Breakaway

(→Series 2) |

(→Web links) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

== Web links == | == Web links == | ||

| - | [http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/ | + | [http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01nclv6 Official site] |

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breakaway_(game_show) Wikipedia entry] | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breakaway_(game_show) Wikipedia entry] | ||

Revision as of 04:59, 28 November 2012

Synopsis

Breakaway has a set of rules which manage to be simultaneously incredibly simple in principle and stupendously complicated in execution. Ok, so, here comes the simple version: 6 contestants mill about as a ‘team’ until one (or, normally, two) of them decides to go all-or-nothing to try to steal the entire prize pot.

Now for the details, and believe me, there are going to be a lot of details.

This show has 30 questions. 30 questions, 30 spaces on the track. See where this is going? OK, good.

The show starts with Nick Hancock saying some stuff, and then we’re off. No, wait, before we’re off there’s a 5 second countdown, during which the 6 contestants can buzz in (on remarkably modern hand-held wireless buzzers) if they want to go home with no money. Nick will offer them £1000 if they do this, but don’t listen, IT'S A TRAP, the money is actually for the other 5 contestants. And they’ll probably lose it anyway.

Fortunately today’s contestants know what they’re doing, so we’re off with question one. The first 21 questions are (very loosely) ‘themed’, grouped into 7 groups of 3, with the ‘category’ changing every 3 questions; the final 9 are pot luck (and for no real reason you get twice as long for those, 30 seconds as opposed to 15).

Now, despite the fact we’ve given them all buzzers to carry around, the way you actually answer a question on Breakaway is by stepping forward onto the next line – if you’re right, the studio flashes green and everyone steps forward to join you, if you’re wrong, you step back, which means, the game is actually over after 30 right answers, not 30 questions.

So the question comes up, a couple of people know it, there’s a short conflab among the team, made slightly awkward by the fact they’re having to stand in a line, a 15 second clock counts down, just to give Nick an excuse to shout if they’re all getting a bit tardy, someone steps forward, ‘ding’ and studio turns green, everyone steps forward, next question.

Nothing really happens for a while, and a good 60% of the questions on this show are really easy, with the other 40% falling into the ‘things you would expect someone else from a random sample of 6 people to know’.

Each correct answer under normal conditions gets £100 for the prize pot, but in the early stages this is almost completely irrelevant, because if you get one question wrong you go back down to zero, which will almost inevitably happen at around the halfway stage, and possibly again right before the end, rendering all the team’s hard work pointless. The only other thing to mention here is the slightly awkward situation this mechanic produces when the team are on £0, so there’s absolutely nothing riding on this question – if they’re wrong they’ll lose, um, nothing, and get to play the question again for the £100.

Now, every 3 questions we get to a break point, denoted by a flimsy red line on the set’s rather ITV-ish video floor. (High Stakes, The Cube.) Here, first, Nick asks an uncharacteristic, who/what/where question, and this time the contestants buzz in by actually buzzing in with their actual buzzers. A couple of people buzz in too soon, get it wrong, and then Nick gives them a really big hint and someone gets it. Green flash again. But no stepping forward.

Now, the person who got the question right gets a life, signified by a little blue dot on their name badge. (Which is possibly the cheapest cool way of keeping a tab on something we’ve seen for ages.) But, in an unnecessarily complicated plot twist, they have the choice to either “bring in a new life” or “take a life from (anyone else with a life)”. This effectively means if you get a life early-on you’ll probably lose it to someone else who gets a question later, which just adds to the ‘early stages being completely irrelevant’ theme. Or so you would think. Actually, for the most part the contestants have tended to play boringly fair.

Next, in another unnecessarily complicated tactical twist, the life-winner gets to pick the next category – from a board of seven, which will all get used (so all they’re actually doing is choosing the order).

Now, Nick will remind us, those lives are only actually useful to you if you breakaway, so does anyone want to breakaway? Another 5 second countdown ensues (at least it’s only 5 seconds – we bet there was a temptation to go for the Poker Face-style 10.) But no-one does, and who can blame them, it’s way too early. This whole cycle repeats a few times, with different people getting and stealing lives, and the group pot sneaking up and then periodically crashing down when they mess up or get a stinker question.

After the 6th break point (including the one at question, er, zero), for no real reason, they stop playing for lives. So now break points are just about breaking away. And good, because it’s about this time someone who’s got a couple of lives will fancy their chances and take a pop at it.

A note here for future breakaway contestants: in 90% of shows, someone will breakaway too early and leave with nothing.

Now, after an unnecessary lot of flashing lights and noise, Nick will invite them over to the breakaway side of the track (which is red!) and explain that now they’ve broken away, every question adds £300 to the prize fund (which is now also red!), and so because the ‘get it wrong and you have to go again’ rule, we know exactly how much the breaker-awayer could win if they make it all the way. (And Nick will remind us of this figure, often.)

However, in another tactical twist, they get the chance to ask one other person from the pack to help them (but they don’t have to), and if the person who gets asked agrees, they both take on the next questions. If the person who gets asked doesn’t, that’s it, they can’t ask anyone else until they’ve made it to another break point.

Now, over on the breakaway side of the track (which is red, in case you hadn’t realised,) the rules are slightly different, a correct answer is worth £300, and a wrong answer loses you a life, or means you have to do the walk of shame to the back of the studio (where there doesn’t seem to be a door, which makes it just seem obviously a rip-off of Weakest Link, as opposed to the impossible theoretical £10k top prize, host catch-phrases, team/individual play game mechanic, heavy lighting and 45 minute daytime slot on BBC2, which are all just co-incidentally rip-offs of Weakest Link).

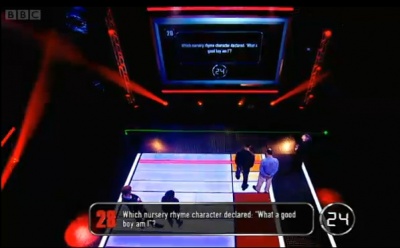

A question in progress. This is a rare instance of the studio screen being visible to the viewer during a question - usually this angle is only used to display the prize money.

A question in progress. This is a rare instance of the studio screen being visible to the viewer during a question - usually this angle is only used to display the prize money.But wait, there’s another unnecessarily complicated tactical twist. If you’re on a team of two breakers and you get something wrong then, in a display of rather cruel television, the remaining players have to choose who should lose a life/go home, which in practice means it’s always either the player with the fewer lives, or, who has shown the better general knowledge.

Note also, that any breaker on their own can ask one, and only one, person for help whenever they reach a break point – even if they’ve already had one or more partner(s) eliminated.

Now, should the breaker or breakers fail, then the team resume play again but from the same point the breaker was upto, and with the same money the breaker was up to. Normally this means the team ends up with a rather better pot (say, £3-5k) than they could have hoped for, when the breaker messes up. This will sometimes cause one of them to breakaway again, but in other cases they decide to agree to take the final questions together, which is dangerous because: 1- an incorrect answer still looses them all the money, and 2- prisoner’s dilemma. (And just to compound the potential for betrayal, there’s an extra break point between Q29 and Q30.)

If the team finish all together (rarely happens) they all split the money evens; if a breaker finishes alone, they take the whole lot.

The last thing to be mentioned is the fact that if two breakees make it to the finish, they split the money 50:50. This is a nice departure from the obvious potential prisoner’s dilemma, but does create the seemingly unnoticed opportunity for the player with more lives to deliberately throw the last question as many times as necessary for his partner to get eliminated, and then play for the entire jackpot alone. We’ve never seen this openly happen (though we've suspected it once or twice), but there doesn’t seem to be anything in place to stop it. In fact, Nick has even suggested the possibility himself.

So that’s Breakaway. A nice little game, even if it takes a couple of viewings to get used to the rules. And the ‘lose everything for 1 wrong answer’ mechanic seems to be quite harsh on the team, and makes most of the early game just dreary.

Series 2

A few changes are in place for series 2: an animated title sequence (the first series just had shots of the set), new graphics (neither better nor worse than the old ones, just different) and some alterations to the gameplay. It's shortened from 30 to 25 questions, six categories rather than seven and four lives rather than five. The questions on the breakaway track are now worth £400 each, so that the maximum pot is still ten grand. Also, a life can now be used to save the prize fund on the main track. Given that the 30 question format never felt that rushed, the decision to cut it down to 25 is rather strange and leads to some awkward padding. Basically with a no-frills, no-studio-audience show like this, we'd like more quiz, not less.

Catchphrases

"Does anyone want to breakaway?"

"Who, what or where is this .."

"Join us next time, when six more players must decide between safety in numbers or standing out from the crowd. Goodbye"

Theme music

The theme music was composed by Marc Sylvan and the music used in the show by Paul Farrer.

Web links

Videos

The very first episode.