Weaver's Week 2012-01-22

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

Contents |

The Bank Job

Remarkable Pictures for Channel 4, 2-7 January

New year 2012, and there's still a camp outside St Paul's Domed Tourist Attraction. A couple of hundred hardy souls bear witness to what they see as the sins of the City of London Corporation. It doesn't publish its accounts, it employs its own private security service, the tentacles of the City Corporation reach into everyone's life, and it's not democratically accountable for any of its actions.

Five hundred yards in a broadly easterly direction, past the iron fences preserving the fantasy of those who would claim to own Paternoster Square, down Cheapside and Poultry, brings us to a glorious building, stone pillars and high windows. It's one of Edwin Lutyens's finest designs, from an age when banks were secure and respectable institutions, for it was the headquarters of the Midland Bank. Abandoned by its new owners, the building has been refurbished for use in film and television work. This week, it's being occupied by Endemol's latest production for Channel 4.

On the street outside, four cars are drawing up, each to disgorge a sharply-dressed twentysomething. They all entered and succeeded at an online game, and are here to try and win a stonkingly large amount of money. According to Radio 4's More or Less at the end of last year, a personal income of £170,000 is likely to be amongst the top 1% of all incomes this year. According to show host George Lamb, all of the money found by the daily winners will be won.

The game itself was simple to understand. George will ask some questions. Get one right, and a player is allowed to request that one of 25 numbered bank vault boxes is opened. Inside that box may – or may not! – be some money. And it's real money, in real used £20 notes, neatly counted and labelled. If there's money, it's put into the player's suitcase. The player can then leave, avoiding the risk that they would be caught in the vault when the limited time ran out. If all players left, the one with the smallest stash lost.

There were some slight changes for later rounds. The middle stanza gave the contestants two cases, but only allowed them to put one bundle in each case, and sealed cases couldn't be re-opened. Contenders were allowed to reject amounts they believed to be insufficiently large. The final round used a chess-clock principle, either one or the other player would be counting down during each question.

Open the box! Take the money! Never mind Take Your Pick, do both!

Open the box! Take the money! Never mind Take Your Pick, do both!

The game, then, was simple enough to be understood by anyone. But these skeleton rules hid some large loopholes, inconsistencies that could appear to favour one contestant. Not explaining that players could only leave the vault when they get a question right, we can almost put that down as a first-night oversight. It was the rule in the qualification process, the opening to the show had suffered from a Technical Fault caption, and things looked flustered. But it meant that viewers who hadn't played the online game – and most of the viewers won't have played the online game – were being denied a critical rule.

That we could forgive. We cannot forgive the inconsistent treatment of boxes containing zero pounds. In round one, a player can leave after opening the box, even if they find nothing. In round two, a player cannot leave if they answer a question correctly and find nothing. It's not tremendously difficult to be consistent: either a player is allowed to leave on a correct answer, or they must give a correct answer and find some money. This doesn't need to change from round to round.

It certainly doesn't need to change within a round. Having introduced one new rule (that an error on the question being asked as time expires invites a new question for the opponent), the producers modified another one, that this question had to be answered correctly and find money to allow an exit. That clearly altered gameplay.

Even within a round, this inconsistency altered gameplay: with time running low in one day's middle round, contestant C elected to retire on £15,000, behind rivals D and only just ahead of E. C knew that D had to get one of three remaining questions right, and find money, to get out. If the opening round rules had been in force, D would have been able to retire on no money and be assured of a place in the daily final.

So far, The Bank Job was coming across as a yacht with small holes below the waterline: however good it looks on the surface, there's a lot of work below decks to keep up appearances. And appearances are what matter: none of the players could have been much older than 30, all were conventionally good-looking. It represents the viewers Channel 4 wanted to attract, but it surely doesn't represent the viewers who were actually sitting down and watching the programme, or even those competing for the prize. Such unbalanced contestant selection must surely raise questions for the regulators, the arms of society charged with interfering in the corporate world's aim of making as much money for itself as possible. So must the method of applying – an online-only entry is quite deliberately designed to exclude the old, the poor, those without much time.

Host for the week was George Lamb, who has long annoyed us with his ability to secure high-profile media work without actually being any good at it. He tries, goodness knows he tries, but his efforts always come across as patronising. He can't do accents, and causes offence when he lapses into what's meant to be an Ulster tone. He doesn't tell jokes, efforts fall flat. He can't remember names, unless people are all called "mate" and "man" and "buddy".

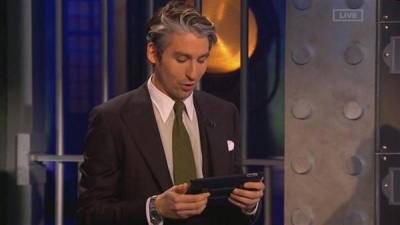

Lamb's many limitations were shown up by the utterly bizarre decision to make The Bank Job a live show. There was no need for this, unless the Endemol division really wanted to trumpet its own ability to promise more than it could deliver. As we discussed last week, in 1995 Bob Holness had found that a wireless link to the question computer wasn't going to deliver questions more reliably than a traditional file card. In 2012, George Lamb found that a wireless link to the question computer was going to break down, typically about once a night, causing a short pause while he swapped one tablet for another, and quite possibly resorted to an emergency supply of file cards.

Even when the technology was working, very little else was. The clock would start and stop of its own volition, causing further hold-ups while it was rewound. It wasn't until Wednesday that it became clear the show used Mastermind rules: the question in play when time expires is completed. Judging was imprecise, with expanded answers sometimes accepted and sometimes not, apparently at the whim of the producers.

There was no reason for this programme to be live. The host made no references to any viewer activity during the broadcast, and there were no captions during the programme proper, though some were aired while a commercial break played in the bulk of the screen. Going live added nothing to the spectacle, and seeing the mechanics exposed to the world allowed viewers to concentrate on the mechanics, and not what was actually going on. It would have been a better show if taped in advance, even by just a few minutes.

For inside this Lloyd's Building of game shows, there was actually a very good game. When it came to a crunch, when two players made a reasonable effort to compete in the final, the show produced exceedingly high drama. The setting served to enhance – players in a real bank vault, behind real steel bars, security guards handling real money, and only opening the huge vault door when someone was about to pass through it. We could have lost the strobing before every question – that got very old, very quickly – but the rest of the set design was wonderful. Even Marc Sylvan's music was a cut above.

And then we come to the grand final. Five players, reduced to three via the usual daily rounds, and to two by the first daily round. Yes, the game played in the online applications appeared in just 5 of 19 rounds played on screen.

Throughout the week, George Lamb had been valiantly trying to come up with a viable catchphrase. "We'll put three seconds back on the clock," seemed to be the early favourite. "Could you move it down?" and "Let me just change tablet..." were also contenders. Eventually, "Get rich and get out" emerged as the show's motto. Our two finalists had got rich, and got out, and survived six rounds, and had contributed towards a £467,500 prize fund.

There are many possible ways of awarding this money. This column's preference: play to a winner, then split their winnings between nine boxes. Ten questions, one minute, something in each box. The choice is open the box or exit. Whatever's left in the vault is split between the other finalists.

But no, the producers saw something that has never worked on television, and tried to make it their own. The producers decided to re-enact the final of Shafted. To repeat the final of Golden Balls. They let the finalists address each other, and to decide whether to share the money, or to try and shaft each other out of it. It's entirely unclear how this meets with the claimed theme of "get rich and get out". It's very clear how this meets with the show's real theme, "we don't know what we're doing".

The Bank Job is a parable of our times. It is an undemocratic institution – it pretended to allow everyone to apply, but anyone who looked over 30 was never going to get on. It manipulates its contestants, telling them that Remarkable Pictures knows how to make good television; and manipulates the audience, saying that a knowledge of entertainment trivia is all one needs to be a success. It expects to repeat its mistakes – already, we hear that a second run begins in mid-February, before we've properly digested the lessons from the first series.

It features a private security service, "guards" looking after the money, and looking after the host, with no duty to the viewer or player. Only the guards and the host were ever allowed to handle the bundles of cash, the contestants never got to touch it at all. And it told us that poverty is the result of someone's own bad decision: it left us with the clear message that the two finalists *chose* to leave with nothing, the fact they're not applying for membership of The 1% is entirely their decision.

People in a bank, looking out for themselves, keeping their own "security" staff to evade the rule of law, punishing people economically for the selfish decisions of others, and seeking to prevent the spread of infectious ideas other than their own. The City of London in 2012.

University Challenge

Group phase, match 4: Clare Cambridge v Homerton Cambridge

Clare Cambridge were barely troubled by Leeds in their match on 24 October; Homerton really had to work to beat Durham a fortnight later. Our money's on Cambridge to win.

We'll begin with Faint Eurovision Reminder of Last Year, a series of definitions all heading to the answer "Blue". And not, as one contender suggests, "Scrapie". That's one for the Failblog, as is Homerton's recollection of the losing party in Ireland's election last year, Fianna Fáil. Clare promptly get another starter wrong, not recognising a particular king's lineage.

Things do get better, Homerton prove very handy on various scientific diagrams, and get the first visual round – it's a list of works by one particular author, but presented in anagram form. Nasty to answer, but a lovely question for the viewer. Homerton's lead is 80-10, and falling, though not before Clare manage to suggest that "Papuanewguinea" has a sense valid in Countdown (and other, less popular, word games). They were, of course, thinking of "guinea".

Speaking of other game shows, we wonder if Mr. Paxman is auditioning to host the proposed new version of Blockbusters, because his tie clearly shows some hexagonal patterns. That brings us to the audio round, some opera, but no-one knows the composer's Offenbach, and presumably often away, and Homerton leads 90-40. There's no Only Connect this week, but we do get a "whaaaa..?" moment, as Thumper tries to get the contenders to continue the Fibbonaci sequence transliterated into the Roman alphabet, so "A A B C E H" is (obviously) followed by M. No, us neither.

Here's a question we liked: What part of the psychic apparatus devised by Freud is an anagram of the Roman numerals for the number 501?

Why is this good? There are so many ways into it: the psychology, the etymology, the wordplay, and quite simply there aren't that many anagrams of DI. We're up to the second visual round, asking for a specified child of various royal parents. That falls to Homerton, whose lead has been trimmed to 115-90. Cities in Brazil lead to questions on chromosomes, and that allows Clare to tie the game with about five minutes to play.

Game on! Clare score with authors whose initials were "GG", and do well with questions on Lancaster. Which country's hosted the Winter Olympics the most? The Yankees, surprisingly. Which drinking organisation — well, it's got to be CAMRA, but Homerton don't do well on places named in literature. Five points, 2.5 minutes, and Clare score with a description of Washington DC, and some questions on sugar that our host doesn't understand.

Homerton need this. How many days in the first three months of a leap year? Homerton have it, and bonuses on Welsh food. They pull to within five. It all comes down to this, a question on malaria. Homerton pick up a missignal, but Clare fail to convert. Another question, on religion, that does go to Clare, and part of a set of bonuses on woods is icing.

Clare win the contest, 170-145. Both sides gave 25 correct answers, Clare from 50 questions, Homerton from 52. The difference was in the incorrect interruptions: Clare lost just five points to this error, Homerton dropped 25.

Next match: UCL v Pembroke Cambridge

Mastermind

Heat 9

Dum-de-dum-de-dum-de-dum. Kate Foley begins things tonight, taking The Archers (est 1950), a daily documentary about life in a rural village. Recorded on the day of transmission, and edited down in real time, it's paved the way for scripted fly-on-the-wall series, of which more next week. On the Celebrity Mastermind series, Jacqui Smith proved to know a lot about the village, but then she was standing for election as its MP. The round perpetuates the BBC's convenient myth that it's all a work of fiction, asking about "actors". Cuh. The final score is 7 correct (4 passes). Read more: who are the participants?*

Paul Radford takes The Apollo project (1961-75), charged with putting a man on the moon, and returning him safely to earth. The basic idea was to fire a rocket to the moon, then use a separate vehicle to achieve touchdown, and then come back. The project built the ginormous Saturn V rocket, and met with triumph (Armstrong's landing), tragedy (three astronauts killed in tests), and ennui (who remembers the 12th man on the moon?) 12 (2) is the result. Read more: pocket guide to the moon landings*

Mark Wyatt covers the Life and Music of Nick Drake (1948-74), a folk musician active in the late 60s and early 70s. He recorded three albums, critically acclaimed but commercial failures, suffered from depression, and died mysteriously. Drake has been cited as an influence by Peter Buck, Paul Weller, and Elton John. We have a round that neatly covers Drake's life, in approximate chronological order. And we have that rarity, something worth celebrating, a Perfect Round. Eighteen questions, 18 correct answers. Listen more: Drake's "Five Leaves" album*

Chris Forse is taking the Cold War 1946-64. This was a long stand-off between forces loyal to the USA and those loyal to the USSR, two implacable rivals who assured each other of nothing more than destruction. Eisenhower and Kruschev were the nominal leaders, we perhaps remember their successors JFK and Brezhnev. 15 (0). Read more: book of the BBC's landmark series*

Kate Foley is back in the chair. She knows the apocryphal tale of Peter Mandelson confusing guacamole and mushy peas, but doesn't remember using chat rooms on the internets. She's far too young to remember those! Her final score is 19 (6).

Paul Radford knows the definition of a pork scratching, and where to find the Caribbean Sea. Since this show was recorded, Alan Titchmarsh has moved on from Radio 2's Melodies for You, the creator of Dalziel and Pascoe has died, and television has been broadcast in colour. A final score of 21 (7) there.

Chris Forse is back. Six will give him the lead, realistically he needs a dozen to try and survive the repechage board. The tactic is clear: if he thinks he knows, he'll guess the answer, otherwise he'll pass straight away. So the colour of the saffron flower and the next province to Labrador get an answer, but a folk song of the 15th century gets an instant pass. If it helps him to squeeze in a couple more questions, it'll be worth while, and John Humphrys begins a further question right on the buzzer. Final score of 26 (8) is certain for the repechage board.

The repechage board:

- John Marshall 31 (5)

- John Snedden 30 (4)

- Paul Smith 28 (3)

- Chris Forse 26 (8)

- Jeff Grimshaw 25 (4)

- Hannah Jones 24 (5)

- Isabel Morgan 24 (5)

That's unless Mark Wyatt can't dredge up nine correct answers in the next 150 seconds. The dog collar, Camelot, the mute swan, and he's already a third of the way there. Emulsifiers and Guns n' Roses, they provide correct answers, and though the pace slows down from its frantic start, he still passes the winning mark with a minute to spare, and closing on 31 (2).

This Week And Next

We were surprised to see a major star appear on Who Dares Wins last week. Partnering sprinter Montell Douglas was that star of films like Beverly Hills Cop, young Eddie Murphy. He's not quite how we remembered him, but then time does that to people. Anyway, he and Monty won one, split £25,000, and then lost the next game.

Reality television is eating itself. That's the conclusion after watching this week's Blue Peter, in which Stacey Solomon (The X Factor, I'm a Celebrity) gave tips to Sam Nixon and Mark Rhodes (contestants in the current series of Dancing on Ice). But wasn't Sam & Mark formed when the pair met on Pop Idol, back in 2003? Ah, there's the rub. For the target Blue Peter viewer, Pop Idol is ancient history, a forerunner of The X Factor hosted by those guys off of Britain's Got Talent.

Ratings for the first full week of the new year are out, and Dancing on Ice skates into the top position, 8.4m people saw the early performances. 5.9m saw the return of Who Dares Wins, and 5.35m Celebrity Mastermind – the part-networked civilian version on BBC2 attracted 1.9m viewers. Take Me Out, that was seen by 4.95m, with 845,000 following the show to ITV2. Celebrity Big Brother returned with 3.5m people asking "Who are these people?" University Challenge was seen by 2.85m, QI by 2.55m, and Eggheads by 2.45m. A slight return to the mid-90s, as Channel 4's top game show was Countdown, 2.5m saw the game played by a bunch of sexists. The rest of the night pulled around 1.75m, that the score for Come Dine with Me and The Million Pound Drop Live Not Live. Missing from Channel 4's top thirty was The Bank Job, it didn't exceed 1.6m people in its one-week run.

Got to Dance remains the top digital game show, 1.035m for this week's auditions. The Only Connect CoCoC had 760,000 viewers completely dumfounded, and we can compare Bit on the Side between Channel 5 and 5*. Just over a million on Channel 5 on Thursday, barely 245,000 on 5* Sunday. Still better than The Devil's Dinner Party (100,000 on The Atlantic Channel).

A very quiet week this week, and we've actually failed to find anything new this week. It is the end of Celebrity Big Brother (C5, Friday), which means we'll have some short notes from the laboratory next week. Er.... Come Dine with Me in Ipswich (C4, 5.30 weekdays), and Masterchef continues (BBC1, Tues and Weds).

Links marked with a * help support the UKGameshows servers.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.