Weaver's Week 2022-05-01

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

In an average week, television has about 500 game show episodes. Some of them are niche programmes on obscure channels, like The Remotely Amusing Game Show on BBC Scotland. Many of them are repeats, usually of The Chase on the Challenge channel. A few of them are first-run shows. Got Talent always pulls in big numbers, and Have I Got News for You remains popular amongst pro-establishment viewers.

New to the top five of the chart, firmly in the top 1% of all game show episodes, is

Contents |

The 1% Club

Magnum Media in association with Silver Star for ITV, from 9 April

It's an unlikely success story. Lee Mack has never hosted a primetime ITV show before: indeed, the last time we remember watching Lee Mack on ITV was The Sketch Show a couple of decades back, and that got cancelled while we were still chuckling. ITV's record with unashamedly intelligent programmes is variable, just ask The Krypton Factor.

And yet The 1% Club has pulled in viewers by the busload: four million and more, last time we looked. What's the secret of its success?

"Forget about exam results, tonight is about how your brain really works." It's a quiz, except it's not really a quiz, only it is a quiz. "Our questions test logic and common sense." And there's a big prize, up to £100,000.

Lee gets the show moving very quickly. In less than 50 seconds, we've had the dramatic opening, Lee's explanation, and the opening title. (Or, on the first episode, a shot of the arena where the opening title would have gone. We meticulously spot the errors in 0.1% of the show.) While some programmes are still pratting about in their three-minute opening recaps, Lee has given us an example question, and is talking about it to some of the 100 players.

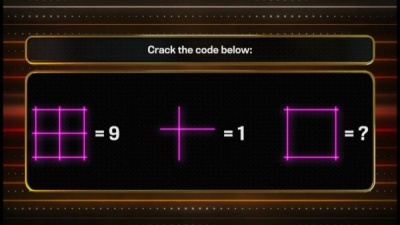

The questions on The 1% Club are braintwizzlers, questions of observation and patterns. They're designed to require little outside knowledge, nothing more than the alphabet or numbers.

Each question has been asked to a group of online survey takers. Some of the group got the question right, some of them got it wrong. From this information, they're able to work out how many people in the country would get the question right. The easiest question is a 90%-er, answered by 9 people in 10. The most difficult, at the end of the show, is answered by just 1% of the people. Get this right and you're in the 1% club.

Does this sound familiar? A bit like a Pointless road trip, a journey down the column, stopping off every now and then for a question? Folk with a really long memory will remember Beat the Nation on Channel 4 a couple of decades back, that show asked general knowledge trivia to test the nation's abilities. The show – hosted by Graeme Garden, with Tim Brooke-Taylor as the richardosman – ran for just one series in 2004. Ripe for a revival, if any channel's looking for a 30-minute show around teatime.

But back to The 1% Club, at the heart of ITV's Saturday night schedule. After the example question, with Lee Mack making an example of the one person in the crowd who got it wrong, we're into the game proper. Who is in it to win the £100,000, and who thought they were going to see Jane MacDonald?

Ah yes, the £100,000. Each member of the studio audience has £1000 to their name. For now, it's not actual cash, just an imaginary bit of coin. Should a contestant get a question wrong, they're out of the game, and their £1000 goes into a communal prize pot. At the end of the game, the last players standing compete for that prize pot. Lee bangs on about this prize pot at every opportunity, because it gives The 1% Club a chance to be a Big Money quiz.

So, we start with a 90% question, one that the vast majority of people got right. Which of these photos has to be wrong? A tiger in a stream. A polar bear in the desert. A gorilla in the jungle. The players in the studio have 30 seconds to answer. For the viewers at home, we get 23 seconds of thinking time, during which Lee Mack delivers a one-liner. Almost all of his jokes are funny.

Have we lost anyone? We have. Oh, sorry about that. They're throwing a party in your honour down Whitehall way. It's all fine.

The show continues in a similar vein, with an 80% question, a 70% question, a 60% question, and a commercial break. Sure, 30 seconds is a long time to work out which of "Singular", "Unique", and "Individual" doesn't repeat a letter, but the show wants as many people to stay in for as long as possible. Lose too many people too soon, and Lee will have to fill with his famous tap-dancing routine.

To help keep people in the game, a new rule comes in. Starting with the 50% question, players can use their £1000 to buy a pass. They don't have to answer this question, and remain in the hunt for the overall win, but their money is transferred into the big prize pot.

And the questions keep coming. "If planet 'Earth' has a 'heart', which body parts does 'Mars' have?" Yes, they allow free responses to these questions. Everyone's been given an ITV computer tablet, and can tap out their answer before pressing the big "Confirm" button. Everyone who put "Arms" – the answer the producers expected – will go through. But so will anyone who gave a different answer and can argue their reasoning to the satisfaction of the independent adjudicator – and independent adjudicators are notoriously hard to satisfy.

Checking all of these answers can be a long and laborious process, because big money is at stake – it's not like Ash the Bash and a friendly game of [redacted]. We were sorry to hear about some horrifying practices at the recording session – people being kept in their seats for six hours or more, not even allowed a toilet break without a runner shouting at them. Nor did the producers provide any food or drink, it's no wonder the contestant who brought a pack of cheesy Wotsits had eaten them.

Another criticism of production: there are now three classes of people in the show. Those who are still in, illuminated by a bright white light. Those who are now out, dimly lit by a dark blue light. And those who have paid for a pass, lit by a lighter blue shade. We just about see the difference while they're spinning lights during the thinking time, but not in audience close-ups while they're discussing the answers. Contestants have pointed out that these individual lights are hot, and shining almost directly in the face, which isn't at all comfortable. Could they have small LED panels by the contestant's head: bright green while they're in, black when they're out, a medium blue after they've paid for a pass?

Anyway. The show continues, after 50% they go to 45%, 40%, and down in 5% steps. Lee Mack presents in his own style: appears to make a condescending putdown, then undercuts himself, and praises how well the contestant's done. He's endearing and reassuring and supportive, and it does bring out the best in the contestants.

At the second commercial break, the remaining contestants have a decision to make. Anyone who has got everything right, and hasn't spent their £1000 on a pass, is entitled to take the money right now. They'll leave the game, no longer be in contention for the top prize, but they'll be assured of something. It'll help pay the transport costs and car park fees, something else not met by the production company. This opportunity to take the money won't come around again, it's literally now or never.

Some of the questions are not as precise as they might be. "If Jack turned 17 yesterday and he'll turn 18 this year, what date is his birthday?" They're expecting "31 December", though any New Year's Eve would surely pass the independent adjudicator's steely stare. So long as there's a competent adjudicator, the show will be fine. Most of the questions are fine, as we'd expect from the gamekeepers and setters behind Only Connect.

As the game goes on, there are fewer players. Lee starts to talk to everyone, especially when we're down to five players at the 20% level and there's a serious danger of the show under-running. Lee really doesn't want to dance above the ITV washbasin.

Eventually, we get to the 5% question. The players still in after this are our winners – and it can be just the one winner. Anyone who didn't use their pass has kept the £1000, and will take it no matter what happens. (Reading between the lines, we think it's possible for the game to end messily, if everyone gets the 5% question wrong we assume those who were still in after 10% become the winners. Hope this doesn't happen too often, or that Lee's prepared a speech as memorable as Michael McIntyre's.)

Our winners have a decision. They can leave the game, and there's £10,000 to be split between players who leave right now. (What if two leave and one stays on: do the leavers get £5000 or £3333? We don't know, this isn't clearly explained and didn't happen in the first few episodes.)

Or the winners can stay and face the 1% Question. We've been leading up to this for the last three-quarters of an hour. It's a question only 1% of the survey got right, it's seriously and properly difficult. Anyone who gets this deserves all of the riches in the world. And anyone who has got here without using their pass may as well have a go.

The 1% Club is a properly difficult quiz. It finds worthy winners, everyone who gets to the final has got a dozen and more questions right, most of them defeat most of the populace. Lee is funny without being snide, he's the antidote to Jimmy Carr's cold and uncaring schtick. The music is upbeat and brassy, Twin Petes have built from their hook.

There's a clear playalong game: how far would you get at home? There's smug satisfaction in wondering "how did 80% of people not know that?" and the satisfaction of seeing a difficult puzzle explained. (For the record, this column has played along according to the rules. We've made the show final once, and left at the 5% question twice. Only once could we have taken the £1000.)

We very much hope that production have learned from the opening series. Treating contestants like cattle really isn't acceptable, we would be very pleased to hear that series two is much slicker.

It's clear that The 1% Club has hit a chord with the watching public. Almost 10% of the population have seen some of the show, and it's been bossing BBC1's high-profile drama Killing Eve in the ratings. As seen on screen, The 1% Club is friendly fun, we can feel smug as we beat the players, and get properly invested in the real people's drama.

There's a market for relatively difficult quizzes, so long as they're presented in an accessible way. Where does The 1% Club owe debts? To Pointless, to Beat the Nation, to the massive multiplayer games 1 vs 100 and All Together Now. Mostly to Only Connect, which demonstrated that wit and charm can help viewers enjoy the most difficult content. OC took about fifteen years to become television's top quiz, The 1% Club has just gone straight into pole position.

The 104% Club

The zombie proposal to sell off Channel 4 absolutely refuses to stay dead.

Much nonsense has been spouted in favour of this ludicrous proposition, not least that Channel 4 is the current government's to sell. The DCMS asserts that it owns the corporation, but is unable to produce any supporting documents. We are unable to trust anything said by a Whitehall department without corroborating evidence.

Channel 4 is the only money-laundering operation to actually benefit society. It takes in a thousand million pounds of advertisers' money. It spends a thousand million pounds with television and film makers, creating many thousands of jobs that wouldn't otherwise exist. Many of those jobs are in places ignored by the current government; almost all show creative skills. And the result of this effort is beneficial to society.

Yes. In the reverse of what normally happens, Channel 4 turns advertisers' money into something good for society.

Lego Masters: Richard Osman inspects a fairground.

Lego Masters: Richard Osman inspects a fairground.

Channel 4's mission – defined in statue – is to make "a broad range of relevant media content of high quality that, taken as a whole, appeals to the tastes and interests of a culturally diverse society; high quality films intended to be shown to the general public at the cinema; the broadcasting and distribution of such content."

The Channel 4 company is expected to make neither a profit nor a loss, and has near-complete latitude to pursue other activities to support its broadcasts. Spin-off channels like More4 and E4, timeshift 4seven, niche channels like 4Music, all make a profit to support the core activity. At one point, Channel 4 planned to own a digital radio multiplex, which is completely in keeping with its objectives – Channel 4 commissions media content, which includes radio.

"Taken as a whole" is important. Some of the most full-of-themselves blowhards have moaned that Channel 4 shows light entertainment, or too many property programmes, or too many imported sitcoms. But you literally cannot do that: Channel 4 must be assessed in the round, treated as a whole. Channel 4 and More4 and E4 and everything else.

"Everything else" includes the Film4 movies – we're a game show column, we'll talk about non-game television, but have no expertise in movies. People who do know about movies say that Film4 does a lot of good work, they're responsible for many great films.

"A culturally diverse society" is also important. Channel 4's biggest success in recent years has been to rehabilitate the Paralympic games. It's a long-term plan. In 2008, the BBC showed about 15 hours of edited highlights across the event. For 2012 – when the games were taking place in and around London – Channel 4 bought the rights. The corporation wanted "to champion unheard voices, to innovate and take bold creative risks, to inspire change and to celebrate diversity". Not only to show the games, but to change attitudes to disabled sport – and generally change attitudes to disability.

Channel 4 worked hard. In 2010, only one person in seven was looking forward to the Paralympics. When it came around, five people in seven watched the sport. Most viewers were more positive to people with disabilities, and believed society was also more welcoming. Without a penny of taxpayer money, without a single committee meeting in Whitehall. Channel 4 just went out and did something. Channel 4 built a stronger society.

From that success, Channel 4 has The Last Leg, a wildly successful chat show for young and diverse audiences. Channel 4's Friday also has Gogglebox, reflecting the tastes and interests of people like you, watching telly about people watching telly.

Channel 4's other commissions and acquisitions are similarly distinctive. In our sphere, Five Guys a Week and Murder Island were admirable programmes, even if they weren't the ratings successes they might have hoped to be. The Circle asked valuable questions about modern technology and mediated communication – can you trust anyone on the interwebs? The Great Cookbook Challenge told us a lot about the publishing industry. That we came away thinking so much less of the publishing industry in general, and the industry figures on the show in particular, is an unpredicted result.

All of these shows reflected Channel 4's core mission: appeal to the tastes and interests of a culturally diverse society. Often, that means challenging the status quo. If the status quo is fit for purpose, it will stand up to scrutiny and critique. If the status quo isn't up to the job, then examination will help to improve it. Those holding power will welcome challenge, if they are truly interested in making a better society.

We don't agree with the prevailing opinion that broadcast television will be dead in ten years. People said that television would end radio; this did not happen. People said that recorded music would destroy all musical ability; this did not happen. People said the smartphone was never going to catch on; this did not happen. People said that television would end movies; this did not happen. People said that the wireless telegraph would open communication and end war; this, sadly, did not happen.

Channel 4 has its place. It's a trusted voice on television, the channels air some of the most familiar and loved shows on television. Hollyoaks, now over a quarter of a century old, and still relevant. A New Life in the Sun honestly reflects the culture's desire to move abroad and improve your life, as though it's impossible to improve your life without moving abroad. Derry Girls, telling a rare story of young women from Northern Ireland. Countdown, as familiar and cosy as your best slippers. Only the most foolish people would dare take Countdown off your telly.

Some have argued that Channel 4 needs to compete with Netflix and Amazon. This is nonsense, this is a fusty old geography teacher digging out the loom bands, swirling a fidget spinner, putting on a Global Hypercolor t-shirt and expecting to look cool. It was "the internet" ten years ago, it was "digital tv" twenty years ago, it was "cable" and "satellite" and "colour teevee" in the decades before.

Just this month, we've seen Netflix's model collapse. It turns out that "make two series, encourage subscriptions, then leave people disappointed and regretting every cent they've ever spent" does not turn a profit. Channel 4 will find its own path through the future. Channel 4 is not run by idiots.

Fashions change. Quality is permanent, and so is its absence.

In other news

Earlier this year, the online game Wordle became a big hit. It's the one where you try to guess words, and get clues from earlier answers. When's the television version coming? It's already here, Lingo on ITV.

More recently, the online game Heardle has become a big hit. It's the one where you try to guess songs, and hear more as the game progresses. When's the television version coming? It's already here, The Hit List on BBC1.

Coming soon, the online game Figurdle, the one where you try to guess a number knowing only whether it's higher or lower than your last answer. Yep, there's a television version already, that's Numberwang.

The Americanofestivalen Song Festival Contest has been a massive success. Each weekly episode is seen by 1.5 million viewers across Europe and 1 million in the Americas. Buoyed by this result, the EBU has licensed the format to go north of the 49th. Eurovision Canada, or "Eurovision Canada" for viewers in English, will feature singers from all the provinces and territories. They hope to follow in the potato fields of Lara Fabian, Katerine Duska, Ester Peony, Natasha St-Pier, et Céline Dion. Does anyone know if any Canadian blokes can sing?

We're not publishing next week, but you might want to look at 100 BBC tv Gamechangers, a list to celebrate the BBC's television achievements since 1922. Our shows on the list include the Eurovision Song Contest, Blue Peter, The Generation Game, Mastermind, Strictly Come Dancing, and Bake Off.

This coming week is quiet. Finals week on Masterchef (BBC1, Tue, Wed, Thu) and The Drop (BBC3, Mon). Next Saturday has the BBC Young Dancer final (BBC2), while Sam and Mark play Catchpoint (BBC1).

There's an unexpected return for The Games (VM1 and ITV, nightly from 9 May), celebrities take on sporting challenges across the week. An expected return for the Eurovision Song Contest (RTÉ2 and BBC3, 10 and 12 May), and a new series of Glow Up (BBC3, 11 May). BBC2 takes a break from its usual fare and finds the Top Takeaways (nightly from 9 May).

We'll be back on Saturday 14 May, with the usual coverage of the Song Contest semi-finals.

Pictures: Magnum Media in association with Silver Star, Endemol UK Productions Midlands, Tuesday's Child East, Channel 4, Open Mike Productions, Shine (part of EndemolShine Group), Yorkshire TV, EBU/KAN.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.