Eurovision Song Contest

(→Web links) |

(→See also) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

[[Ken Bruce]] (1988-2022)<br> | [[Ken Bruce]] (1988-2022)<br> | ||

[[Scott Mills]] (2023-)<br> | [[Scott Mills]] (2023-)<br> | ||

| - | [[Rylan Clark-Neal]] (2023-) | + | [[Rylan Clark-Neal]] (2023-) |

Semi-Final commentators:<br> | Semi-Final commentators:<br> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

[[Laura Whitmore]] (2014)<br> | [[Laura Whitmore]] (2014)<br> | ||

[[Mel Giedroyc]] (2015-17)<br> | [[Mel Giedroyc]] (2015-17)<br> | ||

| - | [[Rylan Clark-Neal]] (2018-19, 22-) | + | [[Rylan Clark-Neal]] (2018-19, 22-)<br> |

| + | Richie Anderson (Radio: 2024) | ||

== Broadcast == | == Broadcast == | ||

| Line 110: | Line 111: | ||

''Cliff Richard, who controversially came second with "Congratulations" despite being heavily tipped to win''</div> | ''Cliff Richard, who controversially came second with "Congratulations" despite being heavily tipped to win''</div> | ||

| - | Each grand show has its own distinctive style depending on where it's being held each year. The hosts always speak in English and French with some usage of other languages too. After the opening spiel we get on to the songs. Before each song there's normally a little piece of PR film saying "look how great your host country is!" which seem to have some effort put into them and yet make no sense whatsoever. Look! There's a man fishing (connotation: Look! We might be a modern country, but we still do traditional stuff), but he's quite obviously staring at that castle over there. Zooming into the castle (connotation: Look! We have old buildings!), there's a bloke using a big computer (connotation: look how technologically advanced we are! Compare that to our traditional methods!) then he'll makes some whizzy lines jump out of the screen which will whizz round and form pictures of the members of the band about to perform. Zoom out of the band to find out that the band were in fact in the fisherman's eye. Continue zooming out to see the fisherman. The fisherman catches something - it's the flag of the next country up! Marvellous. Alright so we made that up, but it's not too far from the truth. | + | Each grand show has its own distinctive style depending on where it's being held each year. The hosts always speak in English and French with some usage of other languages too. After the opening spiel we get on to the songs. Before each song, there's normally a so-called "postcard" - a little piece of PR film saying "look how great your host country is!" which seem to have some effort put into them and yet make no sense whatsoever. Look! There's a man fishing (connotation: Look! We might be a modern country, but we still do traditional stuff), but he's quite obviously staring at that castle over there. Zooming into the castle (connotation: Look! We have old buildings!), there's a bloke using a big computer (connotation: look how technologically advanced we are! Compare that to our traditional methods!) then he'll makes some whizzy lines jump out of the screen which will whizz round and form pictures of the members of the band about to perform. Zoom out of the band to find out that the band were in fact in the fisherman's eye. Continue zooming out to see the fisherman. The fisherman catches something - it's the flag of the next country up! Marvellous. Alright, so we made that up, but it's not too far from the truth. |

<div class="image"><IMG src="/atoz/programmes/e/eurovision_song_contest/eurovision_2.jpg" width="300" height="225" border="0"> | <div class="image"><IMG src="/atoz/programmes/e/eurovision_song_contest/eurovision_2.jpg" width="300" height="225" border="0"> | ||

| Line 174: | Line 175: | ||

In 1996, the "relegation" system was replaced by a non-televised audio-only qualifying round and juries had to choose twenty-two out of the twenty-nine participants to go through to the actual final. This proved unpopular with the competing countries and the "relegation" system was brought back the following year in 1997, but this time the bottom seven countries that received the lowest "average" scores in the past five contests (participated or not) have to sit out in the next contest. The host country would always take part, even if their average wouldn't otherwise qualify. | In 1996, the "relegation" system was replaced by a non-televised audio-only qualifying round and juries had to choose twenty-two out of the twenty-nine participants to go through to the actual final. This proved unpopular with the competing countries and the "relegation" system was brought back the following year in 1997, but this time the bottom seven countries that received the lowest "average" scores in the past five contests (participated or not) have to sit out in the next contest. The host country would always take part, even if their average wouldn't otherwise qualify. | ||

| - | Also in 1997, for the first time ever, the European public got to vote for their favourites! Televoting was trialled in five of the participating countries | + | Also in 1997, for the first time ever, the European public got to vote for their favourites! Televoting was trialled in five of the participating countries (the UK, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Sweden). The trial proved so successful that televoting became the rule for every country in 1998 (though everyone had the option to use a mixture of televote-and-jury in 2001 and 2002). Countries with poor telephone networks continued to use juries, and the jury would step in when a televote failed for whatever reason. No longer would the most jury-friendly song win, but victory would now go to the most popular song amongst the public. |

| - | Two | + | Two fundamental changes were made in 1999. Out went the orchestra, the songs now being performed with backing tracks. And out went the rule dictating that a song had to be sung in the language, or one of the languages, of the country - it was now whatever language the country liked (in most cases English). |

With France facing relegation in 2000, an exemption was introduced for the "Big Four" - the four broadcasters who made the biggest financial contributions to the EBU would automatically qualify to the contest. They were Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and - oh, look! - France. | With France facing relegation in 2000, an exemption was introduced for the "Big Four" - the four broadcasters who made the biggest financial contributions to the EBU would automatically qualify to the contest. They were Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and - oh, look! - France. | ||

| Line 193: | Line 194: | ||

A couple of changes in the voting system came in for the 2023 contest. Viewers in countries not taking part in the contest could vote online in both the Semi-Finals and the Grand Final - at a whopping €0.99 per vote. The second change is the semi-finals are now 100% televoting, juries were only used if a televote fails. The voting in the Grand Final remained unchanged. | A couple of changes in the voting system came in for the 2023 contest. Viewers in countries not taking part in the contest could vote online in both the Semi-Finals and the Grand Final - at a whopping €0.99 per vote. The second change is the semi-finals are now 100% televoting, juries were only used if a televote fails. The voting in the Grand Final remained unchanged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Three more changes were made for the 2024 contest: the Big Five and the host nation would now perform their entries in full live during the semi-finals (in previous years we'd only seen short clips from the rehearsals of these songs), the draw for the Grand Final now has a third option called "producer's choice" which means that the host broadcaster gets free will on whichever half the qualifiers from the semi-finals will perform and the voting window in the Grand Final now opens before the first song was performed (returning to the format used in 2010 and 2011; voting in other years only began after all the songs had been performed). | ||

=== Moving and grooving with the times === | === Moving and grooving with the times === | ||

| - | The Eurovision Song Contest sharpened its act at the start of the 2010s and became more relevant by | + | The Eurovision Song Contest sharpened its act at the start of the 2010s and became more relevant. Year by year, we saw fewer clichéd joke entries and more songs from many diverse genres. Winners like "Satellite" and "Euphoria" became cherished hits across the continent. It drew star presenters and well-known interval acts like Justin Timberlake. Some broadcasters found a niche - Moldova's entries were fun and upbeat, Dutch songs tended to be sombre and reflective. |

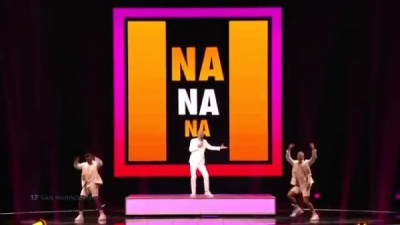

<div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2011 Moldova.jpg|400px]]''Another understated entry from Moldova.''</div> | <div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2011 Moldova.jpg|400px]]''Another understated entry from Moldova.''</div> | ||

| Line 208: | Line 211: | ||

<div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2019 san marino.jpg|400px]]''Serhat making history with San Marino qualifying for a second time in 2019.''</div> | <div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2019 san marino.jpg|400px]]''Serhat making history with San Marino qualifying for a second time in 2019.''</div> | ||

| - | As the contest approaches its platinum anniversary in | + | As the contest approaches its platinum anniversary in 2026, the Eurovision Song Contest looked in better shape than ever. It had given us worldwide success "Arcade", and followed it up with champion band Måneskin. The show's place was assured - whether as a cultural icon, or as an excuse for Europe to sing karaoke and get roaringly drunk together. |

<div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2023 loreen trophy.jpg|400px|Eurovision Song Contest]]''Loreen sung the winning entries in 2012 and 2023.''</div> | <div class=image>[[File:Eurovision 2023 loreen trophy.jpg|400px|Eurovision Song Contest]]''Loreen sung the winning entries in 2012 and 2023.''</div> | ||

| Line 276: | Line 279: | ||

**Jasmine Dotiwala (MTV producer and pop pundit) | **Jasmine Dotiwala (MTV producer and pop pundit) | ||

| - | From 2011 to 2015, the BBC selected the song and performer without consulting the public. The first three entrants were announced on early evening magazine programme ''The One Show''. In 2014 and 2015, the BBC Red Button spent some of its small budget on a special show to announce the competitors. ''Eurovision Reveal'' (3 March 2014) and ''Our Song for Eurovision 2015'' (7 March 2015) both featured a performance and an interview with [[Scott Mills]]. | + | From 2011 to 2015, the BBC selected the song and performer without consulting the public. The first three entrants were announced on early evening magazine programme ''The One Show''. In 2014 and 2015, the BBC Red Button spent some of its small budget on a special show to announce the competitors. ''Eurovision Reveal'' (3 March 2014) and ''Our Song for Eurovision 2015'' (7 March 2015) both featured a performance and an interview with [[Scott Mills]]. After a number of years where the song was unveiled on magazine programme ''The One Show'', the 2024 entry was premiered on ''Eurovision 2024: Graham Meets Olly'' (1 March 2024). |

| - | To mark the contest's 60th anniversary in 2015, the EBU decided to invite Australia to compete as a one-off. The contest has a loyal following Down Under, having been broadcast by SBS for over 30 years. Former ''Australian Idol'' winner Guy Sebastian was chosen to represent Australia at the final in Vienna, singing self-penned song ''Tonight Again''. It was announced that Australia would be able to defend their crown in 2016, in a European city of their choice, should they win. In the event, Sweden took home the honours, however Australia did finish in a respectable fifth place. As a result of positive feedback to Australia's participation, it was announced in November 2015 that the country would be invited to compete in the 2016 contest. However this time they would not be granted a pass to the final, and would have to take part in one of the semi-finals to secure their place in the final. | + | To mark the contest's 60th anniversary in 2015, the EBU decided to invite Australia to compete as a one-off. The contest has a loyal following Down Under, having been broadcast by SBS for over 30 years. Former ''Australian Idol'' winner Guy Sebastian was chosen to represent Australia at the final in Vienna, singing self-penned song ''Tonight Again''. It was announced that Australia would be able to defend their crown in 2016, in a European city of their choice, should they win. In the event, Sweden took home the honours, however Australia did finish in a respectable fifth place. As a result of positive feedback to Australia's participation, it was announced in November 2015 that the country would be invited to compete in the 2016 contest. However this time they would not be granted a pass to the final, and would have to take part in one of the semi-finals to secure their place in the final. They've been a regular competitor ever since. |

No contest was held in 2020 [[Impact of Covid-19|as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic]]. | No contest was held in 2020 [[Impact of Covid-19|as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic]]. | ||

| Line 286: | Line 289: | ||

== Web links == | == Web links == | ||

| - | [http:// | + | [http://eurovision.tv/ Official site] |

[http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0070hvg BBC programme page] | [http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0070hvg BBC programme page] | ||

| Line 330: | Line 333: | ||

* 2022: [[Weaver's Week 2022-05-15|Semi-final]] | [[Weaver's Week 2022-05-22|Final]] | * 2022: [[Weaver's Week 2022-05-15|Semi-final]] | [[Weaver's Week 2022-05-22|Final]] | ||

* 2023: [[Weaver's Week 2023-05-14|Liverpool report and semi-final]] | [[Weaver's Week 2023-05-21|Final]] | * 2023: [[Weaver's Week 2023-05-14|Liverpool report and semi-final]] | [[Weaver's Week 2023-05-21|Final]] | ||

| + | * 2024: [[Weaver's Week 2024-05-12|Semi-final]] | [[Weaver's Week 2024-05-19|Final]] | ||

[[Category:Variety]] | [[Category:Variety]] | ||

Current revision as of 09:22, 19 May 2024

Contents |

Host

Produced in the UK in these years:

1960: Katie Boyle (Royal Festival Hall, London)

1963: Katie Boyle (BBC TV Centre, London)

1968: Katie Boyle (Royal Albert Hall, London)

1972: Moira Shearer (Usher Hall, Edinburgh)

1974: Katie Boyle (Brighton Dome)

1977: Angela Rippon (Wembley Conference Centre, London)

1982: Jan Leeming (Harrogate conference centre)

1998: Terry Wogan and Ulrika Jonsson (National Indoor Arena, Birmingham)

2023: Alesha Dixon, Julia Sanina and Hannah Waddingham (all shows), Graham Norton (final only) (Liverpool Arena)

Co-hosts

Commentary (TV):

Wilfred Thomas (1956)

Berkeley Smith (1957)

Peter Haigh (1958)

Tom Sloan (1959, 61)

David Jacobs (1960, 62-66)

Rolf Harris (1967)

Michael Aspel (1969, 76)

David Gell (1969-70)

Dave Lee Travis (1971)

Tom Fleming (1972)

Terry Wogan (1973, 78, 80-2008)

David Vine (1974)

Pete Murray (1975, 77)

John Dunn (1979)

Graham Norton (2009-)

Mel Giedroyc (2023)

Commentary (Radio):

Tom Sloan (1957-58, 64)

Pete Murray (1959-61, 1968-69, 72-73)

Peter Haigh (1962)

Michael Aspel (1963)

David Gell (1965)

John Dunn (1966)

Richard Baker (1967)

Tony Brandon (1970)

Terry Wogan (1971, 74-77)

Ray Moore (1978-79, 81-82, 86-87)

Steve Jones (1980)

Ken Bruce (1988-2022)

Scott Mills (2023-)

Rylan Clark-Neal (2023-)

Semi-Final commentators:

Patrick O'Connell (TV: 2004-10, Radio: 2023)

Sarah Cawood (2007, 09-10)

Caroline Flack (2008)

Scott Mills (2011-)

Sara Cox (2011-12, 21)

Ana Matronic (2013)

Laura Whitmore (2014)

Mel Giedroyc (2015-17)

Rylan Clark-Neal (2018-19, 22-)

Richie Anderson (Radio: 2024)

Broadcast

BBC Television Service, 24 May 1956 to present

BBC Light Programme, 1957 to 6 April 1968

BBC Radio 1 (also on Radio 2), 29 March 1969 and 21 March 1970

BBC Radio 2, 3 April 1971 to 24 April 1982, 3 May 1986 to present

BBC Three, 12 May 2004 to 21 May 2015 (Semi-Finals)

BBC Four, 10 May 2016 to 20 May 2021 (Semi-Finals)

BBC Three, 10 to 12 May 2022 (Semi-Finals)

Synopsis

WHAT is the Eurovision Song Contest? Or, more exactly, WHY is the Eurovision Song Contest?

I'll tell you why. Desperation. Dodgy haircuts and clothes. Bitchiness. Voting alliances. Forget Survivor and Big Brother, the Eurovision Song Contest is THE original reality show, and its annual audience of 120m people makes it at least twice as big as the US Survivor ever was. Not bad for something that's been going over 60 years.

The early years

The ESC was borne out of the San Remo musical festival in the 1950s and its intention was to bring the countries of Europe closer together, a little bit like the other EBU (European Broadcasting Union) innovation Jeux Sans Frontieres. Little did they know that the Eurovision was the one big reason why European integration just wouldn't work.

The Eurovision Song Contest, the self-proclaimed "Greatest Gameshow on Earth" is an international institution. The contest was first staged in Switzerland in 1956, and the UK has participated every year except 1956 and 1958. Every year on a Saturday in May, representatives from many countries in Europe (and Israel) all congregate somewhere to sing their hearts out and decide which was the best song. The song that gets the most votes wins, the writers and performers win some tatty gold medallions and the real prize is that the winning nation gets the honour to host the following contest next year.

Preparations for the British attack usually began in February with A Song for Europe. Once relegated to Sunday mid-afternoon, latterly on Saturday prime-time, all the finalists on the shortlist (chosen by a panel of experts) do their song on the telly, which is then put to a telephone vote to decide which is the most popular. This becomes the song that will represent us in the forthcoming international contest.

So, come the middle of May, twenty or so representatives from the countries competing descend upon some stadium or theatre in Europe, all with the hope of taking home the honours.

Cliff Richard, who controversially came second with "Congratulations" despite being heavily tipped to win

Cliff Richard, who controversially came second with "Congratulations" despite being heavily tipped to winEach grand show has its own distinctive style depending on where it's being held each year. The hosts always speak in English and French with some usage of other languages too. After the opening spiel we get on to the songs. Before each song, there's normally a so-called "postcard" - a little piece of PR film saying "look how great your host country is!" which seem to have some effort put into them and yet make no sense whatsoever. Look! There's a man fishing (connotation: Look! We might be a modern country, but we still do traditional stuff), but he's quite obviously staring at that castle over there. Zooming into the castle (connotation: Look! We have old buildings!), there's a bloke using a big computer (connotation: look how technologically advanced we are! Compare that to our traditional methods!) then he'll makes some whizzy lines jump out of the screen which will whizz round and form pictures of the members of the band about to perform. Zoom out of the band to find out that the band were in fact in the fisherman's eye. Continue zooming out to see the fisherman. The fisherman catches something - it's the flag of the next country up! Marvellous. Alright, so we made that up, but it's not too far from the truth.

"We haff vays ov making you watch"

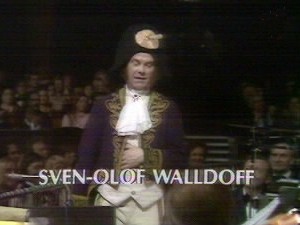

"We haff vays ov making you watch"Another highlight is the introduction of the conductors for the country about to perform, each one trying to outdo the other one in the nattiness of their evening attire.

If you think this is ridiculous, see what he wore after the operation

If you think this is ridiculous, see what he wore after the operationSo then, the songs - and what an eclectic lot they are. This is where we learn about the cultural differences between our partners. Failing that, we'll just laugh at them instead for being so bad. How many Eurovision entries of this era can anybody remember off the top of your head? Well Waterloo, of course, by the wondrous ABBA, Congratulations by ol' Cliff. Perhaps Makin' Your Mind Up, any song with La in the title (including the magnificent La La La). Ding A Dong was in ironic vogue for a while, erm...

Some ridiculously-attired people who later won the competition

Some ridiculously-attired people who later won the competitionThe one thing you can guarantee from the early years of Eurovision is that at least 80% of the songs will be utter rubbish. However, they might be saved if perhaps they're wearing "interesting" clothes, have "interesting" haircuts or dance "questionably", er, we mean "interestingly".

Admit it, you can't take this too seriously

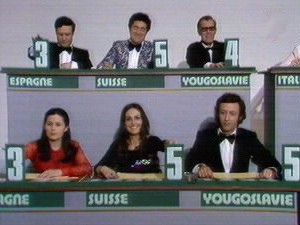

Admit it, you can't take this too seriouslyAfter all the songs have been performed we get a little break and each country would have a jury panel of people that were picked from whichever industry they're from and would rate down all the participating entries on a ranking list from last to first to each country, all while some sixth form musical act entertain in the background.

"No, this isn't the number for Domino's Pizza"

"No, this isn't the number for Domino's Pizza"When that's over, the important and interesting bit begins - the point giving. This is always very exciting because with the advent of computer technology you never know what the score board is going to look like or do until it comes on. Classic. Well it excites us, anyway.

The scores on the doors

The scores on the doorsEach country, in order of performance, is called up through a telephone line and say to the whole of Europe "Hello, London calling and here are the results of the United Kingdom jury." Although it seems customary for each country to say something along the lines of "We just want to thank you for putting on an excellent show tonight", which was very nice first time but ten years later and with every country doing it becomes very tedious.

Each country awards ten other countries points depending on how many votes each song got in their country. Since 1975, they've done it so the tenth most popular gets 1 point (it is customary for the hosts of the show to repeat everything in English and French), 9th two points... all the way up to 3rd which gets 8, 2nd which gets 10 and the most popular song which gets a whopping 12 points. Repeat with all the other countries, including Cyprus which makes us laugh because it sounds a bit like "sheep" when they say it in French.

From 1971 to 1973, each country representative gave up to 5 points per song via the set of Blankety Blank

From 1971 to 1973, each country representative gave up to 5 points per song via the set of Blankety BlankWhoever has the most points after every country has given their results is the illustrious winner and can be crowned Champions of Europe, or something. So the best song always wins, right? Well, let's look at the two other parameters that might affect the result.

1) Taste. Something that sounds good to us might not sound very good to the average Scandinavian. Middle of the road songs tend to win.

2) Bloc Voting. Oh yes, don't deny it doesn't exist, this is one of the humorous mainstays of Eurovision every year. The Nordic countries often vote for each other because not only are they neighbours, they also share languages, culture and music markets. Ditto Greece and Cyprus, the juries always give 12 points every year. Even if the song is very, very bad.

So every year it purports to be a song contest, instead it tends to be a needle match. Many countries take it incredibly seriously. And this is what makes it incredibly entertaining.

Nope, no idea who this is

Nope, no idea who this isEurovision, then. Not to everyone's taste but it is what you make of it. Watch it with some friends over and you'll have a ball. Watching it on your own is a bit tedious with the 2 hours of songs but still fun if you like it or don't watch. (Sage advice, no?) It's up to you really but it won't go away. No, it won't. It's here FOREVER... walks away, cackling evilly...

The format and voting changes through recent years

Because so many countries wanted to take part, they introduced a "relegation" system in 1993 where the bottom seven countries had to sit out a year to let other countries have a go. In 1994, the spokesperson during the voting got a technical upgrade where announcing the points through the telephone line was abolished and they were now seen on screen via satellite link up.

In 1996, the "relegation" system was replaced by a non-televised audio-only qualifying round and juries had to choose twenty-two out of the twenty-nine participants to go through to the actual final. This proved unpopular with the competing countries and the "relegation" system was brought back the following year in 1997, but this time the bottom seven countries that received the lowest "average" scores in the past five contests (participated or not) have to sit out in the next contest. The host country would always take part, even if their average wouldn't otherwise qualify.

Also in 1997, for the first time ever, the European public got to vote for their favourites! Televoting was trialled in five of the participating countries (the UK, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Sweden). The trial proved so successful that televoting became the rule for every country in 1998 (though everyone had the option to use a mixture of televote-and-jury in 2001 and 2002). Countries with poor telephone networks continued to use juries, and the jury would step in when a televote failed for whatever reason. No longer would the most jury-friendly song win, but victory would now go to the most popular song amongst the public.

Two fundamental changes were made in 1999. Out went the orchestra, the songs now being performed with backing tracks. And out went the rule dictating that a song had to be sung in the language, or one of the languages, of the country - it was now whatever language the country liked (in most cases English).

With France facing relegation in 2000, an exemption was introduced for the "Big Four" - the four broadcasters who made the biggest financial contributions to the EBU would automatically qualify to the contest. They were Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and - oh, look! - France.

In 2004, the "relegation" system was removed and a televised qualifying round called "semi-final" was introduced. The Big Four and the top ten from the year before went straight through to the contest proper (it's a bit like Going for Gold this, isn't it?) and drew lots on which running order position they'll be performing in the final. Everyone else had to compete for the final ten places. However, everyone watching had a say and televoting took place in the traditional way. The ten that qualify for the final are drawn into the vacant spots in the running order.

By 2008, with even more countries wanting to take part, a second semi-final was introduced in the week before the final. The Big Four and the host country remain pre-qualified for the final, but everyone else must take part in a semi-final, with the top ten songs from each semi-final progressing to the final. Each country only votes in the semi-final in which they are competing; an allocation draw in January determines which countries are in which semi-final, and where the Big Four and the host country will vote. From 2008 to 2012, the Big Four, host nation and ten countries that qualify from each semi-final drew lots during a press conference to determine which precise running order placing they'll be performing in the final, but since 2013, they were changed to which half of the final they'll be in with the producers deciding the running order in the early hours of Friday morning. The Big Four has been subject to inflation, and became a Big Five when Italy returned in 2011.

In all the semi-finals, the points scoring is kept a secret until after the main event on Saturday (to avoid bias we suspect) and the qualifying countries are put in envelopes (real or electronic) and announced at random. The countries that don't qualify for the main event still vote during the Saturday show. In 2004 and 2005, the spokesperson announced the points from 1 to 12 in the traditional way, but because there were a lot of results to read, it took over an hour to get all the points in. A new quicker way was introduced in 2006 where the points from 1 to 7 were displayed on screen and the spokesperson announced the 8, 10, and 12 points. From 2016, the spokesperson only announced the 12 points and lower marks from 1 to 10 were displayed on screen.

In 2009, there was a massive, though largely invisible, change in the scoring, whereby each country now has both an expert panel and a televote, which are combined 50/50 to give the country's final results. For the record, the expert panel has five members and they judge on the dress rehearsal rather than the final performance. We did read who was on the UK panel for 2009, but the only name we recognized was Zoe Martlew, one of the judges from Maestro.

In 2016, the 50/50 voting system was changed where now both the jury and televote scores have their own pool of points rather than one whole combined set. This voting system is inspired by the one Sweden have been using in their national selection Melodifestivalen since 1999.

A couple of changes in the voting system came in for the 2023 contest. Viewers in countries not taking part in the contest could vote online in both the Semi-Finals and the Grand Final - at a whopping €0.99 per vote. The second change is the semi-finals are now 100% televoting, juries were only used if a televote fails. The voting in the Grand Final remained unchanged.

Three more changes were made for the 2024 contest: the Big Five and the host nation would now perform their entries in full live during the semi-finals (in previous years we'd only seen short clips from the rehearsals of these songs), the draw for the Grand Final now has a third option called "producer's choice" which means that the host broadcaster gets free will on whichever half the qualifiers from the semi-finals will perform and the voting window in the Grand Final now opens before the first song was performed (returning to the format used in 2010 and 2011; voting in other years only began after all the songs had been performed).

Moving and grooving with the times

The Eurovision Song Contest sharpened its act at the start of the 2010s and became more relevant. Year by year, we saw fewer clichéd joke entries and more songs from many diverse genres. Winners like "Satellite" and "Euphoria" became cherished hits across the continent. It drew star presenters and well-known interval acts like Justin Timberlake. Some broadcasters found a niche - Moldova's entries were fun and upbeat, Dutch songs tended to be sombre and reflective.

The United Kingdom also found a niche, propping everybody up. Some claimed that this was the rest of Europe showing their prejudices against a country, but that's cobblers. The UK failed because its songs generally weren't good enough. The semi-finals weed out many of the weaker entries, so Saturday night is filled with tested successes - and whatever the Big Five send. The Eurovision scoring system finds a winner, and it exposes weak entries without mercy.

Eurovision is one of the few competitions where San Marino competes on the same level as Germany, one of the few places where powerful nations can be taken down a peg or two. The 2016 winner was "1944", a song about the forced removal of Tatars from Crimea, perhaps a reminder to Russia that historic crimes aren't forgotten. Ukraine won again in 2022, a clear message from the European public that Russia's contemporary crimes - waging war in Ukraine - are not forgiven.

As the contest approaches its platinum anniversary in 2026, the Eurovision Song Contest looked in better shape than ever. It had given us worldwide success "Arcade", and followed it up with champion band Måneskin. The show's place was assured - whether as a cultural icon, or as an excuse for Europe to sing karaoke and get roaringly drunk together.

Commentating for Auntie

Ever since the contest began in 1956, each broadcaster would have someone in the booth to guide the viewers through the contest's proceedings in their own language. Many commentators come back year after year - David Jacobs covered most of the 1960s for the BBC, and radio coverage was headed for many years by Ken Bruce.

Terry Wogan, who had been commentating for television (and briefly radio) audiences since the early seventies, understood that Eurovision is so good, but only because it's so bad. He gave an alcohol-inspired dry and sarcastic commentary, which became an integral part of the BBC's night. "Every year you think it can't get any worse..." but oh, it did. Who needs real names when you can just call the hosts "Dr Death and Little Bo Peep" and let them get on with it? A man who would say after one song "that could win it," and after the next "I would comment but I was too distracted" after a woman in a tight suit was singing? And he got just as flabbergasted every time a Balkan ballad gets top marks from Bosnia-Herzegovina. Remarkable.

Wogan stepped down from the commentary booth after the 2008 contest. This was probably for the best. Eurovision had evolved with bigger venues and a younger crowd; the contest was now a pop concert wearing t-shirts and jeans, Wogan's commentary was an anachronism from an evening in tuxedos. The BBC grabbed the next available Irishman, who just happened to be Graham Norton. Norton made an assured debut, and slowly eased himself away from the inevitable Wogan comparisons - he's sharp but never nasty. Crucially, Norton knows when to shut up so that we can actually hear the songs properly, something that Wogan never mastered.

Spin-offs

The Eurovision Song Contest spread its wings. The Junior Eurovision Song Contest was established in 2003, and has sent a number of competitors to the Senior contest. Eurovision Asia was promised on a number of occasions but never arrived. The American Song Contest ran in 2022, with the US states and territories competing against each other.

Key moments

Too many to mention, but one of the best has to be the chaos of the 1969 finals. When the votes had been added up, it was discovered that four countries had received 18 votes. There were no contingency plans in the EBU rulebook to cover a tie, so the hostess had no option but to declare a four-way tie. All four countries performed their winning songs at the end of the night.

Inventor

Accredited to Frenchman Marcel Baison, who set up the Italian "San Remo Song" Festival (still going) which gave the idea of the Eurovision.

Theme music

Te Deum, composed by Marc-Antoine Charpentier.

Trivia

The UK has come second in the competition a staggering 16 times. Its five victories were performed by Sandie Shaw (Puppet on a String, 1967), Lulu (Boom Bang a Bang, 1969), Brotherhood Of Man (Save Your Kisses For Me, 1976), Bucks Fizz (Making Your Mind Up, 1981) and Katrina and the Waves (Love Shine a Light, 1997).

There's no restriction on the nationality of performers, which explains how Australian Gina G represented the UK with "Just a Little Bit" in 1996, and how Switzerland came to be represented in 1988 by Céline Dion from Canada.

The winner of the competition gets first refusal on hosting the contest the following year. In the case of repeat winners (e.g. Ireland) or poorer countries, sometimes the costs involved put a strain on the national broadcasters. The sitcom Father Ted had fun with this in a famous plotline in which Ireland deliberately send an awful song in order to avoid the cost of hosting the contest, but in real life, countries can and do turn down the opportunity to host the contest, electing for the honour to go instead to any offering broadcasters. For example after Monaco won in 1971, they declined as there wasn't a large enough hall in the principality, and since the French didn't want it, it was offered to the BBC, with the result that the 1972 contest was held in Edinburgh. Luxembourg also declined the honour in 1973, after winning for the second time in a row. It was again given to the BBC which hosted it in Brighton in 1974. The BBC was also tasked with holding the 2023 event, albeit with everyone involved keen to make it clear this was "on behalf of" 2022 winners Ukraine, who had wanted to host it themselves as an act of defiance against the Russian occupation, but were overruled by the EBU, citing the obvious practical concerns of holding a major international event in an actual warzone.

Italy stopped taking part in the ESC after 1993, claiming a "lack of interest" in the competition; an entry in 1997 only hardened the position of broadcaster RAI. Time marched on, opinions mellowed, and the country returned in 2011 with "Big Five" status, meaning they automatically qualify for the final. Luxembourg also stopped participating, despite having previously been one of the most successful countries: they were relegated following a poor performance in 1993, and wouldn't take part again for another thirty years; it was announced during the 2023 contest that they would be returning to compete in 2024.

Eurovision on Radio 1? That's how the BBC worked in '69 and '70: Radio 1 produced the late evening shows, such as the 10pm Eurovision Song Contest. The shows were simulcast on Radio 2's long wave and VHF transmitters.

For the record, the UK jurors for the 2009 contest were (and we only got the names and had to look up the rest ourselves, so apologies if we've got the wrong Paul Edwards, or whoever):

- Semi-final

- Deborah Chapman (author?)

- Paul Edwards (dean of the Royal College of Music)

- David Larkin (?)

- Anne Mannion (stage actress)

- Chris Stewart (musician, ex-Genesis)

- Final

- Paul Goodey (oboeist and tutor at the Royal Northern College of Music)

- Steve Allen (might be the LBC presenter, or might be the former Deaf School and Original Mirrors singer, or might be neither...)

- Zoe Martlew (composer, cellist and Maestro judge)

- Keith Hughes (perhaps the music historian involved in compiling various compilation CDs for Universal?)

- Jasmine Dotiwala (MTV producer and pop pundit)

From 2011 to 2015, the BBC selected the song and performer without consulting the public. The first three entrants were announced on early evening magazine programme The One Show. In 2014 and 2015, the BBC Red Button spent some of its small budget on a special show to announce the competitors. Eurovision Reveal (3 March 2014) and Our Song for Eurovision 2015 (7 March 2015) both featured a performance and an interview with Scott Mills. After a number of years where the song was unveiled on magazine programme The One Show, the 2024 entry was premiered on Eurovision 2024: Graham Meets Olly (1 March 2024).

To mark the contest's 60th anniversary in 2015, the EBU decided to invite Australia to compete as a one-off. The contest has a loyal following Down Under, having been broadcast by SBS for over 30 years. Former Australian Idol winner Guy Sebastian was chosen to represent Australia at the final in Vienna, singing self-penned song Tonight Again. It was announced that Australia would be able to defend their crown in 2016, in a European city of their choice, should they win. In the event, Sweden took home the honours, however Australia did finish in a respectable fifth place. As a result of positive feedback to Australia's participation, it was announced in November 2015 that the country would be invited to compete in the 2016 contest. However this time they would not be granted a pass to the final, and would have to take part in one of the semi-finals to secure their place in the final. They've been a regular competitor ever since.

No contest was held in 2020 as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Rylan Clark-Neal had expected to co-host the semi-finals in 2021, but was taken ill a few days before they started. He was replaced on the panel by Sara Cox.

Web links

Pictures

The pine-needle style logo for the Eurovision.

The pine-needle style logo for the Eurovision.See also

Junior Eurovision Song Contest

Weaver's Week coverage:

- 2003: Eurovision Song Contest

- 2004: Qualifier | Final | Final analysis

- 2005: Qualifier | Final

- 2006: Semi-final | Final | Voting analysis

- 2007: Semi-final | Final | Voting analysis

- 2008: Voting predictions | Semi-final | Final

- 2009: Semi-final | Final

- 2010: Semi-final | Final

- 2011: Semi-final | Final

- 2012: Semi-final | Final

- 2013: Semi-final | Final

- 2014: Semi-final | Final

- 2015: Semi-final | Final | Voting analysis

- 2016: Semi-final | Final

- 2017: Semi-final | Final

- 2018: Semi-final | Final

- 2019: Semi-final | Final

- 2020: Europe Shine a Light and Come Together

- 2021: Semi-final | Final

- 2022: Semi-final | Final

- 2023: Liverpool report and semi-final | Final

- 2024: Semi-final | Final