Weaver's Week 2019-07-07

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

"They say the family that plays together stays together," claimed Dara Ó Briain at the start of every episode. From that one epigram, we have so much to discuss.

Contents |

The Family Brain Games

Label1 for BBC2, 17 – 27 June

The saying was originally a little different. "The family that *prays* together stays together" was the slogan of the Roman Catholic Family Rosary Crusade, credited to advertising executive Al Scalpone in 1947. As is common with many advertising slogans, it became part of popular culture, often in slightly variant forms.

According to the faithful, the claim is that prayer strengthens bonds in families, and helps love to grow between the members of the family, and a loving family allows children (and parents) to find happiness and love in their lives. To the best of our knowledge, this chain of three assertions has never been tested in a rigorous study. Indeed, it is not clear how such a set of claims might be tested, and we might well deem the hypothesis to be unfalsifiable, non-scientific, and a matter of faith.

Family Brain Games is a rigorous experiment, there is scientific underpinning to each of the experiments here. There's no room for faith, because science will test the hypothesis that This Family is better than That Family at a specific arrangement of exercises.

And, note very carefully, all we test is this very specific format. This Family is better than That Family at the precise exercises on the show. We cannot generalise to say that This Family is better than That Family at anything else. This column has massive respect for all of the contestants, we were rooting for everyone in turn, and we sincerely hope everyone can look back on the recording with fondness.

Oh, get on with it

And if you think we're prattling on around the subject, it's nothing compared to the show. There was a very long piece where we saw Dara with Hannah Critchlow and her team of neuroscience experts from the LSE. We saw the families arrive, settle into their base for the day, and introduce themselves through short clips filmed at home. (And, through clips of the series to come, give enough spoilers to work out that at least one family would make the final.)

There is a fine line between "giving the teams their moment in the spotlight" and "being too slow to kick things off". It eventually emerged that Family Brain Games was a relaxed show, reflective and languid like butterflies around the millpond. We didn't know this at the beginning, and the eight minutes from opening credits until we first saw the teams meet Dara felt like an eternity.

As the name suggests, Family Brain Games was a family team game. It was played by teams of four, including two children aged under 18, and two older adults. The adults were usually mother and father to the children, but there were some other arrangements, including one with grandfather and father.

Those games in full

Letter Shift tests verbal reasoning and communication. Each player has one column of letters, and only they can see those letters. They can shift the letters up and down, so that reading across all four columns, a word is formed. The Voice of the Family Brain Games gives up to three clues to help form each word. It's a test of collective vocabulary, and of manipulating touch screens. Oh, and this is a timed event, most correct answers in three minutes wins.

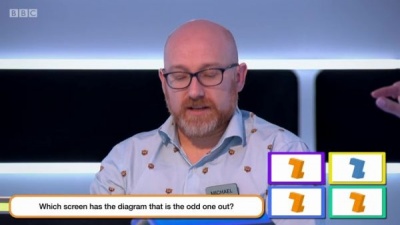

Colour Frame looked at 2d shape recognition and manipulation, logic, but mostly communication skills. One of the family is able to see a design. Their task is to explain it to the rest of the family, who are to build it using shapes on perspex slides. The person describing can't see what's being built, and the people building can't see the original. Success requires the ability to describe geometric shapes in detail, and the ability to listen and interpret the information received. Faster team to reconstruct the shape wins, and they're timed out after ten minutes.

Eight Things is a simple memory test. Here are eight things. They'll remain on screen until someone buzzes in, at which point they're to remember all eight. Fail, and the other player can complete the list and steal the point. This one's played head-to-head and in age bands, "younger members" don't play against grown-ups. More correct answers win, and according to Dr. Hannah, only 12% of people can remember as many as eight things.

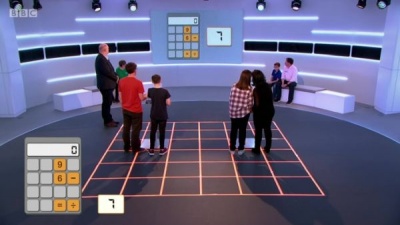

Broken Calculator is the maths game. Each team goes head-to-head in pairs. They see a calculator with most of its buttons missing. The challenge: how to reach the target figure using only the digits and symbols available. Again, more correct answers win.

The winner of each round – if there is a winner – earns 50 seconds for the final game.

Interrogation is the all-or-nothing finale. It's a test of logic, knowledge, lateral thinking, time management, communication, risk-taking, and knowing when to guess. Five questions are posed. The team cannot pass, and each player can only see their own screen. The players have to collectively work out the answer to the questions. There's a one-minute penalty for each incorrect answer, and the faster time overall wins.

Remember how each round earlier was worth 50 seconds? That's almost an incorrect answer here. Almost, but not quite.

Throughout the show, Hannah sprinkled insights from scientific research. We learn a little of how the brain works, what is happening, how that's different through age and experience. Where possible, Hannah's commentary was in context to what we're seeing on screen. It was all done through verbals, Hannah and Dara mention bits of the brain, but there's no effort to locate them or put them in context – oh for the visual brain from John Craven's Beat the Brain.

And we hear how proper scientific studies have looked at child development through their family. Family Brain Games is a mainstream entertainment on network television, it's difficult for them to give proper citations to reputable scientific papers. We think they may mean the longitudinal studies of closer.ac.uk, or papers in the reputable Journal of Child and Family Studies. None of these discuss prayer, of course.

Between the challenges, we have some short pieces filmed in the "green room", a suite of connected rooms. Each family has their own private area, and there's a shared lounge between. Plenty of soft seating, puzzles and activities, facilities for hot drinks and fruit. The teams can socialise if they wish, but if they want to sit quietly and meditate that's fine as well.

Round two

"Similar, but more difficult" the challenges for the second phase. The four heat winners take part in two contests, and the two fastest losers in the first round also return for a spot in the final.

Word Ladder was the word game. Players create a new word by changing one letter of the previous one. Everyone hears a clue, anyone can buzz in and give an answer. Once someone has answered correctly, they step back and leave the rest of that ladder to their team-mates. Anyone can say "pass" to move onto the next clue. One point for each clue solved, two bonus points for a completely-solved chain. This test of vocabulary turned to be best for the older members of the team, the strategy was to leave the easier words for the younger minds.

Shape Shifters was a 3d version of the shape building game. Here, the describer was to build a collection of cubes, using Tetris-like pieces in colours and shapes. The winners asked lots of questions while they were building, and were flexible in how they described it.

Pathfinder was a game for the adults. One was the token, the other a moveable wall. On a grid of squares, the players can move horizontally or vertically, but they can only stop when their path is blocked – by the edge, one of the filled-in squares, or the other player. The objective was to land the token on an indicated target square. It's a test of planning, logic, and spatial awareness.

Card Slide invited the younger players to do maths. Solve an equation, then slide the eight numbered tiles so as to get the answer to line up along the bottom of the screen. Mental arithmetic is tested for the equation, planning to get the tiles in the right place, and short-term memory to remember the answer.

The semi-final concluded with another round of Interrogation.

HUP!

The final round was always edited in a fashionable style. We saw it on The Button, we saw it on Time Commanders and Stephen Mulhern's In for a Penny. Two or more teams play the same task at different times, but they're edited together as if both are playing at the same time. It's the best arrangement for the viewer, we only have to concentrate on one question, and can play along at home.

But we have no idea about the time it takes. We cannot see if this family have retained their lead, or if the opponents have pulled back some time. The net effect is – generally – to build tension, but there's a distinct whiff of artifice. Some of the closer games could have benefited from a real-time edit, see the two teams go at each question, fading the sound up and down. This column understands what the producers have done, and why they've done it, but we're not convinced it's the best artistic judgement.

There's something interesting to say about the overall scores. Indulge us on a counter-factual, please. In one semi-final, the first four rounds were an absolute landslide for one family. Not just that they won all four, but they won all four comfortably. They bossed Chain Letters by 21-10, won Blockio by a minute and Target Finder by four mins, and beat Sum Shuffle 4-0. For these wins, the family get a 200 second head start. Their opponents proved excellent at Interrogation, and triumphed by 40 seconds.

Now suppose the format gave additional credit for big victories, and smaller credit for narrower victories. An 11-point win on Chain Letters might be worth 85 seconds, the wins on Blockio and Target Finder add 25 and 50 seconds, and Sum Shuffle a full 100 seconds. Suddenly, the defeat by 40 seconds has turned into a victory, and the series takes a different course. But would the leading family have been tempted to move more slowly than they did? Would the trailing family have taken more guesses? We'll never know.

To be clear, the producers were right to make the competition format they did. A flat 50 seconds per round is simple to explain, it doesn't make the programme any more complex than it needs to be. Indeed, a complicated scoring mechanic distracts from the show's focus: the brain, and the families, and the tests, in that order.

No, the scientific point is that the results are – at least in part – an artefact of the measurements. Heisenberg's uncertainty principle still applies: by measuring something, you're changing it.

The final

A little less game in the final, with three families to consider, profile, and catch up with. A fairly long recap at the start felt uncomfortably like filler.

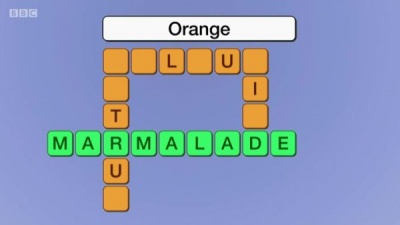

Cross Purposes was a crossword, all the words are linked by some sort of connection. First team to buzz in and give a correct answer got control of the puzzle, and were the only ones able to score points – one for each word, two bonus points for completing the puzzle with four words. It's a test of vocabulary, spelling, and language processing. For this column's money, the test was out of place in the final, being mostly a test of buzzer reaction. It also showed up the deficiency in the scoring system: the result was 10-9-4, for which the reward was 50-0-0. That feels unfair.

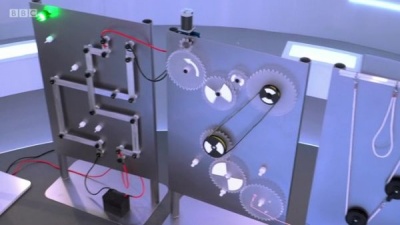

Chain Reaction tested mechanical and engineering intelligence, with a little spatial awareness and a chunk of logic. Each person was allocated one part of a mechanism, and only they could build it. While one person was building, all the others remained seated – they could advise, shout, talk, but couldn't stand up and take over. The four tasks were very different – arrange pieces to allow a ball to travel down, build a pulley system to bring a ball up, use cogs to operate the pulley system, and build an electrical circuit to turn the cogs. When it worked, it was spectacular.

Unlike in Interrogation (which followed), we saw each family take Chain Reaction in their own time. The This family took on the challenge, and solved it in their way. Then the That family took over, and used their brains to come up with a different solution. And then Theothers had their moment in the sun. Again, there was no clock on screen, we didn't know if the families had solved it quickly, or if they'd almost run out of time. Solving the puzzle was enough reward.

As we say, Interrogation eliminated one family, and the other two took part in the final round, Ultimate Brain Game. Questions on the buzzer, the families can confer. Buzz in and quickly give an answer, otherwise the opponents have a chance to steal. Five points wins the title; results from Interrogation are discarded, so a family excelling at the earlier format doesn't get an advantage in here.

The final also confirmed that the producers properly cared for the families. It's a high-pressure environment, people are going to be tense, there might be some snapping and some tears. There's a fine line to tread, the producers need to be truthful without being intrusive. At times, "tell, don't show" becomes the morally right thing to do. We reckon they got the tone absolutely right, and it helped to make the show a success.

Another winning move: Dara was very unambiguous in his support for the families. For example, one of the families had a difficult time with the shapes puzzle, and things were getting a bit stressed and a bit shouty before they fluked a solve. As soon as they hear it's right, Dara bounds through the door, beaming a big smile, and calling "Well done! Well done!" What was boiling up to a row was defused by the host's charm and bonhomie. Throughout the show, Dara gave praise for what people had achieved, and sympathy for what they had not.

We appreciated the set, coming at us from Future World. It's all bathed in eerie blue lighting, with a massive glass wall from where Dara and Hannah watch and explain. We really appreciated the music on the show – clearly audible in the narrative bits, and present but almost imperceptible during the challenges.

Our biggest criticism of the show is how an editing style doesn't always ring true, and how the host is one letter out in an interesting way. As criticisms go, these are piffling, puny, gravel on the highway. It's almost certainly in our Top Five shows of the year, and we'd love to see something similar next year.

Ultimately, Family Brain Games was a celebration of achievement. People weighing up the evidence, listening to other people's unique experiences, asking questions to help find the truth, and then acting decisively to declare the facts. We'd welcome any of these people as a leader.

Other people's work

With the annual summer slowdown almost upon us, and the beach beckoning, it's time to look around for other matters of interest. We might not be able to watch telly on the golden sands of Blackport, but we can hear podcasts and read short messages, and take printouts. Here are six things we're packing along with the bucket, spade, and snorkel.

Fingers on Buzzers is back! Jen Lyon and Lucy Porter's quiz podcast took an extended break, but returned a few weeks ago. The first two episodes of the resumption documented Lucy's turn on !mpossible Celebrities, which aired a few weeks ago. This week, an interview with Henry Kelly.

Retroquizzical is new from the podcast feeds. Paul and Les discuss classic game shows of the 1980s, and give ratings to determine a ranking. The show is mostly reminiscence, and the hosts aren't afraid to stick the boot in where they feel it necessary. We're particularly impressed with how the hosts have done their research, and draw some interesting conclusions of their own. As with all new podcasts, it takes a few episodes to settle into the format, so jump in with the episode on Treasure Hunt.

12 Points From America is another new podcast. Samantha Ross, Erik Nelson, and Danny Vopava talk all things Eurovision Song Contest from Minnesota. Two good jump-in points: episode 1 if you want to relive this year's contest, episode 5 if you're new to the contest and would rather answer "what is this Eurovision? Why are the Americans getting interested? Who are these people?".

Peake's Puzzle Page Puzzle master Daniel Peake sets a bunch of puzzles – wordplay and beyond, always with a bit of a twist. With one file every few weeks, we're talking high quality puzzles.

Eric Berlin's twitter puzzles Every day, the Merriam-Webster dictionary declares a "Word of the Day". Every day, puzzle author Eric Berlin makes a little puzzle out of it, and posts at @puzzlereric. From Wednesday, here's a step-by-step transition from "sedulous" to a very different phrase.

TV Years is another nostalgia product, this time a print magazine. It's written with style and wit, and a great deal of affection. The edition currently in shops is on Children's Television, running from Bagpuss to Why Don't You..? via a very nice item on Southern's Famous Five.

This Week and Next

The answers from the photos: STAR, 69 - 6 / 9 = 7, purple and green (check where the pole is), change the R to a D to make BADGE, 438 the target number, yellow, CITRUS, COLOUR, and RIND.

Good news for I'll Get This; BBC2's bill-splitting contest for celebrities will have a new series, starting with a festive special. We rather hope they'll see the 40-minute edits as the main feature, half-hour shows are so rushed.

Interesting news from RTL, where Love Island Nederlands has been renewed. The main show has been a success on RTL's Dutch-speaking channels, but September's second series will go out online only.

Radio 4's Brain hit semi-final 3. "East is east and west is west and ne'er the twain shall meet," a phrase for the opening round. David Stainer is the only player to get a starter question right, and takes a big lead. He knows that St Vitus is the patron saint of dancers, just don't tell Terpsichore. And he knows that Lester Piggott's first win was on a horse called "The Chase". Insert joke about your least favourite of the five here.

Richard Laurence pulls back quite a distance in round three, coming within an ace of a five-in-a-row, but he's ten years out with the Russian-Japanese war. Our host shows off by pronouncing the painter Molinaire's full name, in a round where the mononymed Dennis is the only to score; Colin Foster got his big points earlier. David Stainer comes within an ace of a Perfect Round – having grabbed all three bonuses, he zigs with "bridge" when Hoyle wrote the book on "whist". David's final winning margin is 21-15 over all the others put together.

BARB ratings in the week to 23 June.

- Coronation Street remains the most seen show (ITV, Mon, 7.3m). Love Island remains the top game (ITV2, Mon, 5.7m).

- The Voice Kids is next in line (ITV, Sat, 3.45m). Pointless takes advantage of ITV showing horse racing to move into third place (BBC1, Wed, 3.05m). The Saturday night light quizzes resolved in Stephen Mulhern's favour, Catchphrase (ITV) beat The Hit List (BBC1) by 2.55m to 2.45m.

- Family Brain Games began with 1.29m viewers (BBC2, Mon), and held near that level all week, except when it was up against England and Scotland in the football. Celebrity Crystal Maze came back (C4, Fri, 1.15m), and barely beat Taskmaster (Dave, Wed, 1.12m). Crystal Maze picked up 225,000 when repeated on E4 Sunday.

- Good score for Hey Tracey (ITV2, Mon, 635,000). Win Your Wish List came back (C5, Sun, 540,000). BBC4 had an excellent week, thanks to lots of live football, but found time for Cardiff Singer of the World final (Sun, 210,000).

- Disappointment for Master of Photography (Artsworld, Tue, 37,000), the up-itself arts contest barely beat charity baking contest Flour Power (BBC Scotland, Tue, 28,000).

The annual Wimbledon Exposition of Rainwear dominates schedules this week, to the extent that we don't have any new shows, or any finals.

Photo credits: Label1.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.