Weaver's Week 2025-04-20

Last week | Weaver's Week Index | Next week

This week, we look at a show that has literally had us shouting at the telly. Cries of "Go on! Go on! Yes!" are interspersed with "What are you doing?!" and "Fer @#!%#'s sake, Johny Enmedol, that's no way to make a telly show!!!" We have a lot to say about

Contents |

99 to Beat

Initial (part of Banijay) for ITV, from 22 March

You probably read The Hunger Games a few years ago, or saw the films. It's the tale of young people who are thrown into an unfamiliar environment, given strange and unusual tasks, with the worst performers killed in quite a callous manner. Published in 2008, The Hunger Games was a response to the constructed reality game shows of the early aughts, crossed with television coverage of wars. Beyond Katniss and Peeta and the others, the main players in The Hunger Games are the Gamesmakers, television producers who shape the story to keep the audience interested. The Hunger Games also has elements of classical myths like Theseus and the Minotaur, but we're mostly a tv column and The Hunger Games is – canonically – a made-for-television spectacle.

The Hunger Games inspired a lot of derivative works: a whole genre of post-apocalyptic books came out over the next few years, all trying to be "the next Hunger Games". None succeeded: Divergent came close, The Maze Runner ran out of ideas after the first book, and our librarian friend insisted there was unfulfilled promise in Tanith Lee's Claidi Journals. There's a clear line to the recent Squid Game, a Korean-language drama where the games are simple and the stakes are high.

And so the idea got chewed up, recycled, spun around and reused throughout pop culture. Eventually, the antidote to reality tv came back — as reality tv. Homo Universalis premiered on Belgian telly in early 2018. A hundred normal people are brought into a sports hall, and given simple tasks to do. The worst at each task is removed from the game (by being sent home, they don't go in for executions on pre-watershed Eén). Last player standing wins holidays for a year. And if that sounds like one segment in a magazine show, that's exactly how they aired it – one mini-episode each weeknight for weeks.

The show achieved great success in the Netherlands as De Alleskunner, where episodes last an hour and stitch together lots of tasks. It's since been made for German viewers, those in Poland, Norway, Sweden, Italy, and now comes to these shores.

We gave 100 people...

They stand in a large circle, each illuminated by a spotlight. A couple of nets contain something colourful in the roof – perhaps that'll be one of the tasks in the studio.

Turns out that it is one of the tasks. The things in the roof are exercise balls, those bouncy springy things that some people love to sit on. The competitors are going to be asked to find an exercise ball, and sit on it. Simple.

Two problems. One: the contestants will be blindfolded, they literally cannot see where they're going. And another problem, there are 100 contestants, but only 99 exercise balls. Someone is going to be left out, someone is going to be the last person standing. And that person is going to be eliminated from the contest at once.

Quite simply, that is what they do on 99 to Beat. Simple challenges, and the aim is not to be the absolute worst at any of them.

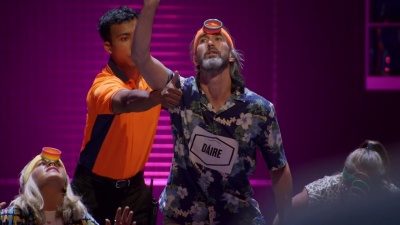

A marshall gives the thumbs-up of success to Daire; all contestants have their name pinned on their shirt. (Initial)

A marshall gives the thumbs-up of success to Daire; all contestants have their name pinned on their shirt. (Initial)

It quickly becomes clear that the challenges are relatively low-tech. In the first episode, our contenders are asked to curl up a slinkie on their forehead, balance a part-filled can on its edge, hold a ping-pong ball on a spoon in your mouth, defrost a t-shirt and put it on. These are reasonably accessible items: we can imagine school teachers drawing many ideas from this programme. (Get your Year 7 class to hold spoons in their mouth? That means they can't talk!)

Hosts of 99 to Beat are Adam and Ryan Thomas. They've been on Coronation Street and Emmerdale Farm, they've been on I'm a Celebrity and Dancing on Ice. After four episodes, we're still not convinced by the brothers' work. They are enthusiastic, they are engaged, they are literally present in the darkened warehouse as the events take place. All of these are positive attributes.

But they've not yet told us something we cannot see for ourselves. The role of the commentator is to add something to the show, give the viewer some information that is not obvious. "Ooh, look at Brian whacking the chair with his t-shirt!" as we look at Brian whacking the chair with his t-shirt. If we wanted a simple view of what's happening on screen, we'd ask for Audio Description of the programme. (99 to Beat is not Audio Described. ITV's other Saturday night quiz The 1% Club is, and we encourage you to watch one episode with Audio Description on.)

What other possible roles could the commentator take? The commentary could be a neutral and factual description of the events, like Marcus Bentley on Big Brother. "Just four contestants haven't curled up their slinky: Julian, Dick, Anne, and George K." There's already a voice to explain each challenge, and plenty of natural sound from the competitors. And, because 99 to Beat is a show filmed in the twenty-first century, there are a lot of cutaways to the contestants explaining what's going on. We wonder if neutral voiceover plus lots of contestant talk would make for a more fulfilling show? Guess we'll never know.

Alternatively, 99 to Beat could have followed Total Wipeout and Takeshi's Castle, and given a blatantly silly commentary on what are blatantly silly tasks. However, this would have changed the show's tone, made it frivolous, and stopped us from getting involved with the contestants. We're glad they didn't do a frivolous commentary, it would have risked the same trap as The Crystal Maze a few years back. After four episodes we reckon the Thomas brothers are hitting roughly the right tone – but if there is a second series, they do need to bring something beyond what we see.

A silly commentary would mislead the viewer – we reckon 99 to Beat is a serious commitment. Contestants give up two weeks of their lives for this show, and exactly one of them will get a prize. (The prize is £25,000 (€ 30.000), slightly more than one year's wage in a minimum wage job.) The Gamesmakers had to invest in 99 exercise balls, 98 slinkies, 100 t-shirts with players' names on (and one large freezer). It might look simple, but the logistics behind this show are frightening.

At each elimination, there's a sarcastic send-off from The Voice, a disembodied announcer played by Carla Terry. We found the tone of these announcements to be massively at odds with the warm and genuine applause from the remaining players, and the Gamesmakers seemed to tone down the sarcasm as the series wore on. Good; the right tone is the delivery of a dad pun, something that knows it's a limp joke.

...but not everything is rosy

99 to Beat has a clear aesthetic. Dark background, harsh spotlights, vari-lights swooping at the start of every challenge so we literally cannot see the beginning. Because there are so many contestants, it's not possible to use technology like on The Cube and Gladiators – we don't swoop round the arena showing action from all angles. Nor do we get many replays – only to help determine close results, not of general action.

Too many challenges on the first episode made for bad television. The exercise ball challenge was always likely to finish with the last few seats in the middle of the group, quite hard to find. And we didn't get to see the last players sit down, which was entirely disappointing. For whatever reason, the producers only used hand-held cameras, they didn't rig up fixed cameras around the edge of the arena that they could use to get shots almost everywhere. (We're thinking of the little rotating cameras that they have on the Big Brother set, perhaps mounted at some height and trained to zoom at various points in the arena.)

A little later on, the balance a can on its side challenge also ended without a shot of the final person succeeding, which actually felt less excusable because we had known for a few minutes who the last players were and they were sat at fixed desks. The opening ep's last challenge, to get a coin out of a piggy bank using a paper clip, was also poor television as we didn't see the coins come out.

For the Gamesmakers not to have footage of one finish is unfortunate, but forgiveable. For them to lose three out of the opening seven is very poor. Again, this wasn't such a problem in later episodes – the Gamesmakers were learning as they filmed the show.

The Hunger Games author Suzanne Collins discussed how her book is modelled on television shows:

- Well, they’re often set up as games and, like sporting events, there’s an interest in seeing who wins. The contestants are usually unknown, which makes them relatable. Sometimes they have very talented people performing. Then there’s the voyeuristic thrill—watching people being humiliated, or brought to tears, or suffering physically—which I find very disturbing. There’s also the potential for desensitizing the audience, so that when they see real tragedy playing out on, say, the news, it doesn’t have the impact it should.

Back on 99 to Beat, a passage in the third episode was very difficult to watch. We can reasonably expect that tasks will be fiddly and frustrating, and that contestants will show that frustration. We might not be so forgiving when the same contestant is eliminated just after by sheer chance. And we're certainly don't expect them to be followed outside by a camera, or that details of their vent would be shown on network television. ITV and its contractors Initial have a duty of care to contestants. In this column's view, the production did not do their absolute best for the contestant and we are not convinced they met that duty of care.

The show is fast, there's a very brisk cycle of explain – setup – start – game's happening – tense bit as we approach the end – perhaps some pieces to camera from those involved – loser identified – bad pun applause and leave. If we're lucky, we might get a short piece with some of the contestants talking off-stage – either in the warehouse or the concrete just outside – and then it's on to the next challenge.

Because the format tends to concentrate on people who are at risk of elimination, those who struggle with a particular type of challenge will become familiar faces. The off-stage talks let us meet other contestants, ones who will be useful to get to know during the series. Have they introduced the overall winner in this way already? It's very possible – remember, the Gamesmakers can edit with foreknowledge of the result, they can guide us and lead our emotions.

Perhaps we're too accustomed to The Traitors, where the cast is large but the eliminations much slower, and we get to know something about everyone in the first few editions. We're writing before this weekend's episode, so there are 34 players still in. There must be at least a dozen we've not spoken to or heard mentioned, and that is not good: these people have completed everything thrown at them, yet they have not risen above the level of background character. Does that mean they're destined for elimination next time? Or will the winner emerge out of nowhere – gosh, hope not.

But how have they cut from 100 contestants to 34 in just four episodes? That's 66 eliminations in four ITV hours, how can they possibly have had 66 different challenges?

The team games

They haven't had 66 different challenges. Once in each episode, contestants are randomly assigned into teams. They're given a task to complete, and whichever team comes last in the challenge is eliminated. All of them. Twelve people eliminated in one fell swoop.

Let's first look at how this affects 99 to Beat as a television programme. To make us care about the group elimination, we've got to have stakes in the groups. At the very least, we need to know some of the players who are going to be in the bottom groups. The betrothed couple who find themselves on opposite teams, the twins who come to the realisation that one must be eliminated. The characters we've seen before, familiar faces who aren't just names in the crowd.

To set up these stakes, the Gamesmakers have to spend a lot of time and effort – there's only so much they can do to build up to the big elimination in the early episodes. And when it happens – whoomph. That's a lot of people gone. A lot of airtime wasted on people who go together.

And if the Gamesmakers have done their job properly, we will care for these people. We will be sorry to see them go, we will wish them well. We as viewers deserve to see the eliminated players have their moment of glory, or ignominy, or just to say a proper goodbye with bad pun and a moment in the middle. Group eliminations don't even give us viewers that closure. It's an incomplete farewell, it's not emotionally satisfying.

There are editorial reasons why they need to lose a lot of players quickly – ITV has only allocated eight hours to the show, and that doesn't give enough time to whittle down 100 people one by one. From a viewer's point, we can accept multiple eliminations under limited circumstances:

- We're fine if we don't have much emotional attachment – so episode 1 is fine, but even episode 2 felt like too many friends leaving at once. Remember how The Hunger Games has the bloodbath at the start of its tournament, and not halfway through?

- It could be possible to eliminate performers who don't meet minimum criteria – for example, in the game where you're firing a cork from a champagne bottle, failing to clear the start line would lead to an instant exit.

- And if it is necessary to have bulk eliminations, make sure we viewers get a fair chance to appreciate the contestants who have put in their effort. Maybe they don't get to speak to the camera, but we at least deserve to get to clearly see names and faces. If that means smaller groups, so be it.

Many of these people caught up in group eliminations are out through no fault of their own, just from being drawn into the wrong group. The cornerstone of 99 to Beat is that every elimination is "earned" through being last in a contest. We're far from convinced that drawing out the unfortunate colour is enough to earn elimination. If the players have some agency in picking their teams, that would make defeat feel less unearned.

And that got us thinking. Is there a way we can measure what skills are being tested on 99 to Beat? Can we come up with some classification of challenges under larger headings, then use that to measure eliminations? Yes, yes we can.

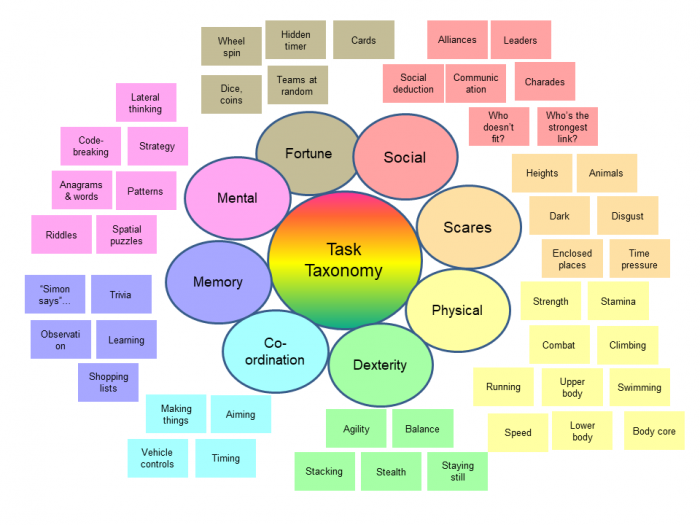

Building on the work of one of our friends on Tumblr – and giving credit where it's due – we present Twil's Task Taxonomy.

Eight segments:

- Social (communication, leadership, alliances, who is the mole)

- Scares (discomfort, fears, animals, the dark)

- Physical (strength, stamina, speed, moving your own body)

- Dexterity (balance, limb and hand control, agility)

- Co-ordination (aiming, very fine motor control, timing)

- Memory (observation, learning, recall over short or long term)

- Mental (logic, pattern recognition, riddles and codes)

- Fortune (luck, being in the right place at the right time)

Our working thesis is that the Gamesmakers on 99 to Beat will not significantly test Social or Scares, and eliminations will over-index in Fortune compared to everything else. We'll come back to this taxonomy in a couple of months, once the series has finished and after we've got through Eurovision and given The Genius Game its due.

For now, we can reach some conclusions about 99 to Beat. The first episode was rocky and ropey; since then, the show has found its tone and found its voice. The commentary is enthusiastic if a bit too obvious. The simple aesthetic and replicable challenges give the show lots of appeal, but our emotional engagement as a viewer is compromised by too many bulk eliminations. There shouldn't be so many players in the final 34 we don't know at all. It's a show of hot and ice-cold, massive plus and huge minus, heartwarmingly good bits and scream at the telly bad bits.

And we're engaged with 99 to Beat. Not just on the intellectual level, but on an emotional one. Whoever wins will have earned their prize; we can all pick out people we would like to win and barrack for them, and sigh with relief when they're safe, and be on the edge of our seat when they're in the final few. It's like watching a sportsball team, only for lower stakes.

Once again, the Gamesmakers at Initial prove able to tap into our emotions, and make a human connection out of the most unlikely material. And, for this column, that is the hallmark of a great show: we care about it. Well done to them.

We will look again at 99 to Beat over the summer.

In other news

Wink Martindale has died, aged 91. He was one of the legendary American game show hosts, Gambit and Tic-Tac-Dough. He later co-created Bumper Stumpers – where contestants make words out of car number plates – and hidden camera quiz Instant Recall. Wink began his career as a disk jockey in Memphis, and was one of the first people to interview local singer Elvis Presley. Our friends at Buzzerblog have a fuller obituary.

Colin Berry has died, aged 79. He was best known as a newsreader and relief presenter on Radio 2, and occasional guest on panel shows. He was known internationally, as the sane and sensible voice of the BBC's votes to the Eurovision Song Contest for over two decades.

Be gone ITV will "retire" its ITV Be channel during June. All of the reality guff – The Only Way is Essex, The Real Housewives of Timperley, um, whatever else they show – will move to ITV2. In place of ITV Be, the nation's former favourite button will launch "ITV Quiz", which will draw on ITV's "popular, market-leading quiz and game shows".

That is literally all ITV has told us, a throwaway line at the bottom of a press release. No, we have no confirmation of what the new channel will show, nor what the knock-on effects will be to the existing Challenge channel. We do note that there's already quite a lot of repeated game shows on ITV2, with Celebrity Catchphrase and Limitless Win and Epic Gameshow all filling off-peak hours, and Deal or No Deal counting to the sign language requirement. Expect lots of these shows to move to the new ITV Quiz channel. Will they be joined by The Chase (currently with Challenge) or Tipping Point (sold to UKTV's Watch channel)? We don't know, and will have to wait and see.

Rolling on Two more series of The Wheel, which has been renewed as part of a deal with Michael McIntyre. Although it's not as popular as it was when it launched, The Wheel remains fun and entertaining, with questions just the right side of interesting.

Rolling out Thought you'd heard the last of In for a Penny? Think again! Stephen Mulhen's new show, You Bet!, will film in a different location each week, presumably going around the country to meet its challenges. Prizes are trimmed – now "just" £5000 for charity, and we're not sure if they're going to keep the audience vote that none of the UKGS editors seems to like.

Yes. Yes, you are. Jimmy Carr is to host a Comedy Central panel show where comedians opine on the morals of members of the public. The show – which is listed in the press release as Am I the A**hole? – is based on a Reddit board where contributors judge each others' behaviour. Tuesday's Child made the show, which is set to air "later this spring".

Quizzy Mondays

Warwick booked their place in the University Challenge semi-final, beating UCL by 1-0, the question about Cassini felt like it lasted almost the entire show, wittering on about quadratic curves in a way that had this column making a shape in our Ovaltine. Warwick also scored on the architecture of Weil-am-Rhein campus, Roman years with many emperors, and flags containing Phygian caps. LSE were in the match until half time, scoring strongly on the poet Ted Hughes and the Cinecitta film studio, but Warwick's superior buzzer proved the difference. 220-125 the final score, both sides getting more than 60% of bonuses right, but UCL fall below 50% when we consider starters and bonuses.

Bristol took the final place, beating Queen's Belfast by 200-65. Very much a match decided on the buzzers, Daniel Rankin took five for QUB, Ted Warner six for Bristol, but Bristol also took half-a-dozen from their other players. Very much not Queen's night, and not the greatest half-hour of television. Bristol did what they had to do, and we presume they will next play Christ's Cambridge; Warwick against Darwin Cambridge seems logical.

John Harden made the Mastermind final, achieving a Perfect Round on the Rumpole stories of John Mortimer, and then a round dozen in his general knowledge set. Cathryn Gahan was also Perfect on the films of Mel Brooks, and the couple of errors near the end mustn't take the shine off a superb performance. The other semi-finalists were Arnav Umranikar (Homer's Odyssey) and Roopam Carroll (the rapper LL Cool J).

Dom Tait also made the Mastermind final, squeezing an extra question moments before the end of his round on wild cats, and then blitzing the general knowledge round with a rapid-fire 15 (FIFTEEN) points. It may have put the frighteners under Dan Shoesmith, who had equalled Dom's score on West Ham FC, but quickly found general knowledge not to his liking. A good effort from James Waller (battle of Gettysburg) and an honourable fourth place to Aine McMenamim (tragedies of Euripides).

Last night, we had new editions of Blankety Blank (BBC1) and Sally Lindsay's 70s Quiz Night (Channel 5), both on the relevant catchup service.

From China to India: it's the new series for Race Across the World (BBC1, Wed). Hello, households! Scotland's Home of the Year returns (BBC1 Scotland, Mon) The grand final for Celebrity Big Brother (VM1 and ITV, Fri). Sportsball on BBC1 next Saturday might move Blankety Blank and Pointless Celebrities; it won't shift the Got Talent semi-final (VM1 and ITV, Sat). And what did Harry from The Traitors do next? (BBC2, Sun)

To have Weaver's Week emailed to you on publication day, receive our exclusive TV roundup of the game shows in the week ahead, and chat to other ukgameshows.com readers, sign up to our Google Group.