Weaver's Week 2015-11-01

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

A special edition of the Week, to mark the tenth birthday of Deal or No Deal.

Deal or No Deal (UK and India)

UK: Various Endemol companies for Channel 4, from 31 October 2005; commentary on "Sarah Millican Hijacks Deal or No Deal", 18 September 2015

India: &tv, from 5 September 2015; commentary on the edition of 13 September

The day of the tenth anniversary edition. Little Noely thought he was here because one of the players would have a second go, this time for charity. "No-one's done that before," said the host. Well, no-one apart from Olly Murs, winner of £10 in 2006, and 50p in 2011 when he was famous as The Nicest Man in Pop.

But the player isn't coming from the wings. The player, as plucked by "Pilgrim of the Day" (warm-up act Mark Olver wearing an interesting hat) — it's Little Noely himself! Sarah Millican steps forward from the wings, and treats Noel like he's treated 2000 other players over the years. Show some embarrassing pictures from his callow youth, and talk to an old friend in the studio. In this case, the "old friend" is The Banker, a mysterious figure who only ever talks down an old Bakelite telephone.

With the exception of summer breaks, Deal or No Deal in the UK has been running continuously since Hallowe'en 2005. It's mostly been a daytime programme, initially 45 minutes at 4.15, later an hour at 4. A weekend edition went out in early primetime, moving between Saturday and Sunday. There were a handful of civilian editions in primetime, and a short run of celebrity matches too.

The basic game has remained constant. Twenty-two different prizes are in 22 sealed red boxes. A top prize of £250,000, a bottom prize of 1p. Half the prizes are £1000 or more. The player has a box of their own, and will win the money contained in this box at the end of the game.

To establish their reward, the player calls for other people to open their boxes. What's in these boxes can't be in the player's box. After five boxes are opened, and then every three boxes, The Banker will call up and offer a sum of money to buy the box. The offer is a known amount, for a prize of mysterious value (but taken from the remaining options).

Will the player deal? Will they sell their box for the offered amount? Or will it be a no deal? Reject the offer, and play on for three more boxes. Whatever deal the player takes, or whatever's in their box, is what they'll win. The Dutch format has been sold internationally, with more success in some countries than others.

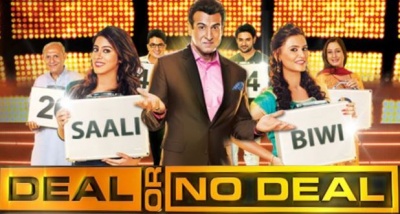

Over in India, Ronit Roy is the host. Or, to be precise, the fourth host. India had three series a decade ago, when Dealmania swept the world. Madhavan started the series, the show borrowed benches from the UK and sound cues from the Netherlands. It lasted 35 episodes.

Series two replaced the benches with briefcases, and introduced new host Mandira Bedi. She also left after three months, replaced by Rajeev Khandelwal, and the idea that future contestants hold the briefcases was also taken out – models now took them.

But Deal or No Deal didn't connect with the Indian audience. Perhaps it was the concept of winning something for nothing, perhaps it was the constant chopping and changing with the format. Perhaps it was that India prefers the intellectual stimulation of University Challenge and Just a Minute. DOND fell off Indian screens in July 2006, after just nine months on air.

Until now. The top prize is 10 million rupees (known locally as 1 crore). At market rates, a rupee exchanges for about one new penny, so the prize is about £100,000. By answering "how much can this buy me?" the value increases to about £400,000.

There are six prizes of more than 1 million rupees (£10,000 to currency traders; 10 lakh, in the local lingo), and the smallest box on the right-hand side is 100,000 rupees (£1000). Prizes go down – six are less than 1000 rupees, and the smallest available is one rupee (1p). Welcome to the one (ru)pee club.

But enough of the numbers, we're here for the people. The contestant walks on set, amongst 26 members of their extended family. Wife and husband, brother and sister, aunt and cousin, grandparent and grandchild. There's no lower age limit, children as young as ten might appear on the show.

Ronit introduces the selected player, and that player invites one of their family up to join them. The two have a fastest-finger-first question, putting three things in order. So yes, there's a chance that the player we've seen, the one we've spent ten minutes getting to know, is going to return to the stage.

The show is filmed in front of an audience of about 200 people, and it's good-natured. Apart, that is, from "Banker Babu". Everyone on stage wishes the player well, it's their mother, their son, their cousin.

Open the box. Low number! Brilliant! And there is singing. And there is dancing. Twice in the first round, play stops as one of the family gyrates about the stage. The steps flash, the host joins in, the audience cheers along. The camera pulls back to show two hundred people enjoying themselves, watching with smiles on their faces.

Watching with smiles on their faces. You don't get that in Bristol.

Noel took out two of the five biggest prizes in the first round, and grossly over-estimated The Banker's opening offer. Why is this important? During its decade on air, the UK game has accreted many traditions and catchphrases, many Byzantine rules, and a lot of games within the main game. They serve to keep the show's fans interested, but make it more difficult for new players to follow what's happening.

Once upon a time, each show began with the simple statement. "Twenty-two sealed boxes, and no questions. Except one: Deal, or No Deal?" Now, there's another question. "What's the opening offer from The Banker?"

Why is Noel writing down his prediction for this round? If he's sufficiently close (within 10% of The Banker's offer), Noel is able to force The Banker to make an offer – at Noel's convenience. But he's out, way out, and the offer button is just a dummy.

Five of the lower values go, followed by £1000, and suddenly Noel has a very strong board. At the half-way mark, The Banker offers £20,000 for the contents of Noel's box. He launches into a prepared spiel that makes absolutely no sense, and declines the offer.

Back in India, the game has turned. The player takes out gold after gold after gold. 20 lakhs. 50 lakhs. Even 3 lakhs is greeted with a jeer. The board is unbalanced, unstable. One bad round could see her playing for hundreds of pounds.

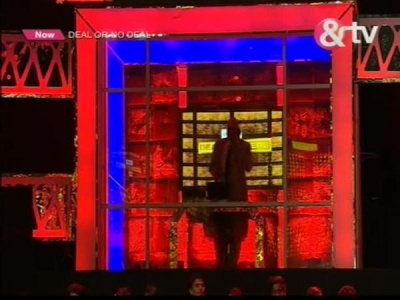

Banker Babu is watching all of this. His lair is a glass box, above the studio. We can see into his workshop, into his head. We can see his shadow stretch when the player takes out the big money.

The offers are sensible, reasonable, in this game always around 1,00,000 rupees. Enough to give the player something to think about, not enough to ask her to do something daft.

After each "no deal" decision, players whose cases have been opened leave the stage, and gather in a soft seating area.

In Bristol, Noel ploughs on. A low value, one below his last offer. And then Noel takes out the top prize. Will he take the offer of £15,000? In India, he might. In Bristol, no, no, a thousand times no. Noel plays on, and gets a final six entirely in the thousands. He's cheered by the players, standing at their benches even after they've removed their opened boxes.

Noel receives another confusing subgame plot: if he can predict the penultimate offer, with five boxes remaining, The Banker will raise the stakes for the endgame subgame (we'll get to the endgame subgame at the end of the game). But if he can't, The Banker will get to look inside Noel's box.

Noel is close, but not close enough: he under-estimates The Banker's generosity, so his box is whisked away for further analysis. Sarah Milican is doing a very good job as a substitute Noel Edmonds, she clearly knows how she wants the game to end, and that (in the grand scheme of things) the certainty of £26,000 isn't bad with three boxes in the low thousands, and two approaching six figures.

Ronit, our Indian host, has some hand signals. Deal (cheesy thumbs up) or No Deal (making a cross through the air). The studio audience have their opinions, and aren't afraid to voice them. There's social pressure to refuse early deals, but perhaps to accept later ones. People might be less likely to go for glory, they might accept their losses and take hundreds of pounds. Chase losses, and they might have a tenner.

Ronit also has a button. It's covered with clear perspex. Take the deal by pressing the button; reject it by closing the perspex lid.

Eventually, the player takes the fourth offer. Her husband and family gather to congratulate her, and Ronit signs off.

"But what about the prove-out," asks a British viewer. What prove-out? The deal has been made, let's get on with the next show. We don't see what was in the Indian player's case, or any other case. The game is over, the show does not go on.

In Bristol, a decision. Noel deals for £26,000. Twenty six thousand pounds for his charity. A great hour's work. Players applaud, and the credits roll.

Except they don't. After the deal comes Deal or No Deal: The Guilt Trip. "If we'd played on..." hypothecates Sarah Milican. This section is pure speculation, a fantasy for the viewer. Except it's not: this closing part is the instrument by which Deal or No Deal pushes its boundaries, controls expectations, tells its audience what to think.

Three boxes later, Noel is left with £3000 and £75,000 to be found. One is in his own box, one is in the last box on the wings. The Banker introduces another confusing subgame plot: the The Banker's Gamble. The offer is to repudiate the previous deal, and return to live play. Noel would take whatever's in one box, and he may – or may not! – have the chance to swap boxes.

Obviously, this can only happen in a format where they do do the prove-out. India could never have the The Banker's Gamble, because a deal is a deal, and an Indian would never repudiate a deal. These slippery Brits would.

If Noel had had the courage to play on... If he'd really wanted a lot of money... If, if, if. For the past ten years, Noel has been the surreal optimist. He's always pointed up the positives, the potential. He's never considered the negatives, never planned for a rainy day.

Deal or No Deal lost its audience for many reasons – it fell out of fashion, it became boring, it became hard work to watch, there were more compelling alternatives, Noel's borderline homophobia, Channel 4's staid daytime lineup meant it was an effort to watch. Surely one reason for its decline was this hypothetical element, almost every day Noel put forward a counter-factual argument.

Almost every day, he would pour guilt on contestants – a win of £26,000 feels like a defeat when you "could" have won £75,000. But this isn't real, The Banker's offers are inconsistent with live play, they are inflated to make players feel bad. That £26,000 in your pocket is real money; that £75,000 Noel talks about is evanescent, a number plucked out of nowhere.

And so it is here. Noel declines the The Banker's Gamble, chooses to swap his boxes, and reveals £75,000. Look at what you could have won. Never mind that you lost, you still won a bit, players applaud, credits roll.

Except they don't. Enter the latest confusing subgame plot: Box 23. The player can, if they wish, buy Box 23 with their winnings. This may modify their winnings: add £10,000, or do nothing. It could double, or halve, or cause a total wipeout.

By now, Noel looks completely bored and fed up. If he could be anywhere else in the world, he'd be there right now. He finds the whole charade tedious, banal, boring. So do we.

Deal or No Deal is a simple game, with a simple host. The Indian version makes a song and dance out of it, literally, and gives every opportunity for players to leave with something worthwhile. It gives every viewer a chance to have a smile on their face.

The British version is complex. In part, it's an exercise in probability. In part, an exercise in psychology, where The Banker tries to work out the cheapest amount that a player will accept in a given situation.

In part, it's expectation management, where Noel and The Banker use the show (especially the prove-out) to influence future behaviour. These characters exercise tremendous social control. They shape the studio to focus on the big prizes. They never pass up an opportunity to promote their values.

Noel encourages people to gamble, to chase the maximum amount. At every opportunity, he repudiates the idea that one can "settle" for a decent prize, he doesn't agree that there's any "satisfactory" amount of money. The show is built on avarice and greed.

And this asks difficult questions: was Deal or No Deal influencing people's approaches to money? Or was it reflecting the acquisitive era when it first reached UK screens? Deal or No Deal has become less popular for many reasons. Here's another: while society was changing around it, Deal or No Deal remained the same. It espouses the values of the credit-fuelled boom, the casino economy, of unearned gain, of not fixing the roof while the sun shines.

But when the mask is stripped, Noel reveals his colours. He'll settle for £26,000. Box 23 would have sent the money back – it had no effect. But if he's played the perfect game, Noel could have trebled that amount.

Finally, at the third opportunity, players applaud and credits roll.

Deal or No Deal has reached its tenth anniversary. We salute its achievements,

Normal service, with quizzes and viewing figures, resumes in next week's Week.

Photo credits: Remarkable Pictures (an Endemol company), &TV.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.