Mastermind

(→Celebrity Mastermind) |

(→Theme music) |

||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

The theme tune is called ''Approaching Menace'' by Neil Richardson (who, incidentally, co-composed and conducted the score for the film ''Four Weddings and a Funeral''). | The theme tune is called ''Approaching Menace'' by Neil Richardson (who, incidentally, co-composed and conducted the score for the film ''Four Weddings and a Funeral''). | ||

| - | The 2010 final featured a new orchestration recorded by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. | + | The 2010 final featured a new orchestration recorded by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. BBC Manchester then promptly forgot they'd ever commissioned it and reverted to the original library-music version for the 2010-11 series, before bringing it out to serve as the main theme for the 2011-12 run. |

== Trivia == | == Trivia == | ||

Revision as of 13:03, 6 November 2011

Contents |

Host

Alan Watson (unaired pilot)

Peter Snow (radio version)

Clive Anderson (Discovery series)

Betsan Powys (Mastermind Cymru and Mastermind Plant Cymru)

Des Lynam (Sport Mastermind)

Griff Rhys Jones (2011 special)

Co-hosts

Scorer and Timekeeper: Mary Craig (often referred to as the "Dark Lady" who sat by Magnus' side but never spoke).

Broadcast

BBC 1, 11 September 1972 to 1 September 1997

BBC Radio 4, 1998-2000

Discovery Mastermind: BBC Manchester for Discovery Channel, 14 November 2001 to 16 January 2002

BBC 2, 30 December 2002 (one-off celebrity special featuring Adam Hart-Davis, Janet Street-Porter, Vic Reeves and Jonathan Meades)

BBC 1 (Junior and Celebrity versions) and BBC 2, 7 July 2003 to present

Mastermind Cymru: BBC for S4C, regular series 8 October 2006 to 8 December 2007, plus celebrity specials to 26 December 2009

Sport Mastermind: BBC 2, 8 July to 20 August 2008

Mastermind Plant Cymru: BBC for S4C, 8 December 2008 to 15 October 2009

bbc.co.uk webcast, 5 to 6 March 2011 (24 Hour Panel People)

Synopsis

Considered by many to be "the ultimate test of memory and knowledge", Mastermind is a simple quiz. However, at times it can prove quite fascinating.

Originally set in the chapel of a college or hall, nowadays a studio in sunny Manchester, John (originally Magnus) puts four contestants through their paces. Each contestant has previously submitted a specialist subject, which can be anything you like as long as the subject is deep enough. These are judiciously researched beforehand.

The seating arrangements

The black chair that has become the programme's trademark.

The black chair that has become the programme's trademark.In Round One, each contestant goes up to the famous black chair (pictured) one by one, and is asked "Name?", "Occupation?" and "Specialised subject?" The contestant is then subjected to two minutes of quick-fire questions about their subject. (Contestants can pass if they wish, although in the event of a tie these are taken into account.) At the end of the two minutes, a buzzer is sounded and, if John is in the middle of a question, he uses one of television's most famous catchphrases, originally used by Magnus: "I've started so I'll finish". (Though unlike Magnus, he does not follow this up with "And you may answer".)

And now, general knowledge

After each of the four contestants have had their go, the scores are read out in reverse order. Round Two is played similarly to Round One, but this time the subject is always general knowledge, and contestants play in the order of position, the person with the least points going first.

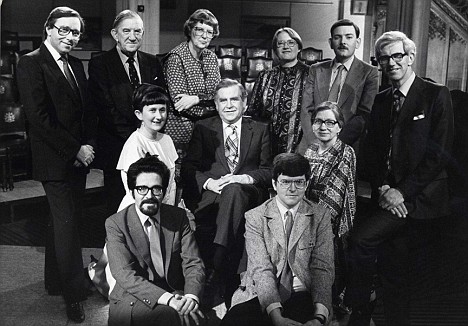

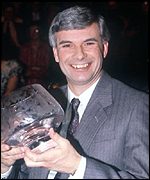

Halfway through the 1990 final. The contenders are, left to right: Brian Bibby, Helen Grayson, the champion-to-be, David Edwards, Paul Webbewood and Chantal Thompson

Halfway through the 1990 final. The contenders are, left to right: Brian Bibby, Helen Grayson, the champion-to-be, David Edwards, Paul Webbewood and Chantal ThompsonAfter that, the scores are read out again and the winner declared. (If there is a tie on points, the player with the "fewer or fewest" passes is declared the winner; if there is still a tie after passes are taken into consideration - a very rare occurence - then there is a "sudden death" tiebreaker in which both players separately face the same five questions and whoever gets the most right, wins.) The winner goes through to the semi-finals, the four (later six) winners of them going through to the final for the chance to win the engraved punchbowl which signifies the title of Mastermind champion.

And that's it. Bells? Whistles? Not one (with the possible exception of the intriguing black chair). And it doesn't need it for Mastermind, despite being simple, has become something of a national institution.

The end... not quite

The very last programme (at least, that's what it seemed at the time) was in 1997, where the programme went for the ego-trip of a lifetime to the remote Scottish island of Orkney to film in St. Magnus (geddit?), an 860 year old cathedral. Anne Ashurst, a novelist for Mills and Boon, was crowned the 'last ever' champion, and Magnus Magnusson got to keep the black chair, as was only right.

St. Magnus Cathedral

St. Magnus CathedralBut it wasn't quite the end. Peter Snow hosted a version on BBC Radio 4 (although the impact of the chair was a bit less...) and what felt like a slightly dumbed-down version ran for a year on the Discovery Channel, with a redeeming feature being a separate final for interactive play-along viewers.

And that really did seem to be it until a celebrity special aired in 2002...followed by the show itself returning the next year! Everything remained pretty much the same, including the theme tune and chair (a replica of the original) though there was a bit more interaction between new host John Humphrys and contestant. (At least, there was until the 2009-10 series, whereby Humphrys no longer chatted to the contenders in between the rounds: instead, the contenders all did a brief spiel just before their first rounds about why they'd chosen their subjects and what they found interesting about them. However, that's now also gone in the 2010-11 series, because the general knowledge rounds are now two and a half minutes long). Some believe the show has been 'dumbed down' seeing as more people are choosing subjects such as Doctor Who rather than The Crimean War, but it's good to see the show back again on the BBC.

There's even been a regular kids' series, a Welsh-language version for S4C, and (almost inevitably) a children's series in Welsh. In 2008, Des Lynam returned with a sport-themed version. It wasn't his first time in the question master's chair, as he used to host special editions of the quiz on FA Cup Final mornings, though he does seem uncharacteristically wooden in the role of questionmaster. It does however show what a good, no, let's make that great, format Mastermind is. As long as the basic structure is in place, it's almost impossible to mess it up, wooden host or not.

Who's the greatest?

As if being crowned Mastermind wasn't honour enough, winners have often been invited to take part in further contests against other quiz show champions. In the 1970s there was Supermind, and the 1990s gave us Masterbrain, in which winners of Mastermind and Brain of Britain played off against each other. 1997 even saw a University Challenge crossover, with that year's four "last ever" Mastermind finalists making up a team to take on UC's reigning champions (the latter won). The 1997 winner, Anne Ashurst, also appeared on 'University Challenge - The Professionals' as part of the Romantic Novelists team, who were the defeated finallists in the 2005 series.

In 1979 Magnus hosted a special Mastermind International programme involving quiz show winners from around the world (including UK Mastermind champions David Hunt and Rosemary James, together with the champions of the Nigerian, Australian and New Zealand versions of the show, and winners from Ireland's Top Score and the Canadian version of The $128,000 Quiz), which was won by the Irish contender John Mulcahy. Following this, Mastermind International became an annual event for the next four years. In 1980 it was hosted by Magnus again, but after that it followed a Eurovision-type "winning nation hosts next year" system. In 1981 the programme was filmed in the Sydney Opera House with questionmaster Huw Evans, who hosted the Australian version of the show. The 1982 edition was made in New Zealand and hosted by Peter Sinclair, who was the questionmaster on the local versions of both Mastermind and University Challenge. Finally, after the first British victory, 1983 saw Huw Evans fly to the UK to present what turned out to be the last edition, made at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford.

There was also a Mastemind Champions contest aired over three consecutive nights in 1982 (in lieu of a proper series that year) featuring the first ten series champions - five in each of two heats, top two from each progressing to the final. The winner was David Hunt, with the specialist subjects of the history of Crete, and Alexander the Great. 2010 saw a Champion of Champions competition featuring sixteen past winners, which the 2005 champion Pat Gibson won with specialist subjects of Pixar films and Great Mathematicians. In addition to Gibson, the Grand Final line-up comprised the 1993 champion Gavin Fuller, the 1990 winner David Edwards and the reigning champion Jesse Honey, who managed to set two new records in his first round (see Scoring records, below). The final scores were most impressive - Fuller and Edwards tied for third place on 32 points, while Gibson and Honey tied on 36 points, but Gibson won it on passes - and it should be noted that the general knowledge round was two and a half minutes long in this case. Humphrys reckoned that there had never been a contest quite like it before, and 2008 champion David Clark (who lost to Gibson on passes in the heats) suggests that it may be the highest four-person aggregate score ever (it's certainly the highest for the Humphrys era).

Key moments

The final of each series attracts a lot of attention, the most famous winner being Fred Housego, a London taxicab driver. Mr Housego was the first of three drivers to win the series, since Christopher Hughes, a London Underground train driver, won it in 1983 and Ian Meadows, a hospital driver, did so in 1985.

Catchphrases

"I've started so I'll finish." (At the end of his last-ever show, Magnus adapted it slightly: "I started, and now...I've finished. Bye bye".)

"Hello, and welcome to another round of 'Mastermind', with me, John Humphrys..."

"May I have our first contender, please?"

"And at the end of a close competition, let's glance at the scores."

"...And it doesn't get much closer than this..."

"So on now to the second round, the general knowledge round - and remember, if there is a tie at the end of this round, then the number of passes will be taken into consideration, and the contender with the fewer or fewest passes will be declared the winner. And if there is still a tie on passes, then there will be a sudden death play-off" (or "shoot-out", as John Humphrys has sometimes put it).

(Magnusson-era): "...and you may answer". Also: "Our thanks and commiserations to our three gallant runners-up!"

Magnus Magnusson normally signed off with, "All that it remains for me to do now is to thank the authorities here at (wherever) for all their great kindness and hospitality to us. Next week, we shall be at (wherever else). Until then, from 'Mastermind' in (wherever), it's goodbye!" John Humphrys signs off more simply, but equally effectively, with, "Do join us next time for more 'Mastermind'. Thank you for watching - goodbye!" In fact, nowadays he says "Join us next time for more Masterminds", which is really rather cute. He's not going to like us for saying that, is he?

(John Humphrys, since 2009): "Four contenders, two rounds of questions, one aim - to become the nation's Mastermind" and, for the 'Champion of Champions' series, "Four former winners, two rounds of questions, one aim - to become the 'Mastermind' Champion of Champions".

Inventor

The idea for the show comes from the experiences of the producer (Bill Wright) when he was a Prisoner of War during WWII. He was often asked for his "Name", "Rank" and "Number" (the only information he was obliged to give under the Geneva Convention). He decided to change this to "Name", "Occupation" and "Specialised Subject". Note the dark mise-en-scene, which is meant to give a sort of individualised, cross-examination feel. In the early days, this theme was even carried through to the on-screen credit for Magnus Magnusson, who was described not as "questionmaster" or something fluffy like that, but as "Interrogator".

Theme music

The theme tune is called Approaching Menace by Neil Richardson (who, incidentally, co-composed and conducted the score for the film Four Weddings and a Funeral).

The 2010 final featured a new orchestration recorded by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. BBC Manchester then promptly forgot they'd ever commissioned it and reverted to the original library-music version for the 2010-11 series, before bringing it out to serve as the main theme for the 2011-12 run.

Trivia

Contenders

One quirk of the show is that participants are always referred to as "contenders", never "contestants". Well, almost never, as both Magnusson and Humphrys have been known to slip up on occasion.

Because the first three Mastermind champions were women, the BBC were once apparently on the verge of debating whether to change the title of the programme to 'Mistressmind'. And if you believe that, you'll believe anything! Nevertheless, it's true that the 1975 series was accompanied by a lot of speculation in the press about whether a man would ever - or could ever! - win the title, which all proved somewhat academic at the end of that year's contest when a man, John Hart, did just that. The balance was largely redressed throughout the 80's, as the mix of male and female victories became fairly even, but it later became rather more male-dominated. A relative lack of female applicants has often been a concern for producers of quiz shows, as reflected in the fact that Magnus would often ask for more ladies on the show when requesting future contestants. Gordon Burns often did the same thing on The Krypton Factor, as did William G. Stewart on Fifteen-to-One. The problem is particularly bad for "prestige" shows like these since they can't really be seen to indulge in positive discrimination in the way that other, less "serious" shows can.

The oldest-ever 'Mastermind' champion, at 64, was Sir David Hunt in 1977, while the youngest-ever, at 24, was Gavin Fuller in 1993. It was therefore most appropriate that Hunt presented the trophy to Fuller in the latter year's Grand Final.

Probably the first-ever contender to win the game before he'd even started his second round was a 2005 semi-finallist, Tom King. He'd scored 17 on his specialist subject, namely "Dad's Army" and all his three opponents finished with scores below that. "Well, I can't pretend that it's a close match", declared Humphrys, "but we're going to test your general knowledge anyway", and King went on to score a total of 24. One contender to match this feat was the 2006 finallist Ray Eaton in one of his first two rounds.

Several series champions had been highest-scoring runners-up in at least one of their previous matches. They included Margaret Harris, David Edwards, Anne Ashurst and, from the 'Junior' series, Domhnall Ryan. This has also occasionally happened on University Challenge and quite often on The Krypton Factor.

Champions, especially those from non-academic backgrounds, sometimes find that their success leads to other TV and radio work. Cab driver Fred Housego, the 1980 champion, went on to present a BBC1 series entitled 'History On Your Doorstep' and he appeared on certain other shows too, before settling into a long career on local radio. 1983 winner Chris Hughes, then a train driver, went on to appear on other quizzes such as Call My Bluff, in which he helped Frank Muir to victory and The Adventure Game, in which he was unfortunately evaporated for giving an inappropriate gift to the Rangdo - but he's more than bounced back from that little setback, since he's now best-known as one of the Eggheads. He also narrated a series on steam trains (which had been one of his specialist subjects) for TVS, and most unusual of all, was the subject of a QED programme about what makes someone clever.

Other champs who turned up elsewhere included the 1984 champion, Margaret Harris, appeared on a special Christmas edition of Bullseye that same year and proved surprisingly adept at dart-throwing as well as answering questions, and the 1993 (and youngest-ever) champion, Gavin Fuller, who went on Noel's House Party, on which he was gunged (well, what else could you expect on that show?) and was later the defeated finallist on Grand Slam. Other than that, however, the majority of 'Mastermind' champions have returned to (relative) obscurity following their victories (but see also 'Who's The Greatest' above).

The famous Arfor Wyn Hughes, who scored only 12, revealed on 'Disastermind' (part of a 'TV Hell' night screened on BBC2 around 1992) that his appearance on the programme caused him considerable grief with the pupils that he taught. Apparently, whenever he asked one of them a question in class, the response would inevitably be, "Pass!" followed by a cheeky snigger - and, as if that wasn't bad enough, the kids would deliberately hum the 'Mastermind' theme tune as he walked down the corridors. Somehow, the famous "Scooby Doo" cartoon phrase "I would have gotten away with it if it hadn't been for them pesky kids!" springs to mind.

Another former contender to appear on 'Disastermind' was the 1974 finallist Susan Reynolds (now Halstead), who had apparently been partially concussed when hit in the face by a brass knob on the wardrobe door in her hotel room not long before the recording and found herself in the black chair facing, as the programme described it, 'two Magnusses'. As a result, she struggled considerably on her specialist subject, 'British Ornithology', scoring only 5 points: she made a comeback in her general knowledge round, but unfortunately it was too little, too late, although she did manage to finish in third place. She later stated in interviews that she was knocked out "by three other contestants and a brass knob". Magnus actually went to visit her to find out more as part of another quiz-related programme, some time after his version of the show had finished, because he had suspected at the time that something wasn't right and that she may well otherwise have won the series. He always remembered her fondly as the greatest champion that 'Mastermind' never had - and she would certainly have also been the youngest-ever champion, as she was only 19 at the time.

1990 champion David Edwards subsequently scooped the top prize on Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, while Millionaire winner Pat Gibson completed "the double" the other way around in 2005 (and made it a treble by going on to win Brain of Britain as well). Humphrys spoke to Gibson during the latter's first round about his winning WWTBAM and asked him, "What would you do if we were to give you a million pounds?" then added hastily, "No - I'm getting a voice in my earpiece, saying, 'Don't go down that route!'". (Yes, one can believe that it was best that he didn't). There was also a victory for 1995 champion Kevin Ashman at Torquay in the live, touring stage version of WWTBAM.

The 1994 champion George Davidson received his prize from none other than Bamber Gascoigne. It is surely no coincidence that this final went out just a month before the BBC revival of University Challenge began.

A 1996 edition of the programme featured contenders from all corners of the UK, as Magnus was keen to point out in his introductory spiel: an Irishman, a Scotsman, an Englishman and a Welsh woman. The Irishman, Robert Devlin, and the Scotsman, Dr Malcolm Walker-Kinnear, went through to the next round as winner and highest-scoring runner-up respectively. Similarly, the winners of the Junior series represented three of the four corners of the UK: the 2004 winner, Daniel Parker, was from Wales, the 2006 winner, Domnhall Ryan, was from Northern Ireland, while the remaining three, Robin Geddes, Robert Stutter and David Verghese, were all from England.

There has always been a considerable University Challenge/'Mastermind'-crossover, with many contestants from the former going on to take part in the latter (and occasionally vice versa), but 'Mastermind's' 2010 Grand Final almost certainly holds the record for the greatest number of former UC contestants competing in one edition of 'Mastermind'. The series winner, Jesse Honey, had been part of the Durham University team that had reached the UC semi-finals in 1999. Kathryn Johnson, who finished in second place, had been a member of the victorious British Library team in the 2004 UC 'Professionals' series. Barbara Thompson had been the captain of the Open University team that had won the 1985 UC series and had also reached the semi-finals in the 2002 'Reunited' series. Finally, Les Morrell had competed in the 2004/5 UC series as part of an East Anglia University team, who reached the second round. In addition, one other contestant, Mark Grant, was appearing in his second "Mastermind" Grand Final, having previously achieved the feat in 2005. The 2011 champion, Dr Ian Bayley, had previously been a contestant twice on 'University Challenge', reaching the second round on his first appearance (on behalf of Imperial College, London, in 1996) and the quarter-finals the second time (on behalf of Balliol College, Oxford, in 2001). Bayley later went on to become a 'Mastermind' finallist in 2009 and was narrowly beaten by Nancy Dickmann, which made him all the more determined to go one better in the 2011 series. (Oh, and he'd also previously won 'Brain of Britain', as Humphrys pointed out when presenting Bayley with the 'Mastermind' trophy).

The rules were changed in 1995 to allow previous contenders, except finalists, to return. This has since been changed again to allow defeated finalists another go as well. Isabelle Heward has been a contender four times (1983, 1996, 2003, 2005) and reached the semi-finals on each of her last three entries. All of her specialist subjects have been related to the cinema. Sheila Altree has also appeared in four series (1980, 1985, 1997, 2007), the first time under her first married name, Sheila Denyer. She won her heat in 1985 before someone tipped off the producers that Altree and Denyer were the same person and they disqualified her. Geoff Thomas won the title at his fourth attempt: he was a semi-finalist in 1994 and again in 2001's one-off Discovery Mastermind series, runner-up in 2003 and finally champion in 2006.

A panel of clergy contested a heat at Norwich Cathedral in 1996 and the winner, Dr Richard Sturch, went on to win that series' grand final. When he returned for the 2010 'Champion of Champions' series, Sturch revealed that he had originally gone on mainly because, at the time, the clergy had not been getting a very good press within the field of quizzing and other aspects of popular culture, so he had wanted to try to redress the balance, as did the 'Mastermind' team, which was why they had decided to have an all-clergymen edition. However, it's also worth noting that the famous 'showbiz vicar', the Reverend David Smith, was still very active in the quizzing world at the time: he had always proved highly entertaining and knowledgeable in all the (many) shows he had been on.

In 1987, married couple Paul and Christine Hancock competed in the same edition of the show. Both scored 34 correct answers and two passes; Mr. Hancock won the play-off by one question. Magnus very appropriately entitled that edition 'Hancock's Half-Hour'. The couple also later appeared on Masterteam, along with Mr Hancock's brother.

Similarly, a father and son who appeared on the programme were Ashok Venkatesh, who had been a finallist in the 2006 regular series, and his son, Nikhil, who had previously done well in his first round match in that year's 'Junior' series.

Another family event occurred during the two 2007 series of Junior Mastermind. In the series screened early that year, twins Robert and Tintin (real name Antonia) Stutter competed in separate heats. Although they both scored impressively, only Robert made it into the Grand Final, which he duly won - with the specialised subject of Tintin, appropriately enough. Their younger brother Edmund took part in the later series, having apparently been determined to follow in his siblings' footsteps, and also performed well: he was one of the defeated finallists. Had he won, he would have received the trophy from his own brother, because the previous champions in that series always came to present the trophy. Previous winners also presented the trophy on several occasions during the regular series.

One of Robert's opponents in the aforementioned Grand Final, William, had interested Humphrys in his first round by answering questions (and winning the heat) on 'Hancock's Half Hour' - Humphrys was surprised that a radio comedy from so long ago held the interest of such a young contender. It also transpired that William listened to the 'Today' programme, much to Humphrys's delight - but in fact, the only reason for that was the fact that the lad's parents insisted on listening to said programme while driving him to school and, as he was always sat in the back of the car, he could not change the channel. Oh well, you can't win 'em all, Humphrys, eh?

Another memorable moment from 'Junior Mastermind' was just after the last (so far) champion, David Verghese, had been presented with his trophy by the aforementioned Robert: Humphrys asked David what he hoped to do next and the latter stated that, as soon as he was old enough, he wanted to go on University Challenge, adult Mastermind and Who Wants to be a Millionaire? Humphrys duly wished him luck with all that.

Celebrities

Many of the celebrities' appearances on their version of the show proved memorable. Vic Reeves did a silly walk to the black chair and Magnus (rather sourly) asked him, "Occupation? - as if I needed to ask."

When John Humphrys asked Edward Stourton for his name, Stourton responded in mock-indignation, "John - we practically sleep together!" (A bit too much information there, maybe, but he was, of course, referring to the fact that he and Humphrys work together on the 'Today' programme).

When Peter Serafinowicz was presented with his trophy, he returned to the black chair and pretended to drop off to sleep, as if indicating that the whole experience was a very draining one. Humphrys was somewhat nonplussed and tried nudging him - but to no avail.

When Bernard Cribbins appeared, Humphrys asked him to do a 'Wombles'-narration, which he was famous for doing in the 70's - Cribbins duly obliged with his usual great aplomb, finishing with, "John - go out and collect any old rubbish you can, but John - don't bring her back to the burrow!" (Nice one).

Humphrys also asked Tim Vine to do his most famous trick of telling as many jokes as he could in a short space of time (probably one minute in this case?) and, like Cribbins, Vine certainly did not disappoint us. In addition, thanks to Humphrys, we got to find out how Spoony got his nickname - apparently, his head was shaped like a spoon when he was a kid.

We also found out that the veteran quiz host and producer William G. Stewart found asking the questions much easier than answering them - and, when Humphrys asked his former "Nine O'Clock News" colleague, Julia Somerville, why she had chosen 'Winnie The Pooh' as a specialist subject, she responded, "I just wanted to hear a distinguished journalist like you talk about Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore and Tigger". (Why not indeed?)

A classic moment occurred in the all-comedians 2009 Children In Need special, when Stephen K Amos scored 5 points with 5 passes on his specialist subject, which just happened to be Five Star, the 1980s pop group! Amos then went on to achieve an equally appropriate final score of 15, admittedly with a bit of help from Humphrys, but rightly so in this case.

Soon after this, when Michael Winner appeared, he failed to live up to his name (quite the reverse, in fact) and even resorted to constantly asking Humphrys, "Can I ask the audience?" and "Can I phone a friend?" etc etc. (Actually, it was nice to see Winner showing a sense of humour, rather than his usual abrasive persona).

In the 2010 Children In Need Special, Stewart Francis told Humphrys, "You look like a much younger person". "I wish I could say the same for you", answered Humphrys, then Francis added, "I was talking to Pudsey", (who, of course, was sitting strategically on Humphrys's desk). Humphrys decided to move swiftly on.

When Humphrys presented the trophy to Hilary Kay in a 2010 Celebrity edition, he asked her to give a valuation for said trophy, much as she would in her main show, The Antiques Roadshow. Kay responded, in her usual style, "Well, how much would you say it's worth?" "You were meant to say, 'It's priceless'!" exclaimed Humphrys in mock-indignation, and Kay was quick to answer, "Oh, it's definitely that", much to Humphrys' relief.

On another 2010 Celebrity edition, David Threlfall was answering questions on the Bonzo Dog Band. One question (enquiring after the title of their 2007 reunion album) had to be answered in French (Pour l'Amour des Chiens) and he failed to do so, but was most indignant when Humphrys took it as a pass. At the end of his round, Threlfall protested that he knew what it was but just couldn't manage the French pronunciation. "Yes, it is a problem, but it's actually your problem, not mine", declared Humphrys, with some severity. Threlfall still looked and sounded disgruntled, although he appeared slightly mollified when he found out that he'd scored 12 points. "And our final contender, please - and I hope that he's going to be less trouble than the last one", was Humphrys' parting shot. Humphrys' apparent rudeness was explained and excused when Threlfall returned for his General Knowledge questions and their chat revealed that Humphrys and Threlfall knew each other from the school run, as their children went to the same school.

Actor Rhys Thomas not only scored a (celebrity) record 21 points on his specialist subject, the rock group Queen, but did so dressed in a replica of Freddie Mercury's famous harlequin costume, much to Humphrys' amusement.

Oh, and let's not forget that classic moment when "Dad's Army's" Ian Lavender had just sat down in the black chair: Humphrys asked him his name and one of Lavender's opponents, Rick Wakeman, called out that immortal line, "Don't tell him, Pike!" with immaculate timing and to the great amusement of all concerned. "Yes, we let anyone on this show nowadays", chuckled Humphrys.

Questions and Answers

Over 57,000 questions were asked over the course of the original series.

The last ever question asked on the Magnus version of the programme was virtually the same as the first one asked back in 1972 (concerning Picasso's Guernica). This was plotted beforehand as an in-joke to be played only if the scores did not depend on it.

In 1996, one contender took The Sex Pistols as a specialist subject, but the BBC insisted that the word "bollocks" (as in "Never Mind the...") be bleeped out of the broadcast. According to question-setter Elizabeth Salmon, this was the first and only time a question on the show was censored in this way.

Magnus Magnusson claimed that he once got a letter from an irate viewer who accused him of blasphemy for saying that Jesus' first name was Reginald. It turned out that the correspondent had actually misheard a question concerning Jeeves's first name!

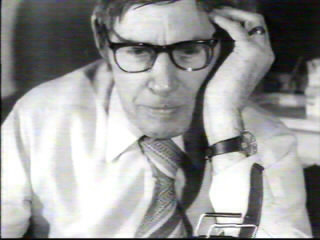

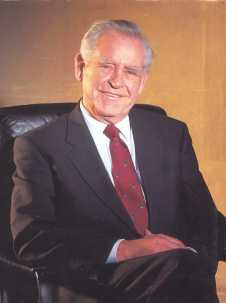

Magnus Magnusson, not the sort to confuse Jeeves with Jesus

Magnus Magnusson, not the sort to confuse Jeeves with JesusWith the many hundreds, if not thousands of questions asked each series, it's perhaps inevitable an incorrect question will slip through now and again. In one episode in February 2010, a contender was asked of which African country was Janet Jagan the president between 1997-1999. The contender guessed Ghana, but was told the answer was Guyana - which is in fact a South American country. The contender in question ultimately finished in last place however, some 13 points behind the winner, and 6 points behind their nearest competitor, meaning it didn't materially affect the game.

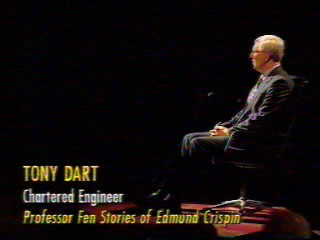

In a heat in 1997, Colin Cadby was judged to have given an incorrect answer to a question when he had actually got it correct. He ended up losing to Tony Dart - however, he qualified as one of the highest-scoring losers, and ended up reaching the final (beating Dart in his semi-final).

Around 2008, John Humphrys asked the question 'Which chemical has the symbol Ti?' The contestant gave the (correct) answer 'Titanium' - however Humphrys said that the answer was 'Thallium' (he had obviously misread the lower-case L in the chemical symbol Tl as a capital I). Thankfully it made no difference to the outcome of the match.

Pleasingly, one former contender, Anna Torpey, is now a question-setter for the programme and is listed as such in the end credits. Torpey was a finallist in the 2007-8 series.

Scoring records

Low scores:

- The famous Arfor Wyn Hughes is not, and never was, Mastermind's lowest scorer - he scored 12. The lowest ever score is 5 points, achieved by Kajen Thuraaisingham in the 2009-10 series (4 points on Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and just 1 on general knowledge).

- Before this, the lowest score record for the regular (non-celebrity) series was 7 points, set by Colin Kidd in the 2005 series. He scored 4 on the history of the World Chess Championships and 3 on general knowledge. This was equalled by Michael Burton in the 2009-10 series with 2 on angels, 5 on general knowledge.

- In 2004, Gill Perry scored 8 points, 4 on her specialist subject (Babylon 5, series 1 & 2) and 4 on general knowledge.

- Previously, scores of 9 points were 'achieved' by Armando Margiotta, Sally Copeland and a community worker from Warwickshire who wishes to remain anonymous. 9 points have also been scored by Michael Kane in the 2004 final, and in 2006 by Steve Bolsover in the first round and Simon Curtis (who fell into "pass hell" and scored just one point on his specialist subject, the films of Jim Carrey) in the second. Mr Curtis was not the first contestant to score only one point on a specialist subject, however - Arabella Weir had also done so in a 2004 celebrity special, her subject having been 'Dallas' (the television series). Two other contestants to score 9 points have been Cliff Hughes and Andrew Hesford, both in the 2007 series. In the 2010 series, Paul Robson scored only 2 points on his chosen subject ('The Weimar Republic') - however, he did considerably better on general knowledge, finishing on 11 points.

- The lowest-ever score on the programme (until the aforementioned Mr Thuraaisingham's match) was achieved by both Arabella Weir and Tara Palmer-Tompkinson in the above-mentioned 2004 celebrity special: 6 points. Only the previous week, Murray Walker had scored 7 points, despite the fact that his specialist subject was 'Formula One'. Politicians had mixed fortunes - David Blunkett and Gyles Brandreth both only scored 11, Neil Hamilton, David Lammy and Michael Howard did slightly better, Lembit Opik and Diane Abbott better still and Edwina Currie won her game.

High scores:

- The highest score was 41, set by Kevin Ashman in 1995. Jennifer Keaveney, Mary Elizabeth Raw and Anne Ashurst all scored 40. Keaveney did so twice. Prior to Keaveney setting the new record in 1986, the highest-ever score was 38, achieved by the 1984 champion Margaret Harris in that series' Grand Final. 38 is also the highest score in the Humphrys era, which was achieved by Jesse Honey in the heats of the 2010 'Champion of Champions' series - beating his own record of 37 set in the 2010 Grand Final. Before this, the revival record was 36 points, earned by Geoff Thomas in the 2006 Grand Final.

- The 2010-11 series changed the format a little, with the heats and final having the general knowledge round extended to two and a half minutes, meaning scores are not directly comparable to those in earlier series. The highest score to date in the extended format is Ian Bayley's 37 points in the 2011 Grand Final. Brian Pendreigh had previously came close in the heats by scoring 35 points, his chosen subject having been The Beatles. In the same series, two other contenders, Keith Nickless and Nick Mills, tied on 34 points, with Nickless winning the game on passes. Mills, it should also be noted, was an impressive former University Challenge contestant, having the been the captain (and star player) of a Manchester University team that made it as far as the semi-finals in the 2004/5 series. (See also 'Trivia - Contenders' below). Strangely enough, Mills and Nickless went on to appear in the same semi-final, in which they did not score quite so highly (due in part to there being less time available to each contender - 3½ minutes rather than the 4½ minutes in the heats) and this time Mills outscored Nickless, but was himself beaten by another contender, Peter Riley, who went on to finish in second place in the Grand Final.

Jesse Honey's revival high-score of 38. The contender on the left (with 28 points) is previous revival record-holder Geoff Thomas. The other two contenders are the 1987 champion Dr Jeremy Bradbrooke (with 25 points) and the 1991 winner Stephen Allen (with 29 points)

Jesse Honey's revival high-score of 38. The contender on the left (with 28 points) is previous revival record-holder Geoff Thomas. The other two contenders are the 1987 champion Dr Jeremy Bradbrooke (with 25 points) and the 1991 winner Stephen Allen (with 29 points)- Jesse Honey's 38 points included the all-time record score in a specialised subjects round: 23 points on Flags of the World. The previous record was set in 1979 when Joe West, a helicopter pilot from Shetland, scored 22 points on the life of Lord Nelson. The highest score in that round in the Junior series was scored in the early-2007 Grand Final by a boy named Callum: he scored 19 points on the life and career of the cricketer Andrew Flintoff, but was narrowly beaten in the General Knowledge round.

- Even allowing for the fact that celeb participants aren't subjected to quite as hard a challenge as regular contenders, the 2010-11 yuletide Celebrity Mastermind series saw some very impressive performances. Frank Gardener scored 20 in his general knowledge round, which has to be one of the highest scores for that round, though this was presumably equalled and/or beaten on several editions of the regular series - and almost certainly by Kevin Ashman when he achieved his record-breaking score of 41 points. And Rhys Thomas racked up a magnificent 21 points in his specialist round, on the group Queen.

- The highest score for the Celebrity version of the show, 36 points, was achieved by Hilary Kay and matched by Rhys Thomas in two separate 2010 editions. One of Kay's opponents, Richard Herring, equalled the previous record, which had been set by Lucy Porter in the 2009 Comedians Special for Children in Need: 35 points. Mark Watson had been close behind Porter in the latter edition with 33: this score was matched in 2011 by Lord Digby Jones. Prior to these records being set, the highest score for this version of the show had probably been the one achieved by Tom Ward in 2005: 31 points.

Other:

- In a 2005 celebrity special, former Popstars winner Myleene Klass may have set a record for the most asynchronous performance - scoring 17 points from 18 questions about Sex & The City series 3, but only answering one question right in the general knowledge round. A contender on the 2003 regular series did something similar (if not quite on the same scale), scoring 12 points on the Harry Potter films (of which there were only two at the time), but only getting one right in her general knowledge round.

Production notes

By 1981 the programme had visited every British university, with Aberdeen the last to play host to the show.

One venue that provided some very interesting scenery was the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu, Hampshire, which played host to the show in 1983: it was certainly refreshingly different to see the contenders competing amid a collection of vintage vehicles. The same museum reappeared 21 years later on the first 'Junior Mastermind' Grand Final - not as a venue for the programme, but as the place where the eventual winner, Daniel Parker, had gone to research his chosen subject. That subject was 'James Bond Villains', although one would suspect that the museum was actually a more obvious research-venue for his previous subject, namely 'The Volkswagen Beetle'. (Not that it ultimately mattered in any case: he won the series in considerable style).

Though the regular series is produced in Manchester, the celebrity version is made (for now at least) at BBC TV Centre in London.

Magnus-era scorekeeper Mary Craig also filled the same role on Television Top of the Form and its international spin-off Transworld Top Team.

In the Magnus Magnusson years, the questions and responses were carefully measured to give an optimum 20 questions per two-minute round. Each contestant's general knowledge round included one question about their home region, history, geography, literature, and science. According to question setter Janet Barker in a Radio Times article in 2010, modern general knowledge rounds take the individual contenders' backgrounds into account: "if someone’s got a career in science they might have a slightly harder one [on science] in their general knowledge than someone who was a musician."

In some of the early finals, the rounds were extended to three minutes. In the second round of the 2010 series, the specialist rounds were shortened to 90 seconds in order to cram five contenders into the regular half-hour slot (a format which has been retained for the 2010-11 semi-finals). The 2010-11 series has also seen the general knowledge round extended to two and a half minutes in the heats, yet, bizarrely, this did not happen in any of the subsequent celebrity matches, in which the general knowledge round went back to the original two minutes. Actually, this may have been because Humphrys still chats to the celebrities between the rounds, which he no longer does with the regular series contenders.

Although Junior Mastermind did not make its debut until 2004, there had been a few children's versions of Mastermind during the Magnus-era. Around 1980/81, a special edition was made on Jim'll Fix It with a girl answering questions on the 'Mister Men' books by Roger Hargreaves: she achieved a very impressive score. There had also been a special edition screened as part of one of the BBC's Saturday morning programmes (either 'Swap Shop' or 'Saturday Superstore') around 1981/82. In addition, the show was amusingly mentioned on an early edition of The Vicar of Dibley, in which Geraldine (alias Dawn French) was telling her congregation that she'd once wanted to go on 'Mastermind', but had been unable to, partly because she was too young (at only four and a half) and partly because there wasn't much call for "The Wombles" as a specialist subject. Not at that time, maybe, but of course 'Junior Mastermind' started some ten years later - and, soon after that, on the regular series, one contender answered questions (which were actually quite hard) on "The Trumptonshire Trilogy", ie the Brian Cant-narrated kids' series, "Camberwick Green", "Trumpton" and "Chigley". As a minor footnote to this, when a contender on the 2005 Junior series took The Vicar of Dibley as a specialist subject, the question-setters couldn't resist a cheeky bit of self-reference and included one asking for Geraldine's proposed specialist subject - which, we're pleased to report, the contender, Robin Geddes, (who went on to win the series) got right.

An equally cheeky piece of self-reference occurred on another episode of the same series, when one contestant, James, was answering questions on "Fawlty Towers". During his chat with James in between the two rounds, Humphrys referred to the moment in the comedy when Basil told Sybil that she should go on "Mastermind" and that her specialist subject should be 'The Bleeding Obvious' - and James (not surprisingly, given that he had gained a high score on the subject) knew it well. This was actually used as a question in the 2010 Children In Need Celebrity Special, in which Fred MacAulay was also answering questions on 'Fawlty Towers' (or as the onscreen caption had it, "Farty Towels"), and he got it right too. Oh, and just to keep up the self-reference theme, MacAulay's general knowledge round also included the question, "Which comedy duo once performed a 'Mastermind' sketch with the specialist subject being 'Answering the Question Before Last'?" and he got that one right too - the answer being 'The Two Ronnies', of course.

There was a Doctor Who special in 2005, with Christopher Eccleston awarding the trophy. Eccleston also appeared on 'Junior Mastermind' the following year, offering help and encouragement to one of the finallists, Sam, who was answering questions on the former's 'Doctor Who' series. (Sam, by the way, turned out to be the grandson of the late and legendary cricket commentator Brian ('Johnners') Johnston, and John Humphrys was only too keen to talk with Sam about Johnners' most famous line, "The bowler's Holding, the batsman's Willey".)

Throughout most of the Magnus-years, Magnus would tell contenders who had passed their score, followed by an initial round of applause, then he would go through the passes, while those who hadn't would be told their score, followed by "And no passes - thank you very much". From time to time, the contenders who had passed would make to leave, thinking they had no passes, then do a double take and sit back down again and Magnus would usually say (humorously), "And just before you dash away, let me give you your (however many) passes..." One contender in the 1986 series, however, was so convinced that he had no passes that he actually returned to his seat and Magnus had to call him back. Probably as a result of this, the system later changed so that Magnus would announce the score, immediately followed by the number of passes (if any), so that there could be no doubt on the matter. The system was tweaked again when John Humphrys took over: he always deals with the passes before announcing the score.

A modified version of the Mastermind format was used for the US sports quiz series 2 Minute Drill (2000-1). Confusingly, there has since been a US quiz show called MasterMinds, which isn't based on this programme, but is rather a version of the College Bowl (UK: University Challenge) format.

There was also a version in the Netherlands, called Megabrein. Marga Scott-Johnson tells us:

- Sadly, it only ran for two seasons (1991-2 and 1992-3) due to disappointing viewing figures. I took part in the 1992-3 series and made it to the semi-final. In fact, taking part in Megabrein completely changed my life, as I met my first husband (Keith Scott, a contender on Mastermind in 1987 and 1995) through the Mastermind Club in the UK and as a result have lived in Britain since 1999!

Magnus Magnusson on one of Esther Rantzen's chat shows revealed that Mastermind's success was due in part to TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse. Mastermind was originally intentioned as a quiz for "insomniac academics" and shown in an appropriately late-night slot (around 10.15pm most weeks, with a daytime repeat later in the week, around 3.30pm). In 1973 the BBC were showing a sitcom called Casanova '73, written by Galton & Simpson and starring Leslie Phillips in full-on "hellllo laydees" mode. It wasn't exactly The Borgias, but nevertheless Whitehouse cast a glance at the BBC and they moved it past the watershed, leaving the way clear for Mastermind to fill the plum 8pm slot, right after Top of the Pops. And the rest, as they say, is history. So there we are.

Some of the show's 1996 editions were screened back-to-back with a very different show, namely Small Talk and the BBC produced an amusing trailer for both shows as a result. Magnus's voice would be heard saying, "May I have our first contender, please?" and a little boy would appear and announce, "My name's Jamie, I'm six years old and I'm a genius". Magnus would then ask, "Occupation?" and a little girl would say, "I can do a magic trick - watch!" (This 'trick' was putting a pencil on her top lip as a moustache - and the pencil duly fell off, surprise, surprise!) Finally, Magnus would ask, "And your chosen specialised subject?" and a rather serious little boy would say, "Er - I'm not sure about that question". A clever way of trailering two very contrasting shows and certainly a cut above the average BBC trailer.

The black chair was voted the second most iconic chair of the 20th century in a 2009 survey for House Beautiful magazine. Now that's trivial! It was beaten to the top spot by the copy of an Arne Jacobsen model 3107 from that famous photo of Christine Keeler. Should you want to buy one to intimidate your house guests, you may wish to know that the current chair is an Eames Soft Pad Chair made by Herman Miller. The one used on TV is specially modified, with detachable arms (in case a contender is too large to fit between them) and four feet instead of the usual five.

Champions

Winners are listed with their specialist subjects. Before 1992, contenders could revert to their original subject for the final if they so wished. Discovery Mastermind, Junior Mastermind and Mastermind Cymru did not have a semi-final phase. There were two Junior Mastermind series in 2007. The 2007 Mastermind Series ran on into 2008.

| Regular series | ||||

| Year | Name | Heat | Semi-final | Final |

| 1972 | Nancy Wilkinson | French Literature | European antiques | History of music 1550-1900 |

| 1973 | Patricia Owen | Grand Opera | Byzantine art | Grand Opera |

| 1974 | Elizabeth Horrocks | Shakespeare's plays | Works of JRR Tolkein | Works of Dorothy L Sayers |

| 1975 | John Hart | Athens 500-400 BC | Rome 100-1 BC | Athens 500-400 BC |

| 1976 | Roger Prichard | Duke of Wellington | 20th Century British warships | Duke of Wellington |

| 1977 | Sir David Hunt | WW2 British campaigns in N.Africa | WW2 Allied campaign in Italy | Roman Revolution 60-14 BC |

| 1978 | Rosemary James | Roman & Greek mythology | Works of Frederick Wolfe | Roman & Greek mythology |

| 1979 | Philip Jenkins | Christianity 30-150 AD | Vikings in Scotland & Ireland 800-1150 AD | History of Wales 400-1100 AD |

| 1980 | Fred Housego | King Henry II | Westminster Abbey | The Tower of London |

| 1981 | Leslie Grout | St George's Chapel Windsor | Burial Grounds of London | St George's Chapel Windsor |

| 1983 | Christopher Hughes | British Steam Locomotives 1900-63 | The Flashman novels | British Steam Locomotives 1900-63 |

| 1984 | Margaret Harris | Cecil Rhodes | Postal history of Southern Africa | Cecil Rhodes |

| 1985 | Ian Meadows | English Civil War | History of Astronomy to 1700 | English Civil War |

| 1986 | Jennifer Keaveney | Elizabeth Gaskell | E. Nesbitt | Elizabeth Gaskell |

| 1987 | Dr Jeremy Bradbrooke | Franco-Prussian War | Anglo-American War 1812-15 | Crimean War |

| 1988 | David Beamish | Nancy Astor | British Royal Family 1714-1910 | Nancy Astor |

| 1989 | Mary Elizabeth Raw | Charles I | Prince Albert | Charles I |

| 1990 | David Edwards | Michael Faraday | Benjamin Thompson, Count Romford | James Clerk Maxwell |

| 1991 | Stephen Allen | Henry VII | Dartmoor & its environs | Sir Francis Drake |

| 1992 | Steve Williams | Surrealist art 1918-1939 | Peter the Great | Post-Socratic Philosophy |

| 1993 | Gavin Fuller | Doctor Who | The Medieval Castle in the British Isles | The Crusades |

| 1994 | Dr George Davidson | English coinage 1066-1662 | History of Chemistry 1500-1870 | John Dalton |

| 1995 | Kevin Ashman | Martin Luther King | History of the Western film | The Zulu War |

| 1996 | The Reverend Dr Richard Sturch | Charles Williams | Emperor Frederick III | Operas of Gilbert and Sullivan |

| 1997 | Anne Ashurst | Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset | Regency Novels of Georgette Heyer | Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland |

| Radio 4 version | ||||

| 1998 | Robert Gibson | The Solar System | Charles II | Robert The Bruce |

| 1999 | Christopher Carter | Birds of Europe | The House of Tudor | British customs and traditions |

| 2000 | Stephen Follows | Benjamin Britten | T.S. Eliot | Leos Janacek |

| Discovery Mastermind | ||||

| 2001 | Michael Penrice | Professional Boxing to 1980 | (no semi-final) | English History 1603-1714 |

| BBC Revival | ||||

| 2003 | Andy Page | The Academy Awards | Gilbert and Sullivan | Golfing majors since 1970 |

| 2004 | Shaun Wallace | European Champions League Finals since 1970 | English football team at the European Championships since 1960 | FA Cup finals since 1970 |

| 2005 | Patrick Gibson | The films of Quentin Tarantino | The Culture novels of Iain M. Banks | Father Ted |

| 2006 | Geoff Thomas | Edith Piaf | William Joyce | Margaret Mitchell |

| 2008 | David Clark | Henry Ford | The Prince Regent | History of London Bridge |

| 2009 | Nancy Dickmann | The Amelia Peabody novels | Life and German films of Fritz Lang | The Lewis and Clark Expedition |

| 2010 | Jesse Honey | The London borough of Wandsworth | Antoni Gaudi | Liverpool Anglican Cathedral |

| 2011 | Dr Ian Bayley | Romanov Dynasty 1613-1917 | Jean Sibelius | Pictures in the National Gallery |

| Champion of Champions | ||||

| 1982 | Sir David Hunt | History of Crete | (no semi-final) | Alexander the Great |

| 2010 | Pat Gibson | The films of Pixar | (no semi-final) | Great mathematicians |

| Junior Mastermind | ||||

| 2004 | Daniel Parker | Volkswagen Beetle | (no semi-final) | James Bond villains |

| 2005 | Robin Geddes | The Vicar of Dibley | (no semi-final) | A Series of Unfortunate Events |

| 2006 | Domhnall Ryan | The Spitfire | (no semi-final) | Animals of the African plains |

| 2007 | Robert Stutter | Madame Tussaud | (no semi-final) | Tintin |

| 2007 | David Verghese | The Jurassic Park films | (no semi-final) | George Lucas |

| Mastermind Cymru | ||||

| 2006 | Emyr Rhys Jones | The Simpsons | (no semi-final) | The Eurovision Song Contest to 1990 |

| 2007 | Siôn Aled | Welsh Religious Revival of 1904-06 | (no semi-final) | Life and poetry of Goronwy Owen |

| Mastermind Plant Cymru | ||||

| 2008/9 | Seren Jones | Doctor Who revival series 3 | (no semi-final) | St. Clears books by Enid Blyton |

| 2009 | Joseff Glyn Owen | Cyfres Gwaed Oer | (no semi-final) | C'mon Midffild |

| Sport Mastermind | ||||

| 2008 | Chris Bell | British and Irish Lions | (no semi-final) | Life and career of Geoffrey Boycott |

Mastermind International

1979 John Mulcahy (Ireland): Irish History (1916-22)

1980 Rachel "Ray" Stewart (Australia): Life and times of Julius Caesar

1981 David Harvey (New Zealand): The Lord of the Rings trilogy

1982 Leslie Grout (UK): Windsor Castle

1983 Christopher Hughes (UK): British Steam Locomotives

Celebrity Mastermind

The following have won their respective show, which is not in a tournament format:

Jonathan Meades

Shaun Williamson

Bill Oddie

Stephen Fry

Edwina Currie

Matt Allwright

Steve Rider

Hugh Quarshie

Tom Ward

Jeremy Beadle

Monty Don

Graham Le Saux

Paul Ross

Iain Banks

Steven Pinder

Edward Stourton

Todd Carty

Iain Lee

Dave Spikey

Peter Serafinowicz

Jan Ravens

Steve Cram

Spoony

Kaye Adams

Dave Myers

Philippa Gregory

John Sessions

Sally Lindsay

Tim Vine

Lucy Porter (2009 Children in Need Special)

Loyd Grossman

Stuart Maconie

Alastair Stewart

Tony Audenshaw

Tristan Gemmill

Stewart Lee

Paul Gambaccini

John Bird

Nigel Planer

Beverley Knight

Andi Osho (2010 Children in Need Special)

Hilary Kay

Samira Ahmed

Frank Gardener

Hattie Hayridge

Rhys Thomas

Stephen Mangan

Michael Buerk

Lord Digby Jones

Brian Moore

Seeta Indrani

Specials

Doctor Who special: Karen Davies

Merchandise

I've Started So I'll Finish - The Story of Mastermind by Magnus Magnusson (ISBN: 0-316-64132-4) is an exhaustive account of the programme, by the person who knew it best.

Mastermind CD-ROM game for Windows 95/98

Web links

BBC: Junior Mastermind 2005 press release and 5min showreel

BBC: Junior Mastermind 2004 showreel (Real Media)

Videos

We also have the script from the extended stage version of this sketch for you to read.

See also

Hobby Horse, a short-lived team version for children.

How to apply

Prospective contenders can fill in the online application form or write to:

Mastermind Room 4012 New Broadcasting House Oxford Road MANCHESTER M60 1SJ

Application details are provided as a service to readers, but please note that all contestant enquiries should be directed to the named production company and not to UKGameshows.com. Addresses can be found on our list of contact details for production companies.