Weaver's Week 2025-05-04

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

"We want to see blood being spilled on the board! Cut and thrust! We want to see chess like gladiators across the board!" – Cathy Forbes, speaking on the Channel 4 world championship coverage, 1993.

Contents |

Chess Masters Colon The Endgame

Curve Media for BBC2, 10 March – 28 April

At least, we think the English chess champion referred to "gladiators" as in the Roman era entertainers, not "Gladiators" as in the popular ITV physical challenge. But it's an interesting idea: could television treat chess – the most cerebral of pastimes – with the same combination of fun and awe we get from Gladiators?

Back in the 1980s, Bill Hartston had taught children (including this column) how to play chess, on the unimaginatively-titled Play Chess. There had been a weekly tournament, The Master Game, featuring up-and-coming players like Nigel Short and some international stars. The triennial World Championships had weekly highlights programmes, moves analysed and picked over by other experts. A championship match in 1984-5 between Anatoly Karpov and Gary Kasparov dragged on, and on, and on; it became front-page news thanks to Raymond Keene's witty and accurate reporting.

Keene was also the leading force to bring the Karpov-Kasparov rematch to London in 1986, and helped to ensure that Kasparov's championship match against Short would be the media frenzy of autumn 1993. Channel 4 had live coverage, and exclusive access to the players. BBC2 had spoiler coverage, which concentrated a lot more on the actual chess being played. Although the Beeb continued to give chess a spot on its schedules for a few championship cycles, it's not been a regular feature on television since about the turn of the century. The nascent BBC4 could have made a regular series about "mind games", which would doubtless have included a regular chess spot, but chose not to.

You'll have spotted that the BBC treated chess at one of two levels: either an elite sport (covering the world championships, or a very high-level tournament), or as something for beginners. Unlike the Beeb's coverage of the card game bridge – and commercial channel's coverage of poker some years later – there was no attempt to show more ordinary players, and help the viewer to improve their own chess.

Channel 4's world championship coverage had a lot of time to fill: when the grandmasters are given two hours to make 40 moves, they'll use every second of it, and that leads to an awful lot of dead air and flannel and filling. Channel 4 made a half-hearted attempt to humanise Short and Kasparov, to get us rooting for one or the other based on their personalities. It didn't work, most people who watched live chess were there because they wanted to see the moves, not to learn just how physically fit top players needed to be.

What happened on Chess Masters?

As we say, chess had been absent from television screens for about a quarter of a century. Until this year, until Chess Masters came bounding onto screens. Twelve players take part, split into two groups of six. Each group followed a parallel path.

Show 1: head-to-head chess matches between the players, randomly assigned. Winners are safe for next week. Losers are shown a chess puzzle, whoever solves the puzzle perfectly the fastest (or otherwise does the best) is safe for next week. The two losers play an elimination match, from which the loser is eliminated.

Show 2: a chestnut of a puzzle for the five remaining contestants, best performance is safe for next week. The remaining players are drawn and play a king-and-three-pawns game, which used to be a standard test of white's attack versus black's defence but seemed to take these players by surprise. Losers of this challenge play an elimination match, loser's eliminated.

Show 3: another puzzle for the four contestants, this time to remember and reproduce a particular position. Best performer picks their pair for a two-versus-two match, and the winning side is through to the semis. Losing side face off against each other in another elimination match, this time with the pieces arranged according to Fischer Random Chess. Loser is, again, eliminated.

Repeat for the other group.

Semi-final: six players remain, again assigned into pairs. Each player picks their back rank of pieces, up to a maximum value of 22 pawns (so you can have two queens and a knight, or queen rook knight and two bishops, or....) Winners are safe for next week. Losers play a simultaneous chess game against child prodigy Bodhana Sivanandan, who was only nine years old when they recorded this show. Whoever loses to Bodhana fastest is eliminated. The remaining two play a speed elimination match; loser is out.

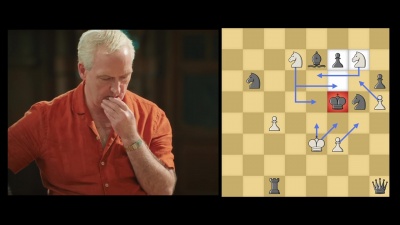

Thalia ponders a problem: white mates in two against any defence. We'll give you the answer later. (Curve)

Thalia ponders a problem: white mates in two against any defence. We'll give you the answer later. (Curve)

Final: a series of puzzles, with the worst performer eliminated. Then it's a simultaneous match against David Howell, the show's resident grandmaster; again, whoever loses first is out. The final pair play a standard match, and the winner is the winner.

How good was Chess Masters?

This column loves nothing more than to praise a good show. We like to say what they did right, and how other programmes can emulate something. Chess Masters left us rather lacking in reasons to cheer.

For the first time in forever, television chess has included players at the club level. They're good, but they're not working on a higher plane. None of our twelve are international championship ultra-masters. None of them have brows as high as Ant McPartlin's, or intellects as fearsome as an Only Connecter. These are relatively ordinary people, they happen to be skilled and practised in the disciplines. They will make plausible blunders; they may be inspiration for people who know chess to find a club, maybe move from "dabbler" to "decent".

The challenges were varied, they had some texture to them. A lot of standard chess, certainly, but also some unusual variants to allow variety, and puzzles to solve. The winners had to prove their chess ability, and their ability to improvise around unexpected restrictions.

David Howell was the show's resident grandmaster. He knew what he was talking about, and has the gift to be able to communicate clearly and precisely to the viewer. He had a big graphics board, so could demonstrate tactical points (the pin, the fork, the triple stack) and show us possibilities of how the game might play out. His commentary assumed little knowledge of how strategy works on the chess board.

The Coal Exchange in Cardiff was the filming location: grandiose, imposing, and looked beautiful. Erran Baron Cohen wrote music for the show, it was non-intrusive and subtly highlighted the emotional points.

The winner earned their prize. There was never a sense that they'd lucked into the last stage; indeed, the best players in each group rose to the top and we could not quibble with the final six.

But that is as much as we can completely praise.

What did Chess Masters do wrong?

We'll start with the pacing, which was all sorts of bizarre. The series opened with three boards in play at once, three games completed and edited down to about twelve minutes of airtime. We were asked to try and follow three matches at the same time, keep three different boards and six different styles in our heads. And, intercut with these clips, profiles of the players we're meeting tonight. Chess Masters gave the viewer masses of work: it asked us to do about twelve different things at once. It's no wonder that we got lost: didn't properly think about some of the winners, couldn't appreciate the chess being played.

Compare against Only Connect, which occupied this 8pm Monday spot earlier in the year: however fiendish and difficult the questions are, we're only ever being asked to assimilate one piece of information, only need to think about one topic at a time. Or compare against Soccer Saturday: flitting from game to game works for other sports, where scoring is rare and long periods are quite dull, but it doesn't work for chess, where every move matters. Or compare against Genius Game, which asks us to follow the thread of a highly complex task, but never overloads us with too much information.

The show's speed also meant we couldn't get deeply into the games. We saw blunders, we saw moves being missed, but we didn't see the patient build-up to construct the traps into which opponents fell. For the eliminator games, this was slightly mitigated by putting the whole games (including commentary) online.

Host for the programme was Sue Perkins, the personable and entirely lovely presenter. Third wheel was Anthony Mathurin, a contestant from The Traitors a few years ago; he was with David in the analysis room, and seemed to be employed as someone to ask the right questions for David to explain something. Could Anthony have hosted the show himself? Maybe, but Sue is a familiar face and known to be brilliant at putting people at their ease.

But the main problem was that Chess Masters didn't know where it was aiming. There was no attempt to explain the basics of chess – how the pieces move, what the basic idea is, so this show wasn't going to work for viewers who knew nothing of chess. Nor was there any effort to get into the players' heads, they weren't asked to narrate their thoughts as happened on The Master Game. Almost every game ended in checkmate, there were no draws; one might conclude that the standard of play was noticeably lower than the grandmaster game.

Not a show for beginners, not a show for greatness. Is it a show where the players' personalities were allowed to shine? They tried to bring out each player with a nickname – "the unruly knight", "the tactician", "the princess", "the aggressor" – but it quickly became clear that these were tiny differences in style magnified for the convenience of producers. Perhaps they were intended as a liferaft to flailing viewers, but surely any viewer will have turned off in the confusing opening minutes and thought "naah, watch The Eastenders instead".

Before the series began, producer Camilla Lewis gave interviews to the daily tabloids about how she was inspired to make the show after seeing the profound effect the game had on her teenage child during difficult times. She wanted to show the "theraputic and transformative power of chess"; quite honestly, we do not recall this aspect reflected on screen at all. We were also warned of "trash talk" and "it gets quite spicy"; no disrespect was heard, and there would be more spice in an exceptionally bland curry.

Whether by accident or design, the format allowed the best players to skip half of the heats. Win your first match, you're up to the "winners' balcony" and into the next show. Win the puzzle and you're back on the balcony. Win the pairs match and you're into the semi-finals, having had about a quarter-hour of screen time. Someone who is at risk of elimination can get over an hour on screen, and this feels bizarre. If they wanted to show the winner's "chess journey", perhaps do a Strictly Come Chessing: take a group of eight, give them intense coaching, play variations each week, and see who's the best at the end of the series.

There were other bizarre scheduling decisions. In the semi-finals, losers of the first round matches played a simultaneous game against young guest Bodhana Sivanandan. In the finals, the last three played a simultaneous game against international grand master David Howell. Which was the greater honour; the bloke who's been hanging around the studio all tournament, or the bright young thing who has come in as a guest? One could argue that the two simultaneous games should have been the other way round.

And the presentation was poor. Chess boards were often shown from the side, they concentrated more on the shadows cast by the pieces and less on allowing us to see the position. We were able to see full-board diagrams through the various world championships, and it's bizarre that they couldn't show something similar in the modern era. Had this programme gone out in 1994, following the Short-Kasparov hype, we would have thought it an admirable if slightly flawed effort; in the warm light of 2025, it feels dated.

Viewing figures were rotten: we weren't expecting the two million of Only Connect, but we were expecting the show to rate around one million, and it didn't get close to that. Worse, the failure of Chess Masters has derailed the show after it, Quizzy Mondays lynchpin University Challenge has dropped almost half-a-million viewers and is level with Mastermind for the first week in forever.

This column loves to see people who show their passions, let us share in the joy, allow us to root for them. The contestants shared their passion, showed off what they love, clearly had a great time doing so. This column hasn't played chess since the last century, never played it very well, but knows enough to know that these contestants have put in plenty of effort and been properly rewarded. Well done to them all.

It's a desperate shame that the surrounding programme was so underwhelming, and didn't seem to know if it was chess as a sport, or a human drama told through chess. Perhaps the producers might look at The Piano, which also takes talented amateurs and gives them a bigger stage; why does that work in a way Chess Masters did not? We critique the show in the hope of building a better one; if there is to be a second series, radical surgery is required.

In other news

Sorry to hear that Philip Lowrie has died. Best known as Dennis Tanner in ITV drama Coronation Street, he'll be remembered on this site as one of The Voices of Fifteen-to-One.

This used to be our playground Sky's sports comedy panel show A League of Their Own is coming to an end this autumn, after 15 years and 20 series on air. Phil Edgar-Jones, head of unscripted stuff, said, "We're incredibly proud of the show – it's been a cornerstone of Sky's entertainment line-up for fifteen years and has delivered endless laughter, heart, and unforgettable moments. Huge thanks to the brilliant team at CPL Productions and to our fantastic on-screen line-up – Romesh, Jamie, Jill and Micah – who continue to bring such energy and chemistry to the show." This column is glad that ALOTO will get the chance to say goodbye properly, and to be cheered by its many fans.

Scribbled out No such farewell tour for Pictionary, which hasn't been renewed by ITV. The show, where Mel Giedroyc invites teams to draw something, ran to minimal audiences in January.

Good news! We hear that Puzzling, the Channel 5 quiz where they had some fun rounds and some plodding ones, is to come back.

Bad news! The Puzzling revival will be all-celebrities, no lovely members of the public.

Good news! Team captains will be the delightful Sally Lindsay and the professionally-smart Carol Vorderman.

Bad news! The host will be Jeremy Vine. Could they not afford someone with more professionalism and gravitas, like Kate Thornton?

Dani Harvie and Chris Rhodes have been in touch, about their Top Quiz! podcast. The blurb is:

- Two titans of vintage British quiz show history are resurrected and go head-to-head in a knockout tournament to decide which is the UK's 'Top Quiz!' We relive the golden age of gameshow entertainment with brand new questions in the style of each episode's chosen shows – and with plenty of laughs along the way.

First episode pits Blankety Blank against 3-2-1. Don't expect a discussion of each show's plus and minus points, like the Retroquizzical podcast from a few years ago. Here, we get questions about celebrities of the era, in the style of Blankety Blank prompts and 3-2-1 clues. Top Quiz! is on Apple podcasts, Spotify, and RSS.

Quizzy Mondays

Spectacular success for Ronnie O'Sullivan and Luca Brecel in this week's Mastermind, which rather looked like the Big Break revival we didn't know we didn't need.

What happens when the irresistible force meets the irresistible force? We found out on University Challenge as Harrison Whittaker, the one-man buzzer of Darwin Cambridge, met Thomas Hart and Oscar Siddle of Warwick. The first two starters – famous Rachels, and the geography of Honduras – fell to young Whittaker, and we began to pencil in another Cambridge derby.

Not so fast! Warwick reeled off five starters in a row – including contributions from science specialist Ananya Govindarajan and philosopher Benjamin Watson – to pull out a sixty-point lead. Two starters later, that's a ten-point lead, and we're into a period where the lead swings this way, then that way, and quite often ends up as a tie.

Rose poetry gives Trinity a set of bonuses on artworks inspired by Cupid and Psyche, but just one bonus. Warwick respond with pain sensors and scientific concepts represented by Q, to take a thin lead. A dropped starter, then another one – this is all time off the clock, one team may curse this shortly. Harrison Whittaker buzzes on a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and two on films. Thomas Hart for Warwick spits out "grass" as a type of plant, and adds two on electric circuits.

It'll all come down to the final starter, on prime ministers who were succeeded by someone called Robert. That's another hit for Thomas Hart, and Warwick end up winners, 180-160. This match was won on the buzzers, Warwick took 10 starters to Darwin's 8, and it's credit to the Cambridge side that they were so close to the win. Warwick will play the final against Christ's Cambridge.

Genius Game

Genius Game is not a quiz, and it doesn't go out on Mondays. It is well worth your time. We intend to recap weekly up to episode six, and then cover the final episodes when we review the show fully after Eurovision.

David Tennant is the host, the attraction to hook people in. You know, from Doctor Who and Broadchurch, shows you like even if you don't always understand every detail. Remember how good it is to watch someone quick-witted understand every detail and explain it back to you? David's done that through his career.

David is not the star of the show: he's only watching the game, controlling it. Eleven people, selected for emotional and intellectual intelligence, are the real stars.

In the opening episode, we briefly meet the contestants as they meet each other, then it's straight into the main game. A bank robbery; players raid for their own accounts, but can work and scheme together.

The die is cast in the opening moments: a group of six gravitates towards one room, a group of five moves towards another room, and the smaller group is squeezed out. Both groups come up with the winning tactical play, but only the larger group has the numbers and trust to pull it off. Their target had chances to stir the pot, but sat back and accepted his fate.

Across both episodes this week, the winning social play is not to piss people off. One player made a casual comment that rubbed someone up the wrong way, and paid for it. Another player openly lied to a group, and while there weren't any consequences this week, it's the sort of thing that will surely come back at the junction of molars and backside.

The winning strategic play is to fly a bit under the radar, don't draw attention to yourself, because the loser gets to pick their opponent in the "death match" (it's an elimination, nobody dies, this might be post-watershed but it still ain't The Hunger Games). But if you fly too far under the radar, nobody has a chance to form a solid bond with you, and you might be the least bad option. And is it better in the long run to take a knock in early rounds, so you aren't cruising into the last week like certain contestants on The Traitors?

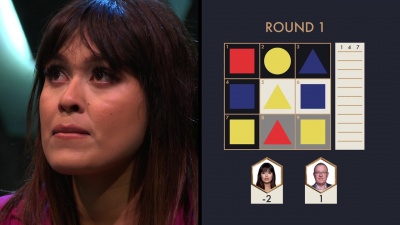

Bhasha tries to identify groups that have the same shape, colour, background; or different shape, color, background; or some combo thereof. (Remarkable Entertainment)

Bhasha tries to identify groups that have the same shape, colour, background; or different shape, color, background; or some combo thereof. (Remarkable Entertainment)

"Death match" puts the genius into Genius Game, finding the sets under certain conditions, remembering the colours and positions of things on a grid. We had to watch the explanation twice to understand it, and will need to go through the games again with liberal use of freeze-frame and screengrab.

Even in these opening hours, contestants were setting up alliances for the end, and setting up rivalries to follow. And there's the added meta-game of the Garnets, which were only used as half-hearted attempts to bribe other players.

Genius Game is not the Darwinian survival of 99 to Beat. It's not the wise-cracking whittle of The 1% Club. Genius Game is Survivor in clothes as smart as the players.

Continues on ITV next Wednesday and Thursday. And if you want to know more about the episodes you've seen, the show's Assistant Producer Alex McMillan talks to contestants and crew in the Dealer's Room podcast, which you can find on Spotify, Apple, and RSS.

For Dermot O'Leary, Silence is Golden; can the audience keep any of their massive prize? (Dave, Mon). Grand final for Dubhlain DIY (BBC Alba, Mon) and 99 to Beat (ITV, Sat). Next Saturday continues to have Gladiators everywhere, they're on Bridge of Lies; Jedward make their Blankety Blank debut.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.