Weaver's Week 2023-05-28

(Created page with 'Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week As he prepares to retire from professional broadcasting, …') |

m (→"That big rubbery horse-face of mock incredulity" – Malcolm Tucker) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | Paxman gave himself a freedom denied to his predecessors: to question the elevated position politicians want to occupy. "Why are our politicians so crap?" would often be the subtext of his opening remark, as it was the title of a documentary he made in 2019. Sometimes, the text would be like Matt Bianco on ''Saturday Superstore'', as junior minister Chloe Smith found to her cost. "You can't even tell me when you were told what the change of policy was. You were told some time today clearly, was it before | + | Paxman gave himself a freedom denied to his predecessors: to question the elevated position politicians want to occupy. "Why are our politicians so crap?" would often be the subtext of his opening remark, as it was the title of a documentary he made in 2019. Sometimes, the text would be like Matt Bianco on ''Saturday Superstore'', as junior minister Chloe Smith found to her cost. "You can't even tell me when you were told what the change of policy was. You were told some time today clearly, was it before or after lunch?" |

When Paxman dies, the clip they've got on standby is of his 1997 interview with Michael Howard. Paxman was interested in the removal of a prison governor by the Prison Inspectorate after some prisoners escaped, and whether Howard had *told* a reluctant Inspectorate to fire the governor or merely *recommended* it. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" asked Paxman. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" he repeated. Twelve times, in total. On each repetition, Michael Howard gave a slightly different response to the question, never quite answering it. And so the pantomime went on, Michael Howard answering the question he wanted to be asked, Jeremy Paxman asking the question he wanted answered. This interview helped to cost Michael Howard the Conservative party leadership. | When Paxman dies, the clip they've got on standby is of his 1997 interview with Michael Howard. Paxman was interested in the removal of a prison governor by the Prison Inspectorate after some prisoners escaped, and whether Howard had *told* a reluctant Inspectorate to fire the governor or merely *recommended* it. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" asked Paxman. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" he repeated. Twelve times, in total. On each repetition, Michael Howard gave a slightly different response to the question, never quite answering it. And so the pantomime went on, Michael Howard answering the question he wanted to be asked, Jeremy Paxman asking the question he wanted answered. This interview helped to cost Michael Howard the Conservative party leadership. | ||

Revision as of 10:27, 28 May 2023

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

As he prepares to retire from professional broadcasting, let's give a tribute to the second host of University Challenge,

Contents |

Jeremy Paxman

Question One!

"I was astonishingly lucky," says Jeremy Paxman in the foreword to his autobiography A Life in Questions. There's a grain of truth in Paxman's self-effacing modesty; there's also a grain of Paxman seizing every opportunity and putting his all into it.

Jeremy Dickson Paxman was born on 11 May 1950, the child of Keith and Joan Paxman. Keith was a merchant seaman, frequently away from home; it was during one of his trips that Joan moved with her family in Leeds to care for her first child; two other sons and a daughter followed in the subsequent years. Although Jeremy was born in Yorkshire, the family lived near Fareham in Hampshire, where many of his mother's relatives lived.

The clan moved in 1957, after Keith Paxman got a job at a steel works near Bromsgrove. Their new home was at Lickey End, a village with a mildly smutty name to outsiders. The Paxmans were "precariously middle-class", according to Jeremy, and scrimped and saved as much as they could. The one luxury was to educate the children at private schools, such as the small one just over the hill.

Young Paxman doesn't recall his time at Lickey Preparatory School with fondness. It sounds like a right ramshackle affair, with an "eccentric" headmaster, teachers who may not have known much about their subjects, and parents who were encouraged to pay their bills and stay away. To nobody's surprise, the school closed shortly after the Paxman boys had graduated. (The building still stands; this column paid a visit earlier in the year, and saw a small Victorian manor turned into a conference centre, with modern bedrooms and meeting rooms, with a couple of large halls on site. We also passed by Paxman's childhood home, which appears to still be a private residence.)

Lickey Hills Prep. One of the buildings where young Paxman might have received something approximating an education.

Lickey Hills Prep. One of the buildings where young Paxman might have received something approximating an education.

Jeremy Paxman was sent to Malvern College to further his education. He hated the place, describing it as "churning out District Officers in the fast-vanishing Empire". Not being the sporty type, he tried boxing, and was reeling for a week. He took up smoking, drinking, and assignations with local girls, and managed to get thrown out of the school twice. The headmaster's notes were uncomplimentary: "neither stable nor industrious... his enthusiasms are short-lived … very bad at working when he does not feel emotionally involved with the subject of his study".

But that didn't stop Jeremy from going to Cambridge University via a kibbutz near the Sea of Galilee. The utopian ideal of a society built on merit and sharing equally didn't ring true for him, but neither did the kibbutz. At Cambridge, he attended precisely one meeting of the university Labour club before giving it up as too dull; and one meeting of the debate society before tiring of the upwardly-mobile witterers. The university newspaper Varsity was more his scene, and after writing most of the copy, young Paxman edited the publication for a year. He graduated from St Catharine's in 1972 with a BA in English.

St Catharine's. One of the buildings where young Paxman might have received something approximating an education.

St Catharine's. One of the buildings where young Paxman might have received something approximating an education.

Taken on by the BBC as a trainee journalist, Paxman was tested as a sub-editor in the radio newsroom – the sort of person who will take in a ten page communiqué from Pottsylvania and summarise it in two sentences. Someone else will then read it out, and the magic of short wave radio will inform the good people of Pottsylvania what their government said, often before their government bothers to tell the good people of Pottsylvania.

Working first in Brighton, and then in Belfast, Paxman was exposed to the rigours and banalities of a journalist's life. The daily call to ask the fire brigade if anything had happened. The days scribbling down shorthand in court. Interviews with lady cobblers, and following John DeLorean's fantastic plan to build futuristic cars, and getting put on a hit list after an interview with Gerry Adams led to the Sinn Féin leader appearing in court. All in a day's work.

Paxman moved from Northern Ireland to less troubled parts of the world, picking up a reputation as the guy who will go to any war zone. The death squads of El Salvador, the ethnic cleansing and despair of Yugoslavia, all were grist to his mill.

Although Jeremy Paxman has a reputation for crepuscular television, his first regular desk job was on the regional programme London Plus, then a few years on Breakfast Time. It was the late 80s, all starchy suits and a "hard news" programme that might have been good for you, but nobody would watch when Anne Diamond and Nick Owen and Timmy Mallett were on the other side. Like most of his guests, Paxman was tired from getting up at 3am, hungry from not having had a proper breakfast, and grouchy.

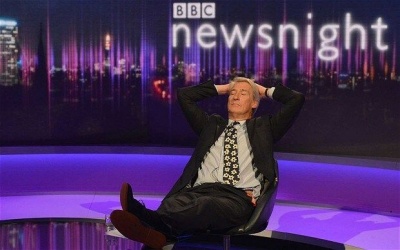

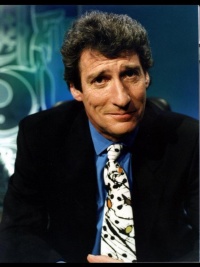

But it's Newsnight that was Jeremy Paxman's big gig. And it's Newsnight that he'll be remembered for.

"That big rubbery horse-face of mock incredulity" – Malcolm Tucker

The political interview on television has gone through three distinct phases. In the 1950s, when television was new, questions were typically "Is there anything else you'd like to say, minister?" – a feed to the politician to put his case without challenge. Some modern-day politicos wallow in nostalgia for these days.

A more aggressive interview was pioneered by Robin Day in the 1950s and 1960s; he would listen to the response, and actually ask a follow-up question based on what he'd heard. Although he'd twice stood for the Commons, Day thought of himself as an outsider looking into the glasshouse of politics, hoping to ask what a well-informed viewer would ask. His style brought both light and shadow; it allowed us to see the quick wits of Harold Wilson, hear Lord Jellicoe making himself look like a fool, and ruthlessly expose the vacuum behind Enoch Powell's faux-intellectual posing.

Robin Day's style was refined in the 1980s and 1990s, by heavyweights like Peter Sissons, Peter Snow, and the Dimbleby brothers David and Jonathan. All positioned themselves as outsiders; many would have liked to have been politicians in their own right. Jeremy Paxman represented a new breed of interviewer, because he didn't want to be elected. He wrote later, "the reporter is there to speak for the governed, and a journalist who has spent all their working life in the company of politicians loses that perspective".

Paxman gave himself a freedom denied to his predecessors: to question the elevated position politicians want to occupy. "Why are our politicians so crap?" would often be the subtext of his opening remark, as it was the title of a documentary he made in 2019. Sometimes, the text would be like Matt Bianco on Saturday Superstore, as junior minister Chloe Smith found to her cost. "You can't even tell me when you were told what the change of policy was. You were told some time today clearly, was it before or after lunch?"

When Paxman dies, the clip they've got on standby is of his 1997 interview with Michael Howard. Paxman was interested in the removal of a prison governor by the Prison Inspectorate after some prisoners escaped, and whether Howard had *told* a reluctant Inspectorate to fire the governor or merely *recommended* it. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" asked Paxman. "Did you threaten to overrule him?" he repeated. Twelve times, in total. On each repetition, Michael Howard gave a slightly different response to the question, never quite answering it. And so the pantomime went on, Michael Howard answering the question he wanted to be asked, Jeremy Paxman asking the question he wanted answered. This interview helped to cost Michael Howard the Conservative party leadership.

(The second clip they'll dig out is his attempt to have a serious geopolitical discussion on 3 October 1990, as Berlin partied as Germany reunified. "It's pure Monty Python" said one guest.)

Did Paxman help to take politicians down a peg or two? Of course he did. Did Paxman help to undermine the institutions of Westminster? Very possibly. Did Westminster come up with some method to assert their superiority over mere journalists? Not successfully, and Westminster's failure to rise about sharp challenges is their problem, not the inquisitor's.

Although his formal party political career lasted an hour, Paxman remained a small-p political animal at heart. In 2008, Paxman asked the rapper Dizzee Rascal if he believed in political parties in Britain. Mr. Rascal replied, "Yeah, they exist, I believe in them. But I don't know if I care." The awkward silence lasted forever; Paxman could not empathise with someone who rejected the world where he worked.

After leaving Newsnight in 2014, Paxman had a short series of interviews with famous personalities on Channel 4, and participated in the channel's 2015 Westminster election coverage. Approached to be a candidate for Mayor of London. Paxman declined in short order, saying he would not take the job "for all the eclairs in Paris".

"Geographers now doing well in Saskatchewan"

Bamber Gascoigne had The Christans. Jeremy Paxman has Empire, a landmark authored documentary series. Empire was shown in 2012, and told the story of the British Empire in five hours, never quite declaring whether the host was for or against it. The horrors of the slave trade, the genocide in Tasmania, famines and massacres, all were criticised. But Paxman had kind words for the ordinary administrators, an incorruptable manifestation of distant power; and for the Empire's spasms of moral self-reflection. Perhaps he showed too much of life abroad, and didn't reflect on how the Empire altered things at home. It's a great tale, fascinating television, but it may not be great history.

Empire is one of a dozen books written by Jeremy Paxman. Black Gold, on the coal industry, tells of how great edifices were built from coal, the great suffering when there were explosions and cave-ins down the mines, and the great tumult as coal's decline was mismanaged by successive governments.

Many of Paxman's books have self-explanatory titles. The English and The Political Animal were books on the English and politicians' superegos. Rivers, a book and television series about rivers. His autobiography A Life in Questions is a series of anecdotes about his career, presented in approximately chronological order. Great for lazy biographers wanting to flesh out the first part of his life, less rich in interesting revelations.

On Royalty: A Very Polite Inquiry Into Some Strangely Related Families explored the interrelated royal families in Europe. Why have the Windsor clan endured in England? Sentimentality, habit, a sense that the monarchy is a link to England's past, and somehow a key to its identity.

"Will you please take this seriously!"

Jeremy Paxman's rarely guested on other people's game shows. He was almost thrown off a recording of Crazy Comparisons when he gave the most outlandish answers possible. "What does Tuesday look like?" "A corgi." Paxman turned down Desert Island Discs, Celebrity Big Brother, Strictly Come Dancing, and Celebrity Fifteen-to-One. He eventually did Have I Got News for You in 2018, and Celebrity Bake Off in 2019. Paxman did have interests outside news: he hosted topical discussion programme Start the Week on Radio 4 from 1998 to 2002, and television review show Did You See..? from 1991-93.

He made the news in his own right in the year 2000, when a large cardboard box landed on his desk with a thump. Inside, there was an Enigma machine, as used by the codebreakers at Bletchley Park in the Second World War. The device had been stolen some months earlier, and a ransom demanded for its safe return. Someone was subsequently sent to prison for its theft.

And then there was "pantsgate". In his local gym, Paxman made an off-the-cuff remark that Marks & Spencer underwear did not provide the same level of support as it used to. Stuart Rose, the chairman of M&S, took Paxman for a "quiet" lunch – which just so happened to be in the same restaurant as a journalist, who got wind of the story, and it dominated the headlines for a week.

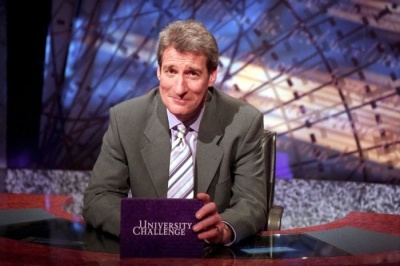

For this column, for the game show world, we know Jeremy Paxman as the host of University Challenge, from its BBC revival in 1994 to the present day. Although he thought Bamber Gascoigne should still host it, a chance meeting with Bambi in the British Library's Reading Room set Thumper straight. "They rang me up about six months ago, but I don't like the sound of it. Too much hard work."

Jeremy Paxman was an excellent choice for University Challenge. He was familiar to the viewers, exuded authority, spoke clearly and briskly, and appeared to have sympathy for the young students. Paxman got the job.

Paxman very nearly lost the job. His first episode recorded (and second transmitted) was between New College Oxford and the University of North London, which had been a university for just two years. The new university against New College, see. It's the sort of little joke to pep up the first round: see also York vs Lancaster, Glasgow vs Edinburgh, and innumerable Oxford College vs Cambridge College battles.

North London get the first bonus, "How many permanent members are there in the United Nations Security Council?" Twenty-five, the incorrect answer. "No, it's five. I expect you were thinking of the total membership of the Council, which is fifteen. Next bonus: what is the total membership of the Security Council."

Oh dear. Obviously, they'll have to stop and edit out that flub, and make sure Paxman never gives information without reading the next questions. New College kicked up a stink, and only the threat to replace them with the reserve team restored order. New College went on to make the series final, losing to Trinity Cambridge featuring Kwasi Kwarteng. Wasn't he famous for something else, briefly?

"Some ignoramus argues the show is biased towards the Oxbridge colleges, or against them, or is anti-Welsh, or something. The only bias is in favour of entertaining television", wrote Paxman in A Life in Questions. Sometimes, it's difficult to see how the producers' changes enhance the entertainment – a move to long and tedious questions in the mid-aughts, a tightening of buzzer discipline about ten years ago, that lugubrious arrangement of "College boy" in the titles. All cause this column to lose interest for a time.

Still, we came back, because students are wonderful and better than a messy format and deserve every chance to show what they can do. And University Challenge can evolve for the better. Twenty years ago, there were so few women on the show; nowadays, we think a team comprised of just blokes is deficient. They wouldn't ask simple questions about how many members the UNSC has, they'd rather quiz on something that needs actual learning, like UN peacekeeping deployments. Questions have got harder, more esoteric, questions have greater relevance to fields of university study.

Sometime after leaving Newsnight, Paxman visibly relaxed on UC. He didn't need to come across as the barking dog, always asking the most aggressive question. He gave more praise than criticism, lightening the mood and making sure everyone had the space to give their best. It's reported that Paxman had a quiet word behind the scenes, to ensure a wider spread of questions, ask about women composers, Black theatre, Indian art, and fewer all-men teams on the show.

Jeremy Paxman has always been quietly on the students' side. One contestant in the mid-90s remembers bringing a t-shirt bearing a picture of the Jules Rimet trophy and the slogan: “Have you noticed how we only win the World Cup under a Labour government?” The anguished producer said: “She can’t wear that on the BBC! It’s a political statement.” Jeremy Paxman, until this point silent in his make-up chair, piped up. “She’s a student. Students are meant to wear things like that. It’s fine”. The great man had spoken, all dissent was quietened and the shirt was permitted on screen.

He's a man who keeps his private life private, and we respect that. The brief biographical details: Jeremy Paxman was in a relationship with Elizabeth Clough for about 35 years; they had three children and split amicably around 2016. He told the world about a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease in 2021; it's been rumoured that this medical condition has contributed to his decision to retire.

For almost three decades of University Challenge, Jeremy Paxman has been as constant as a grandfather clock, ticking along, asking the questions, accepting the answers. He's never sounded convincing when he talks about science, he always sounds much more at home on the arts. Over the years, we've come to accept these foibles. In recent years, his diction has become less clear, his motormouth slowed, replaced by the patina of grace earned from advancing years.

His swansong series has been one of the finest. It began with a tight match between Durham and Bristol, decided on the final starter moments before time. We've seen Cardiff win at a canter and lose by a heartbeat, we've seen a record performance from Southampton. Royal Holloway impressed with their buzzing, UCL had the first mother-and-son combo, Newnham Cambridge were joyful and supportive and brightened up so many Monday nights.

This week, Southampton played Bristol in the second semi-final. Bristol won by 200-70, seizing the game with a run of five starter questions early in the show. Subjects of these starters were varied: Battle of Bosworth, "ARA" words, the Bhagvad Gita (a Hindu scripture), the Berber scholar Ibn Battuta, and Ajaz Patel the cricketer. Jacob McLaughlin's best on the buzzer, eight starters in the semi-final, but he's supported by a very strong and very wide-ranging and very knowledgeable team.

The last act in Jeremy Paxman's career – and we must brace ourselves that it'll be his final substantial television engagement – will be tomorrow's University Challenge final. Like the series opener, it'll be between Durham and Bristol. We hope it's full of two teams of student stars giving their best. We hope it's a suitable send-off for someone who has left his mark on television and on wider society.

In other news

Congrats to Patrick Kielty, who has been appointed host of The Late Late Show. Patrick's come a long way since the days of Last Chance Lottery and will take over the biggest show on Irish telly in the autumn. The current host, Ryan Tubridy, stepped down this week after fourteen years in charge.

Congrats also to Käärijä, winner of the "You're a Vision" award for the most striking and memorable outfit at the recent Eurovision Song Contest. We hear that his song, "Cha cha cha", has been adopted by North American sportsball teams hoping to stoke up the atmosphere, replacing the one that goes "Come on come on!"

The death of Rolf Harris has been announced, aged 93. His game show credits included A Song for Europe, commentary on the Eurovision Song Contest, and art programme Star Portraits. Known in the last century as an artist, singer, and animal-lover, Harris will only be remembered because he was convicted for indecent assault about ten years ago.

Russell Davies of The Russell Davies Song Show added his memories. "1988: chaired a Punch Lunch where Rolf Harris was the main guest. All he wanted to do was point around the table and whisper: "Who's she? And who's she? What does *she* do?" When I mentioned his character Willoughby on children's TV, he claimed not to remember drawing him. #creep".

Michael Fenton Stevens added, "I once asked him to sign something for my kids class and he said 'if I had a pound for every f***king *unt who's asked that!' And walked away. We were filming together at the time. I didn't speak to him again apart from on camera with my lines."

This column remembers Harris as the star attraction at our university Freshers' ball. The Anorak Zone remembered watching Harris on telly with Granny Zone, and summed it up. "When these people do what they do, they don't just destroy lives, they retroactively destroy memories."

Research question from Bother's Bar Discord: "Did Countdown ever win its slot" (have more viewers than any other programme on at the time)? Almost certainly, though we can't give you chapter and verse of when this happened. Countdown went out at 4.30pm until 2001, scored around 3.5 million viewers in deep winter; even in the peak of summer it would get 2.5 million viewers. The most popular children's programmes were kept until the autumn, as both CBBC and CITV knew their audience had better things to do than watch tv. While new episodes of Byker Grove and Knightmare would get 3.5 million and more, repeats struggled to get half of that, and most of the other shows will have been less popular than Countdown. Sadly, even this column doesn't have show-by-show data from 1989, so we cannot say it happened on such-and-such a date.

We can say that Ronan Higginson has achieved the pinnacle of Countdown mastery: a Perfect Game. No longer word in any of the rounds, every numbers game solved, the conundrum found. In the forty years of Countdown, less than a dozen players have achieved perfection.

Our friends at TV Show & Telly talk with Luke Shiach, producer of shows like Have I Got News for You, Celebability, House of Games (1), and Pick Me!. But what is his exciting tale about stationery? Listen to find out.

Channel 4's commissioned a third series of Richard Bacon's I Literally Just Told You hosted by Jimmy Carr. It's the show where they write the questions as they go along, and almost anything can happen.

Channel 4's also announced Five Star Kitchen, where Michel Roux Jr tries to find a great new chef – someone who will impress for years and years, and not be the hottest thing for a few weeks before they take a wrong turn on the difficult third album. That series starts on 8 June.

Next Saturday and Sunday sees the 24 Hour Game Show Marathon, a charity stream put together with love and care by some of Philadelphia's loveliest game show fans. They'll be playing Moneybags at 11pm our time, The Wheel at 1am, Countdown at 7am, and will the contestants have any Concentration left in hour 23?

It's the Got Talent Live Shows (VM1 and ITV, Mon-Fri), leading up to next Sunday's final. Sitting on a Fortune with that nice Gary Lineker is back (ITV, Sun). Radio 4's got a new series of everyone's fave fib-based panel show, and that's The Unbelievable Truth (Mon). New episodes of Pointless, too (BBC1, from Mon). Finals night for Masterchef (BBC1, Tue-Thu), Taskmaster (C4, Thu), and Ireland's Smartest (RTÉ1, next Sun) – we plan to explain this quiz when we're back in two weeks' time.

Pictures: BBC, Weaver, Central, Granada, EBU/Corinne Cumming, Yorkshire. The word "socialism" was the conundrum scramble. Special thanks to the staff at Hillscourt Conference Centre.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.