Weaver's Week 2015-07-12

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

So far this year, we've done nothing but review new things. Mostly new shows, a few editions of favourite programmes, a book. But mostly new shows.

This week, we're catching breath, stepping back, and looking at some bigger questions. We've been watching Big Brother and Love Island for next week's reviews, and found our mind wandering. We might go over the heads of some readers, and we apologise if we lose you.

Cult television, fandoms, and other matters

It all began with a comment on Bother's Bar a month back.

Ben says:

- "I was having a conversation with a few members of my family, who are casual game show viewers, earlier this week and between us we made a few points which people here might have better-informed opinions on. See what you think:

- "We were talking about how much TV has changed in the last couple of decades, in particular viewing figures for shows and reflected that there aren't any 'cult' shows out there like The Crystal Maze and Blockbusters (for example) were in their day – by which I mean shows that are hugely popular among a certain demographic (in this case students). The best I could suggest was Only Connect, probably the same people a decade or so further down the line."

Countdown is a cult show. We'll explain why.

Countdown is a cult show. We'll explain why.

At this point, it would be helpful to provide a definition of "cult television".

Unfortunately, we can't. There isn't a standard definition of "cult television", it's a very nebulous concept. Media students know it when they see it, but they can't put their finger on what it is, still less why.

Some have suggested that "cult television" is "edgy or offbeat, appeals to nostalgia, or is emblematic of a particular subculture." That spectacularly unhelpful definition came from Cardiff University in 2004, in the introduction to a book on sci-fi and fantasy on telly. Plenty on Xena and Buffy and St*r Tr*k, nothing on the shows we call game.

TV Tropes dodges the issue, saying "a Cult Classic is a film or other work which has a small but devoted fanbase. Such fans are often proud of their membership of the cult and may resent it when the object of their devotion becomes a mainstream hit." So size matters, and something too big (at least when it starts) is unlikely to be a cult.

That Other Wiki blithers on about "Cult is an American television series created by Rockne S. O'Bannon that ran on CW in 2013", a contribution so utterly useless we come to appreciate the thought present in Cardiff's effort.

Ben's definition is a very good starting point: popular amongst a certain age group. We can't finish there, it lets us say that The Wiggles is cult television, because it's extremely popular amongst a demographic of children aged about four.

We think Blankety Blank was too popular to be a cult show, though it's close.

We think Blankety Blank was too popular to be a cult show, though it's close.

The Cult TV website proposes shows that are "set apart from the mainstream" and "objects of special devotion". Shows "often succeed only after a troubled start" and many viewers will be sure to watch the show and talk about it.

According to this definition, the key indicator point is that lots of people engage with the programme beyond the screen. There are fan clubs, discussion boards, people play along, attempts to re-enact the show, fan fiction; and these are relatively visible in the world at large.

We're going to run with this as a loose definition. Lots of devoted fans, and they're visible. Cultural impact beyond the original programme helps, but is not necessary. Starting small and growing big is OK, but starting big is not. There's also something slightly exclusionary about a cult show: it has in-jokes, points of reference known to the fans, and there's a bit of a learning curve to get the most out of the programme.

So we're going to ask a few questions. Has it grown organically? Is there a backstory for the initiated, and an opening for the newcomer? Does it inspire effort away from the studio? And is there plenty of fan-generated material?

Let's run a few tests. Does The Crystal Maze count as a cult show? Very much so. Permanent repeat on Challenge, the cyberdrome attractions, and the new crowdfunded attraction we're promised, and some very bad fanfic involving Mumsey and Ralph that we're sure we took offline last century.

Blockbusters? Perhaps, maybe. It's remembered with much fondness, but more for small moments and catchphrases ("Can I have a P please"). The show's ubiquity makes it emblematic of the 1980s, but that nostalgia lasts for only a few minutes. Seeing an episode reminds us that much of it was dry quizzing, enlivened only by the occasional entertaining contestants. Being a fixture on the schedules helps.

What of newer programmes? Pointless seems to fit our draft definition like a glove: from an obscure beginning on BBC2 to the heartland of BBC1's Saturday night schedule. Pointless has its amusing internal references – the definition of "country", and Xander's limited vocabulary to talk about the contestants. Given a copy of the board game, it's entirely possible to run a Pointless event in a pub. Fanfiction, yes, of a sort that would not be suitable for a Sunday morning. Pointless shows many of the signs of cult telly — apart from the bit where they shut newcomers out from the game. Excluding people seems to be alien to Richard and Xander, they're as welcoming as the day is long.

On the other side, and The Chase. Here, they've built up pantomime characters: Mark Labbett as an international larger-than-life character, Paul Sinha as the comedy foil, Anne Hegerty as the wicked stepmother, Shaun Wallace as the bloke from the office, and Bradley Walsh as someone forever on the verge of corpsing. This is fine television, and a lot of people love it. But it's difficult to recreate outside the studio, you'd need a quiz genius of your own. And we don't find that the show has grown so much as it's very slightly evolved. The fact there's a foreign version shown in the UK adds cult kudos, but we've not found any fanfic at all. No show is not a cult, but we find it harder to say The Chase is.

Deal or No Deal is certainly something you can recreate away from the studio, it grew through its own merits, and there's plenty of backstory. But Noel has gone too far, the show is almost all self-reference and precious little game. The fans who love the show make it difficult for the newbie to catch up, with their talk of "Wakeyist tendencies" and "Outright banker spankings". Maybe this is an extreme example of cult television, something so impenetrable to the outsider that it becomes like a religious experience – led by a charismatic preacher in a very bad shirt. The one piece of fan fiction we find is a crossover with Who Wants to be a Millionaire, a show too big to be cult.

We agree that Only Connect is amongst the most cultish of current game shows. Designed to be difficult, with a screechy soundtrack and Greek letters (later replaced by the even more esoteric Egyptian hieroglyphs), it requires effort to appreciate the programme. The learning curve is hard, and there weren't that many hand-ups when it moved to BBC2 last year. Only Connect certainly attracts rabid fans, the sort who will write at length about their favourite questions and say "ooh, it went downhill after the David versus Katie battle". There are fan walls, they encouraged fan walls, but only the very brave (or terminally foolish) would attempt to re-mount Only Connect in a pub.

Another contender for cult status: The Great British Bake Off. It's grown each year – from small to big to huge to the biggest entertainment programme on the telly. It's easy to get into the new series, but there are references for experienced viewers. Why do the hosts always gabble "On your marks, get set, bake"? What's with the Victoria sponge? Of course there is fan fiction, much of it involves icing served in unhygenic ways.

But fan fiction is not the only possible response to The Great British Bake Off. It's a baking show. People can imitate what they've seen on screen. They can bake!

Cult television, like other fannish activities, helps to service some deep psychological needs. Fans are able to interact with people who share your interests. They can work to achieve social capital – recognition, praise, being seen as "cool" by your peers. Winning a cake competition, entering a cake competition, feeding your friends cake that doesn't choke them. Fans can getting to know each other, sometimes closely, sometimes serving icing in unhygenic ways. Above all, the interaction from cult shows gives people permission to assert your identity through association with a group or activity.

To keep the ball rolling, there needs to be a regular influx of new fans. Newcomers need to see that they can get social status. They need to see that they can be creative, and be encouraged. They need to see that they might make friends, and maybe more. In short, the show needs to be as creative and responsive and unpredictable as Blue Peter.

Was Gamesmaster a cult show, or an example of a greater phenomenon?

Was Gamesmaster a cult show, or an example of a greater phenomenon?

There are a lot of other activities available these days, many of them were not present in the 1980s. Computer games have advanced over the past decades, and the equipment to play them has become more available. It's led to fewer people watching television. Some of the people who might have spent time on cult television have been distracted by cult video games. Others got caught up by Harry Potter, or anime, or online encyclopaediae of variable reliability. There are many opportunities to be creative, not all of them revolve around television.

Much later, Ben asks, "Do you think it is true that the biggest key to a successful format is simplicity?" For fannish activity (a necessary precursor to cult status), there is a tension. Too simple (Total Wipeout) and there's nothing for the audience to discuss. "Louise didn't get past the sucker punch. Meh." Too complex (Big Brother) and the audience has to spend all its time working out what is happening and has no capacity to build. Too few viewers (Reflex) and there's no audience to form a community.

All of these shows miss one of the key drivers. Simple shows don't let the viewers create, they only let the viewer consume. Complex shows don't allow the community to create its own magic, the producers force their reality on fans and squash creativity. And fannish activity requires fans, which requires viewers.

So, no, a very simple format is not going to ensure success, and might actually harm in the long run. There has to be enough to engage the viewer, and keep them coming back for more.

Ewan Spence, the Eurovision analyst, often quotes the recursive 1%. Of the 200 million people watching the performances, 1% might be motivated to vote. Of those two million, 1% might be motivated to download a track or find a CD. Those 20,000 are liable to become super fans, people who will see the performer play live two years later. If there are enough of them, there will be a reproducing fan community – we saw it some years ago with Justin Bieber on Twitter, we see it now with Loïc Nottet on Tumblr. But there has to be something to engage the viewers in the first place.

Ben also asks, "Is it likely that there will ever be a 'must see' game show now?" Likely, yes. Certain, no; the Week cannot foretell the future. Everything has to be just right; the show needs to be pitched at the right level, it's got to attract young viewers without appearing childish, it's got to inspire the viewer to do something. And it's got to have luck on its side; The Crystal Maze as we know it only happened because renovation of Fort Boyard took longer than planned.

What is important is that the genre continues to evolve. If it becomes stale and staid, or if it becomes too self-referential, it will ossify and die. The fate of Deal or No Deal should be a lesson: don't alienate the casual viewer, because some of them will become your biggest fans. See also the slow death of written science-fiction, and its rebirth as "young adult dystopia". And see the death and rebirth of Dr Who.

Throw things at the wall. Some of them will stick and become Pointless-sized hits. Some of them will fail through bad luck (5 Minutes to a Fortune) and be remembered with affection. Some of them will fade away (Beat the Nation) but contain the seeds of a greater hit. Some of them are Pointless, some are pointless. We don't know. Except for one thing: if you stand still, rely on old favourites, you're doomed.

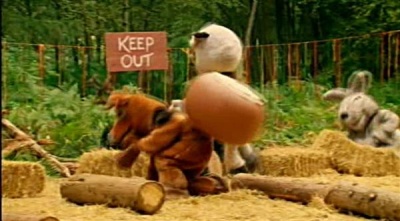

A tip for cult status from this year? Wild Things.

A tip for cult status from this year? Wild Things.

This Week and Next

A round on Who Dares Wins asked viewers to name television shows seen by 5 million people during 2014. Eighteen game shows are included on the list; see the Week of 4 January for the gory details. The FA Cup final (we assume they meant the men's edition) averaged 4.42m on ITV, because they included two hours of tedious preamble before the bully-off.

What of current entries? BARB ratings in the week to 28 June.

- The Eastenders remains Britain's most-viewed show, 7.3m saw it. Celebrity Masterchef the top game show, on 4.45m.

- Who Dares Wins attracted 3.55m, The Cube 2.5m, and The Chase (2.2m) beat Catchphrase (2.15m). We now know who wins a battle between Paul Sinha and Mr. Chips.

- Mock the Week (1.52m) squeezed ahead of Catsdown (1.51m) and Big Brother (1.45m).

- A League of Their Own gets 680,000 on The Satellite Channel, and Love Island brought 565,000 to ITV2.

- Viewing for children included Horrible Histories Gory Games (170,000 on CBBC), First Class Chefs (68,000 on Disney), and Big Brother (a round 1000 on MTV+1).

Lots of new shows this week. King of the Nerds (Sky One, Sun) is the Sunday service, Dragons' Den (BBC2) a prayer to mammon. The Link (BBC1), Fifteen-to-One (C4), and Two Tribes (BBC2) bring something to daytimes. University Challenge and Only Connect (BBC2, Mon) get the brain juices flowing, in time for Hive Minds (BBC4, Tue). More good news for intelligent television: Celebrity Love Island (ITV2, Wed) and Big Brother (C5, Thu) come to an end. There's also a new run of I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue (Radio 4, Mon) and we can miss America's Got Talent (Tru TV, Wed).

Photo credits: Yorkshire, BBC, Central, Initial West (an Endemol company), Love Productions, Hewland International, Mad Monk / IWC.

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Yahoo! Group.