Weaver's Week 2021-01-24

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

This week, we begin a two-part series on a cultural touchstone, one of the most famous game shows on television. We speak, of course, about

Contents |

Lingo

Ralph Andrews Productions, 1987-8

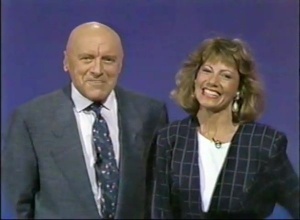

Let us start the tale at its very beginning. Lingo was originally created by Ralph Andrews, and syndicated for six months in the winter of 1987-8. Ralph presented the show, with hostess Margaux MacKenzie, and called it "television's most challenging game". It's a game of five-letter words and fast thinking.

The show is a mixture of words and drawing balls, a combination of linguistics and bingo. Our players start with a five-by-five bingo grid, with seven spaces marked off. So far, so bingo.

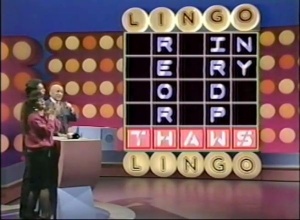

Then comes the word element of the game. Here's a five-letter word, with its first letter indicated. What's the word? Say it, and spell it.

It's unlikely you'll guess a word beginning with "P" on the first go. So they give hints. If a letter's in the right place, it'll drop down to the next line. If it's in the word but somewhere else, it'll be indicated. And if there's no mark on a letter, it's not in the word at all. Five guesses to find the word: it's got to be a valid word, spelled correctly, and started within five seconds.

Get the word right, and our players can each draw a ball out of the bingo bag beneath their desk. Mark the number off their card, and hope to make a line of marked-off spaces. That's a "Lingo", and earns the team a shot at the bonus round; for some of the series, it also carried a prize of its own.

Two jackpot balls are in the bag. Should the team pull both of these out, and go on to win the game, they'll win the show's rolling jackpot. It starts at $1000 and increases by $500 per show.

But the bag also contains some red balls. Draw any of these and the team instantly loses control, and the other team takes on the next word. Play also passes if the team fails to guess the word in five turns, or fails to give (or spell) a real word.

Lingo is played by two teams of two. The players know each other before starting the game, and – as is traditional on North American games – clap and applaud themselves throughout the game. There's some Early Installment Weirdness here, as the hostess Margaux steps forward for every drawing of the balls.

It quickly becomes clear that there is strategy to the show: know a lot of five letter words without repeated letters, and with distinct sets of letters. If you can knock off most of the possibilities, the game becomes much more simple.

Play passes back and forth until one of the teams gets a line, and forms a "Lingo". They qualify for the bonus round.

Lingo in reverse

The bonus round involves a lot of balls. 38, to be precise. They're all under the champions' desk, and the object of the game is to not make a Lingo. To start the game, our players are spotted some money – $500 if they made a horizontal or vertical line, $1000 for a diagonal, and $2000 for two lines – a rare Double Lingo.

On each turn, the champions are to find another five-letter word. They're given the initial letter, and one other. For every guess to find the word, the champs draw out a ball – so if you find "Merit" in three guesses, you draw three balls out. Miss the word completely and you're pulling seven balls.

On the screen is a bingo board, with 16 spaces filled – in a star pattern. If our players pull out the middle square, or any two to complete a line, it's game over. But when they complete their turn successfully – or pull out the one Golden Ball – the players double their winnings.

The champions can stop after completing a turn, and bank the money they've got. Should they play on and survive five turns, they'll win the jackpot – anything up to $64,000. That's big money, about two year's annual income for the average household.

Like Going for Gold, it was difficult to leave Lingo – you'd only reach the exit if you lost two games, or won four. Unlike Going for Gold, there were some funding problems with the show. Many winners were never paid their announced winnings, and the prizes were awarded in Canadian dollars – worth about 70 cent south of the border. With few stations taking the show, Lingo went off air at Easter 1988.

Lingo-on-Thames

As with almost all North American shows, there's been a version over here. Martin Daniels hosted on Thursday evenings in spring 1988.

Almost the same rules as on the GSN version, find words, draw balls. The biggest difference is that the teams are playing for cash throughout – £50 per word, £100 per line. When a team makes a line on their card, they keep playing on that card until the end of the game.

The jackpot balls were retained from the original, but now became "prize balls", for durables such as a CD player or a microwave oven. It's an ITV network show in primetime, they almost have to give away such prizes. And this is a timed event, we viewers see a countdown clock on screen for the final minute of play.

Martin Daniels is a capable host, though he doesn't bring out much of the contestants' personalities. Nor does he yet have the years of experience his father Paul brought. And the graphics on Lingo looked dated: blocky letters and simple beeps were a mile behind First Class or the clear captions of Every Second Counts.

The final round, the bonus round, is the No Lingo idea they had in Canada. Martin builds up the tension, and perhaps this final round is a little bit slower than it could be. The team is given £100 to start with, and can double it up to the jackpot of £3200 – plus whatever they won in the main game, so the thick end of £4000 is possible. A decent prize, near the IBA's cap, about three months' wages for the average family.

But while Lingo was decent, and had a catchy tune sung by Panacea, it was the latest in a long line of word games. Countdown was running, Catchword had done good business on BBC2, and Andrew O'Connor's Chain Letters was the shiny thing on daytime television. It wasn't a huge surprise when Chain Letters took over this mid-evening slot in the autumn.

Wie is de Lingo?

It seems that every culture has a very long-running programme imported from overseas. On these islands, we have University Challenge (a version of College Bowl) and Countdown (a take on Des Chiffres et des Lettres). France took Questions Pour un Champion to its heart, based on one-series flop Run for the Money via the more successful Going for Gold. The Dutch? They've got Lingo.

Producers Jan Meulendijks and Harry de Winter bought up the rights to Lingo and made episodes for the VARA organisation. It proved to be a huge hit, an energetic 20-minute brain workout that just hit the right spot. Lingo proved so successful that de Winter bought the worldwide rights to the format, licensed it across Europe, and used the money to start his own production company IDTV. You'll know them from shows like Wie is de Mol?.

The first host was Robert ten Brink, a man with very large hair. He was known as the host of Jeugdjournaal, the local equivalent of John Craven's Newsround or RTÉ News2day. He'd also hosted Cijfers en Letters, the local version of Countdown. But he wasn't the star of the show. That honour went to a revolving stage.

Contestants revolved on, Robert talked to them, and played the game. Five letter words, guesses are scored and bingo numbers are drawn. There is a jackpot, starts at zero and increases with every correct word by 50 guilder (€22,70; then about £17). Win that jackpot by drawing out the three green balls in the main game, and look for it to rise into the thousands of guilder.

The losing team keeps their main game winnings – 50 guilder per word, 100 guilder for a line. When one team gets a line, both get new bingo cards. Whichever team has the most money in the main game goes on to play the No Lingo endgame, using their main game winnings as the starting stake. A typical winning score of 300 guilder can double and double and keep going up to 9600.

The computer noises are basic beeps, and the graphics are primitive – but they're clear, still an advance on Thames' version from eighteen months earlier. Robert brings out tension in the final round, snatching balls out of the contestants' hands as soon as they're drawn. But the best part of the show is the rotating stage, turning from the two desks of the main game to the one desk of the bonus round.

After a few years, Ten Brink left VARA and left Lingo. The new host was François Boulangé, a man who didn't want to make himself the star of the show. He comes across as something of a mad professor, the kindly sort who will reward you for amusing and entertaining him.

The set looks different, metal sculptures and wooden blocks give it a solid feel. No revolving stage, though. The graphics have improved, the typeface is cleaner and the scores are displayed in an unfussy typeface. The game remains the same, the scoring remains the same: 50 guilder per word to the players and into the jackpot, 100 guilder for a line, and still the No Lingo final. One tiny change: when a team gets a line, only that team gets a new card.

Boulangé stepped down in 2000, replaced by Nance Coolen. We've not been able to find any editions she hosted. During her time on the show, the final changed into a more positive achievement: solve words to draw balls, and make lines to win big money.

The next show we've found is from 2012, and it's somewhat closer to the game we see today. For that reason, we'll stop here, and complete the story next week.

In other news

Democracy season continues, with the results from the UKGameshows/Bothers' Bar Poll of the Year. Only Connect retained its place atop the Golden Five. Beat the Chasers was the Best New Show, and Ash the Bash's streaming goodness was the best show not on your telly. The Chop was judged Worst New Show, more for the poor contestant selection than anything wrong with the show.

Democracy season continues, with The Beano Power Awards. The comic for primary school children runs a poll through its website, and includes a Best Show of the Year category. This year's nominations: Got Talent, I'm a Celebrity, Strictly Come Dancing, Bake Off, The Masked Singer. What does your target audience of 6-year-olds love? We'll find out in a week or two.

That's how to build a wheel Slap bass, a funky drum track, a huge brass section, and an unexpected clavinet. Paul Farrer takes nine minutes to explain the soundtrack to The Wheel.

Jason Manford is Unbeatable, according to his new show. The Crackerjack! star and First & Last host will host a new afternoon show later in the year, where contestants look for the unbeatable answer. It's a Possessed format, produced by Zoë Tait and Glenn Hugill.

It sounds a little bit frightning: Zoe Lyons has got daytime quiz Lightning (BBC2, from Mon). Finals week on Junior Bake Off (C4, weekdays), and Celebrity Best Home Cook arrives on BBC1 (Tue, Wed). Next Saturday's Catchpoint teams Kate Bottley with Richard Coles, both celebrity vicars in the same room.

But the big thing next weekend is Royal Flush's Big Charity Stream. Scheduled for most of next Saturday afternoon, and raising money for The Samaritans, we're promised many great stars of the internet. Paul Farrer And His Lovely Lovely Soundtrack! Daniel Peake and Ball 35! Tom Scott and His Amazing Red Shirt! All this, and much much more.

Photo credits: Ralph Andrews Productions, Game Show Network, Thames, VARA/IDTV, BBC Childrens' Productions.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.