Weaver's Week 2020-03-29

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

This week, we go back almost twenty years. It's a time when the host was in one room, bars separate him from the contestant, and all the other players were ensconced in their homes...

Paranoia

Triage Entertainment for Fox Family Channel, 14 April – 7 May 2000

Back at the turn of the century, the great hype was Interactive Television. Our show begins with host Peter Tomarken explaining how to play by telephone, "call 1-87-paranoia", which is great for people whose keypads have 36 numbers and letters. Or you can play on the Internet, paranoia.excite.com the website you wanted.

Why would you want to do this? "You can make our studio player paranoid," in some strange way that isn't properly explained. Apparently, our player can potentially win 1.5 million dollars (then about £600,000 after tax; now worth about £1.2m). The actual average prize is likely to be a fraction of that peak, but "Our player's likely to win two years' wages" is always a big-money claim.

The first gimmick of Paranoia came in the staging. Both Peter and his contestant Steve are in small cages, like baby's cots. They're on the end of extendable poles, and raised above the ground. With a backdrop of computer images (because this is the year 2000 and the future is here now!), the show looks like nothing else on television.

And, indeed, it looks like nothing before or since: the stabby synths and the purple colour palette put it clearly in the shortlived "Future Now" aesthetic.

The future is indeed here now. While we've been talking to Steve, the Internet has been voting. They've picked three from a number of "satellite players", people who are sitting in their homes – or out on the university grounds – with a satellite truck beaming a signal up to the studio. These three people are out to pilfer Steve's money

Steve, our studio contestant, has been given $10,000 in used banknotes. Ten bundles of a thousand each. He'll be asked a series of general knowledge questions, with four possible answers. Get it right, wonderful. Get it wrong, he has to hand over $1000 cash.

And there's more. After each question, Steve has to challenge at least one of the "satellite players". Absolutely must do it. Should the person he challenges have got the question right, Steve will give $1000 to that player. If they've got it wrong, they'll be given a "strike"; a second "strike" will force the player out of the game, and they'll leave with whatever money they've won from the challenges. Steve's got the option – but not the obligation – to challenge two or even three satellite players on each question.

Steve has two lifelines, but they come at a cost. "Swap out" allows Steve to remove one of the satellite players, and replace them with someone else – chosen by the Internet. This costs $1000. "Knock out" lets Steve give two "strikes" to any satellite player, eliminating them from the game entirely. This costs $3000.

Was Paranoia the first game show to measure lifelines in wodges of used bank notes? We thought The Million Pound Drop invented that idea. And, for our money, Paranoia is just as good a game, whether played live or on tape.

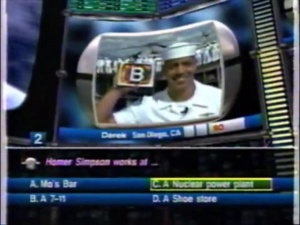

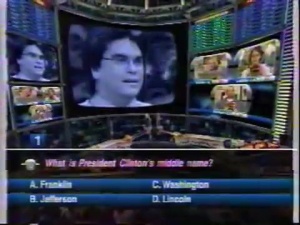

Note how answers A and B are on the left of the screen, unlike other shows. The satellite players are in the three boxes to the right.

Note how answers A and B are on the left of the screen, unlike other shows. The satellite players are in the three boxes to the right.

The questions aren't terribly demanding at first – "what is president Clinton's middle name?". We see that there's very little delay for the satellite players, normally we'd expect a bit of a satellite delay between the studio and the players in Chicago or Louisiana. Were they using fibre links? And we see the satellite players identify their answer by a very low-tech method: they hold up a card and turn it round when asked.

Peter Tomarken is the host, he keeps up a strong patter and ensures the show moves on well. He knows the format inside out and always sounds in command of the situation. Peter's best remembered as the host of Press Your Luck, but more on that in a few weeks.

By question five, we've got the question "What did Famous Amos do for a living before he baked cookies?" That's a really tough question, pretty much everyone guessed. Steve can – and does – challenge more than one player, and gets lots of strikes.

From time to time, host Peter will go to the "folks on the Internet and the phone". There are five players on each platform, changing for each question. These players chisel away at a cash jackpot. It starts at $5000, and every correct answer from the phone and Internet players robs $50 from the pool.

Eventually, Steve knocks out all three players on the satellite, with $2000 left in cash. The "interactive jackpot" still stands at $3900, four questions unused plus many errors from the phone and 'net players.

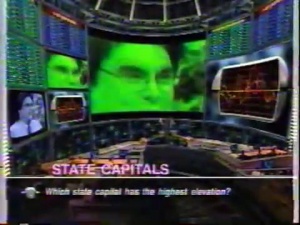

Now we get to the bonus round, Steve picks one of ten esoteric categories from a board. "British theatre", "state capitals", "children's literature", and many more. A correct answer to this one question will multiply Steve's winnings by ten – or, by picking one of the categories assigned by the producers, will multiply his winnings by 100. A wrong answer will leave the winnings unchanged.

Yet another gimmick enters the mix here: Steve's heart is pounding. He's been wearing a microphone on his body, picking up the pounding of a nervous man's heart. It's a gimmick, they use it to provide ambient tension, and don't overuse it like The Chair with John McEnroe.

This sound does overshadow a really creepy soundtrack, goth-laden synthesised strings and other metallic chimes of doom throughout the show.

And there's more: Peter is going to give away a new PC from the sponsors to someone playing along at home on the Internet. So he calls up their webcam... ah. The webcam has not yet been invented. Calls up their phone? No, this is an Internet player. Peter's going to use text chat.

Fortunately, because it's a multiple choice question, the player at home only needs to type one letter on her keyboard. It keeps the game flowing well, and looks good on screen.

Peter also has a talk with a phone contestant, represented by a spiky sine wave.

And so we go on, usually squeezing two full games into the hour-long show.

Behind the scenes, there's another game being played. The Internet players are tapping out their answers, and the best will be allowed to enter in the pool to become satellite players in a later show.

Paranoia intended to make contestants think they were running out of money, and running out of time, and ramped up the pressure. Peter Usher devised the format, and also produced the show

Paranoia put out episodes on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, but only lasted a month. There were lots of little problems pulling against it, beginning with the four time zone thing. Early evening primetime 8pm in Delaware is 5pm in Oregon, where they're still at work. Though the weekend made it easier to schedule, Paranoia couldn't completely overcome the problems of geography.

Nor could it overcome ratings: good, but not stellar. Intended to sell Fox Family's specials – a concert by *N'Sync, drama series Higher Ground – our show didn't quite put eyeballs on seats. ABC's decision to schedule Who Wants to be a Millionaire opposite the Friday show really hurt.

It's a shame, because hindsight shows how Paranoia was one of the few good shows to come along in the wake of Millionaire. After two decades, we can see the game remains solid, there's always some reason for the studio player to keep playing, and tension remains right to the end. Peter Tomarken is a consummate host of live television, he's got the same unflappable vibe as we got from Bob Monkhouse then, and get from Dermot O'Leary now.

None of the key players are around. Paranoia lasted these four weeks. Higher Ground lasted its 22 original episodes and then vanished, though alumnae include Anakin Skywalker and Kaylee Frye. Fox Family was bought up by the Walt Disney company in 2001, and renamed ABC Family. Peter Tomarken died when his private plane crashed in 2006.

And that's Paranoia, the show where (almost) everyone plays from the comfort of their own home. While almost all of the shows are up online, we sense a revival could be imminent.

In other news...

Congratulations to Singers on Buzzers, the series winners of Jon Snow's Very Hard Questions on More4. It's clear that when played well, by teams who understand the clues and how to use them, Very Hard Questions can almost be entertaining. It's still clear that Jon Snow still sounds like he's reading words appearing in front of him, and lacks the natural spontaneous wit of other hosts.

We're sorry to report the death of Bill Martin, composer and songwriter, at the age of 81. He leaves us with such anthems as "Puppet on a string", "Congratulations", "Shang-a-lang", Slik's "Forever and ever", and 1970 football song "Back home". His most lasting contribution to culture might be the 1983 musical Jukebox, melding various people's songs into one semi-coherent story; it's the trope namer for the Jukebox Musical genre.

On the webs, Amelia Tait of Vice has analysed lots of episodes of Come Dine with Me, and found the perfect recipe for a dinner party. The most popular starter surprised us.

Film Stories offers some memories of Cheggers Plays Pop, the show where Keith found his vocation.

The latest postponement: Bake Off, the main civilian series. Normally filmed from late April to early July, this year's series may yet make its traditional late-August start.

Predicting schedules is difficult at the best of times, made even more difficult by the current events. The big mystery is where new Pointless will show (weekdays, BBC1 or BBC2 – probably!) Caru Siopa (S4C, Mon) revives charity shop finds, and Have I Got News for You begins its 30th year on air (BBC1, Fri). BBC2 wraps up another series of Only Connect (Mon).

At the moment, next Saturday includes the Celebrity Mastermind postponed from last weekend, In for a Penny in Bristol, and new Catchpoint. What will air? Place bets now!

Photo credits: Triage Entertainment, Youngest Media.