Weaver's Week 2009-06-28

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Readers with absurdly retentive memories, or who are Claudia Winkleman, might recollect last year's Eurovision Dance Contest. It was won by TVP's entrants Marcin Mroczek and Edyta Herbus, who performed something we dubbed "Fantasia on Michael Jackson When He Was Famous". The subject of this interpretative performance died on Thursday, having survived the competition by barely a month.

Steve Race

| We must also note the death of Steve Race, the chairman on over 500 episodes of My Music. Born in Lincoln on April Fool's Day 1921, Race entered the Royal Academy of Music in 1939, and his wartime service was providing entertainment for the RAF band. After the war, he worked with leading jazz bands of the day. He became a popular entertainer via the children's programme Whirligig: one of the puppets would ask Steve to "play tunes on the old Joanna". He was appointed the light music adviser to the independent broadcaster Associated-Rediffusion, and regularly conducted the house orchestra.

Race hosted the radio programme Jazz In Perspective, which quickly gathered a reputation thanks to the host's forthright opinions. He regularly guested on the lightly topical discussion show Any Questions?, presented Home in the Afternoon and its successor PM Reports, and was the musical mistakes man for Many a Slip, the spot-the-error game show hosted by Roy Plomley. It's as the host of My Music that Steve Race will be best remembered. From 1967 to 1994, he was the driving force behind the panel game; not only did he presented it, but he also researched the show, and selected the guests. In writing the questions, Race took to sleeping and driving with a notepad within easy reach, so he could scribble down questions that might give informative or funny answers. Steve Race was also a writer, with a column for The Listener, seven books, and a regular engagement compiling a crossword for the Daily Telegraph. He was made a Freeman of the City of London in 1982, and appointed OBE in 1992. He died last Tuesday. |

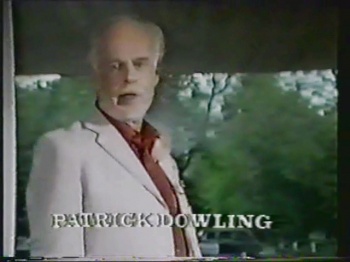

Patrick Dowling

| Patrick Dowling was born on 19 August 1919. His early life, and what we presume was his service in the war, have mostly evaded our limited research abilities. We do know that he worked in repertory theatre after the war, often travelling home on the milk trains that rain during the night.

Dowling had joined the BBC in 1955, and worked on the 1957 television version of The Railway Children. By 1959 he was directing programmes for the Children's Department. The Cabin in the Clearing was the story of a resourceful family under threat in the Ohio wilderness. McGown and Doherty's "The Hill and Beyond" records how the programme had been made just five years before, and the script had been recycled for this new version. It featured Patrick Troughton in a supporting role. The BFI catalogue shows that a few other of Dowling's early works have survived – he presented Adventure Playground (1963), in which some waste ground in Grimsby was converted into an adventure playground. He directed Fascinating Facts (1963), hosted by Donal Donnelly; and Working With a Computer (1965), in which various everyday tasks are put onto computers. | |

| Throughout this time, the BBC had been transmitting a monthly programme for deaf children. With the bluntness in titles that was still the fashion, For Deaf Children was a magazine programme, with close-ups of the presenters' faces allowing children to lip-read, with captions in bold type. Even upon its launch in the late 1950s, the programme had been seen as mildly patronising, and the BBC were glad to take an excuse to make a less didactic show.

The replacement was Vision On (1964-76), a programme that operated exclusively in the world of the visual, and that would be produced throughout by Patrick Dowling. Pat Keysall and Tony Hart were the most familiar faces on the show, subsequently joined by madcap inventor Wilf Lunn, and mime acts Ben Benison and Sylveste McCoy (as he then was). Vision On was a programme that quite deliberately set out to entertain all children; the lack of speech meant that deaf and hearing-impaired youngsters weren't excluded, but nor were they singled out for special treatment. Vision On really hit its stride in 1969, under the direction of Alan Russell, the future Record Breakers director. A typical episode would see Pat and Ben transform themselves into a fantasy land, perhaps being chased out by a tiger that Tony's hands drew through stop-motion photography. Then we'd have The Gallery, in which viewers' paintings and drawings were shown. "We can't return your paintings, but there's a prize for those we do show," was the traditional conclusion. Susanne would ride on her tortoise, Humphrey, and amongst the many animations dotted throughout the show, there would be something from Cosgrave Hall, something from Peter Sproxton and David Lord. | |

| In 1971, Clive Doig joined the Vision On team, to direct one programme. He'd already spent something over a decade as a cameraman and floor manager. Dowling spotted Doig's genius, and the pair worked together as a team for the next six years. Each week's show had a central theme, and it was a year's work to piece together the sixteen shows for transmission in the spring. The programme was ambitious, perhaps too ambitious: one plan that never quite came off was to convert a gasometer into a giant birthday cake, complete with an oversized candle on top.

Vision On was phenomenally successful, and recognised by the industry. It won the Harlequin Award for children's programmes in 1970, the international Prix Jeunesse in 1972, and the overall BAFTA for Best Specialised Series in 1973, beating out such makeweights as Bronowski's The Ascent of Man. The series came to an end in 1976, when Dowling sensed he was beginning to run out of ideas. It could almost be said that Vision On split into two. Though Pat Keynsall left regular television work, Tony Hart had been very famous before, and would go on to host Take Hart, produced by Dowling. The show would go on to win the Harlequin Factual award in 1977. Lord and Sproxton continued to make animations for Take Hart, and the spin-off series The Amazing Adventures of Morph won the Harlequin for Drama and Light Entertainment in 1980, and a BAFTA in 1984. The non-art energy – Wilf Lunn, the mimes – went under the aegis of Doig, and eventually emerged as Jigsaw. A knowing jigsaw piece guided an Alice-in-Wonderland (Janet Ellis) through surreal sketches and comedy routines, in the framework of hinting at letters to form a word. | |

| But we digress. Patrick Dowling had already begun another simple but revolutionary show, Why Don't You..? The conceit was that children would write in with their jokes and makes and bakes, and stage-school kids would demonstrate them. The objective was to persuade youngsters to switch off their television sets and go out and do something less boring instead. Initially based in Bristol, from where it won a Harlequin for Factual Programmes in 1975, the show passed around the BBC nations, visiting Belfast and Newcastle before finally resting in Liverpool, where it met young scriptwriter Russell T. Davies.

But we digress again. In 1974, Will Crowther had written a computer program. Crowther was an experienced caver, and took the map of some caves he was exploring, and converted it into a guided tour for less experienced speleologists. Don Woods had taken the map and underlying idea, added in a fantasy quest in the style of Dungeons and Dragons (invented 1973), and distributed it on the ARPANET. The program, by now called "Advent", came to the attention of Patrick Dowling, who initially contacted Douglas Adams to see if he could turn that idea into a television format. Adams was unable to help – neither man was quite sure what Dowling's idea would become when translated to television, and anyway Adams had contracted to write a second radio series of The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which he would work on continuously before, during, and even after its January 1980 transmission. Instead, Dowling worked with Ian Oliver on what would become The Adventure Game. Games shop owner Eamonn Bloomfield talked them through the concept of Dungeons and Dragons, and Monica Sims, by now the Head of Children's Programmes, gave Patrick the keys to the cupboard and trusted him to deliver quality programmes. | |

| This column has discussed the mechanics of The Adventure Game previously: see the weeks of 19 and 26 August 2007, and of 29 June and 6 July 2008. It suffices to say that it built on the mechanics of logic puzzles and added a twist – using a pair of pliers to crack nuts is obvious, using them as the centre of an electromagnet is only trivial in retrospect. There were many special effects, including an entirely dark set filmed using cameras left over from Foxwatch.

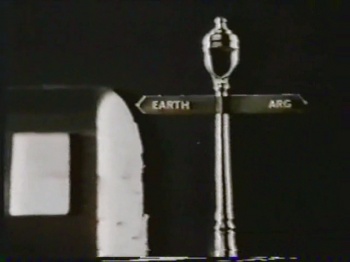

Structurally, The Adventure Game followed the basic plot laid out by the computer game Advent and its many derivatives. There was a prologue, an initial test that would help the explorers to make sense of the world around them, and introduce them to some element that would recur during the show. The traditional middle game was collecting treasure and moving it somewhere else: on television, it became a question of opening a locked door through a simple task of trial and error. Advent concluded with a "Master Game", with such elements as secret canyons, wizards' houses, trolls on bridges, volcanos, silver bars, magic rings, and lamps with limited battery power. For the television show, these became a challenge to get through another locked door, or win a crystal, using the laws of physics, often by using elements of history, sometimes some code-cracking, and oodles of lateral thinking. What set The Adventure Game apart from every other interactive fiction game made up to this date was that it was written with wit and humour. The computer games packed as much game as they could into the limited space available. Anything that didn't advance the plot was rooted out as a waste of space: the austere Advent's one nod to humour was calling a cave "Witt's End". | |

| Furthermore, The Adventure Game wasn't restricted by the verb-noun instruction set of the computers, and could operate at the level of natural language. Even thirty years later, computers can't talk as well as humans all the time. There were pieces of whimsey that were unique to the culture: anagrams of "dragon", clues scattered throughout the show that led to the same conclusion ("we're not going to tell you the password is 'wisdom'"), motifs that came back during an episode and throughout the series. Indeed, the 1981 series was introduced by a brass-band interpretation of a Grieg piece that Dowling had used in The Railway Children a quarter of a century earlier.

The Adventure Game both needed and was able to go further than the traditional three stage game, adding an all-or-nothing denouement suitable for television. From the second series, Dowling came up with The Vortex, loosely based on Hnefatafl, the favourite board game of the Vikings ten centuries earlier. Even if children didn't fully understand the puzzles in the master game, they would enjoy the guesswork of the finale, and rejoice when Noel Edmonds got deaded by the Rangdo. The Adventure Game won the Harlequin Award for Drama and Light Entertainment for its second series in 1981. The Adventure Game would go on to inspire the authors of computer games, and begat the interactive fictions of Knightmare and What's Your Story?, and latterly programmes like Time Busters. Even Raven owes something to the Argonds: they demonstrated that viewers will accept their representatives intruding into a recognisable fantasy world. A games exhibition in Birmingham earlier this month featured a Living Dungeon challenge, which cited all of these shows (and The Crystal Maze) as inspirations. | |

| Dowling retired in 1982, and briefly moved to Australia, where he lived in such a remote place that he didn't even have over-the-air television. He returned to the UK, and consulted on the last two series of The Adventure Game. By now, other projects he had started were coming to an end: Take Hart was replaced in 1984 by Hartbeat, in which Tony shared the limelight with other, younger, artists. Jigsaw came to an end in 1984, while Why Don't You ran until 1992. Sylvester McCoy and Russell T. Davies would both follow Patrick Troughton to Dr Who. Sproxton and Lord founded Aardman Animations, purveyors of fine animated characters with a fondness for Wensleydale.

Patrick Dowling remained active into his eighties, giving interviews to researchers and helping his colleagues to keep memories accurate. Dowling died on 17 June 2009. In researching this obituary, we have drawn heavily on an interview Dowling gave to Off The Telly in 2004; the It's Prof Again website for its history of Vision On; and the Inform Fiction history of interactive fiction. All errors of fact and interpretation are our own. |

This Week And Next

With neither Apprentice nor Talent, ratings for the week to 14 June showed that it's summer. HIGNFY led the game show front, with 5.85m seeing the Friday show, 2.45m the extended BBC2 repeat. Celebrity Masterchef was seen by 4.15m, with Mr and Mrs and Millionaire both recording 3.9m. Big Brother's best audience of 2.9m came on Friday, while 8 Out of 10 Cats was seen by 2.65m.

Come Dine With Me led on the digital channels, 1.08m saw the repeat, and that's the highest audience of the year. America's Got Talent was knocked into second place with a "mere" 1.05m. ITV2's acquisition of I'm a Celebus began with 560,000 viewers, but shed them as the week progressed. Big Brother's Big Mouth was seen by 450,000.

Highlight for this week is The Chase, which seems to be a cross between Weakest Link and Eggheads (ITV, 5pm weekdays). On the digital channels, Shooting Stars comes to Virgin 1 (10.10 Saturday) and UKTV Watch has Hole in the Wall and Strictly Come Dancing (Friday from 8pm).

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers sign up to our Yahoo! Group.