Over the space of 3 hours, edited down to a 60-minute show, they get a series of crisis-management situations and tricky decisions that your average here-today-gone-tomorrow cabinet minister might take.

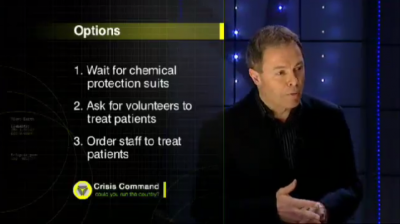

Our contestants must respond to the developing crisis by enacting one of the prescribed options, there are between two and four choices for each decision. They are told the results of their actions, and the decisions they take do have an effect on the later stages of the game. There is no officially declared victory or defeat result, but there is a summary of the effects of their decisions at the end of the show. The pilot episode concerned a mass terrorist attack on London; later episodes have looked at a flood and an outbreak of pneumonic plague.

Crisis Command was a very straightforward show, with an acknowledgement that every choice had its downside. With seven or eight decisions compressed into an hour's viewing, there was little time to explore alternate stories, or tell much of the pros and cons of other decisions. Some of the possible alternatives were explored in a further programme on BBC Four.

The contestants always have sufficient information available to point to the least-worst course of action, and this key information always arrives on time, perhaps a little too optimistic for reality. Some episodes are left rather hanging, with a crucial decision made, but no follow-up required.

The presentation is superb: real newscasters and accurate presentation graphics lent an air of realism. There are inconsistencies, mainly caused by channels rebranding their news coverage between filming and transmission. People walk across the camera shot from time to time - this does portray a busy bunker, and does help to remind us that we're watching a simulation, but there are times when this effect becomes distracting and slightly headache-inducing to the viewer.

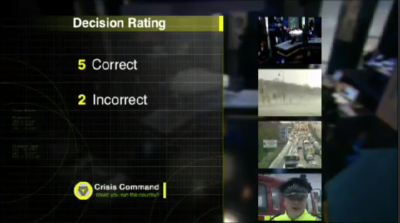

The BBC claims that Crisis Command is not a game show "because it has no prizes." We disagree; Crisis Command is a game show because it follows in the tradition of television role-playing. Knightmare it is not, but merely swapping the sword-and-sorcery idiom for a modern political arena doesn't alter a fundamental similarity between the two shows. The rudiments of a scoring system are present and correct - the programme gives the number of "correct" and "incorrect" answers, and sometimes details the cumulative damage to Great Britain PLC, or the death toll. It doesn't give any indication of the least amount of damage that could have been inflicted on GBPLC. Indeed, it's not immediately obvious that the least damaging course of action would be the recommended one.

To turn this into something even the BBC would call a game show, we might give the same outline script to two different teams, and rate their outcomes - perhaps by means of an Interactive Viewer Plebiscite, possibly by a studio audience, or even an Extremely Wise Man. The full series moved slightly in this direction, with the same scenario given to two teams in separate programmes, but with one shown on BBC Two and the other afterwards on BBC Four, and no direct comparisons made between them.

The teams have some latitude in their decisions, but the producers seem to have many dei ex machina at their disposal, to ensure that the show remains along the tracks they've planned and scripted.

The episodes are filmed, we assume, in real time, then edited down to broadcast. It would be possible to work the show to make events happen in real time, where an hour on screen took an hour in real life; this could lead to two-hour shows, too long for the regular weeknight - though as a weekend special, especially a live weekend special, it could be event television. Alternatively, the team could work on problems at a time warp, where one hour of screen time turns into a year, or even the four years of a parliament. That extended format allows one to, say, run the economy or the law and order strategy.

The pilot episode of Crisis Command aired in February 2004; on this strength, a short series of four scenarios were put together. Unfortunately, poor scheduling and the unfortunate timing of the events surrounding the real-life kidnapping of Kenneth Bigley meant that lost continuity, with the Hostage episode not aired until some months later (and with only one of the two filmed versions eventually appearing), and it's believed both versions of one episode was not broadcast at all. Shame, as in some ways this programme could have informed more than it distressed.

Still one of the BBC's most confident programmes in recent years, even if it hasn't been treated with the plaudits as well as it might.

Key moments

When Yo! Sushi bloke (and subsequent Dragons' Den participant) Simon Woodroffe caused the Houses of Parliament to be destroyed and was still defending his decision as the credits rolled. Stick to the sashimi, mate.

When one participant sought clarification about who was 'certain' to die in the dilemma presented, Sir Tim shot back with "One thing's for certain... we're all going to die."

Catchphrases

"Ministers, your decision will be enacted."

Inventor

Peter Burnell

Theme music

Philip Pope

Trivia

The show was originally piloted as The Bunker: Crisis Command - Could You Run The Country, shortened for the full series to Crisis Command: Could You Run The Country? and finally (for now) Could You Run The Country?. But mostly it's just known as Crisis Command.

One of the Ministers on the 'Flood' episode was Sayeeda Hussain-Warsi, later known as Baroness Warsi. The House of Lords member became a genuine Minister in three different roles in David Cameron's government.

See also

Weaver's Week review (8 May 2004)

Weaver's Week review (11 September 2004)